How Rivian sparked a surprising new divide in Georgia’s gov race

RUTLEDGE — The tidy lawns of this east Georgia town are lined with signs protesting Rivian’s plans to build a $5 billion electric-vehicle plant here. But the real show of opposition was on display in the main park.

Before a crowd of residents waving anti-Rivian placards, former U.S. Sen. David Perdue promised Tuesday to combat the largest development project in Georgia history if he defeats Gov. Brian Kemp — and said he would have killed the deal outright if it didn’t have local buy-in.

“I’m here to shine light on the fight this community is in right now,” he said. “You guys want to be heard, but your governor is refusing to listen. I’m here to tell you: I hear you, I see you, and I’m standing with you right now in this fight.”

Not so long ago, it would have been unfathomable for a high-ranking Republican running for statewide office to find fault with an auto manufacturing project that promises to generate thousands of high-paying jobs.

Georgia Republicans have long framed themselves as a pro-business party eager to recruit new development. And state officials from both parties have practically pleaded for a new automobile factory after a string of near misses and stinging defeats.

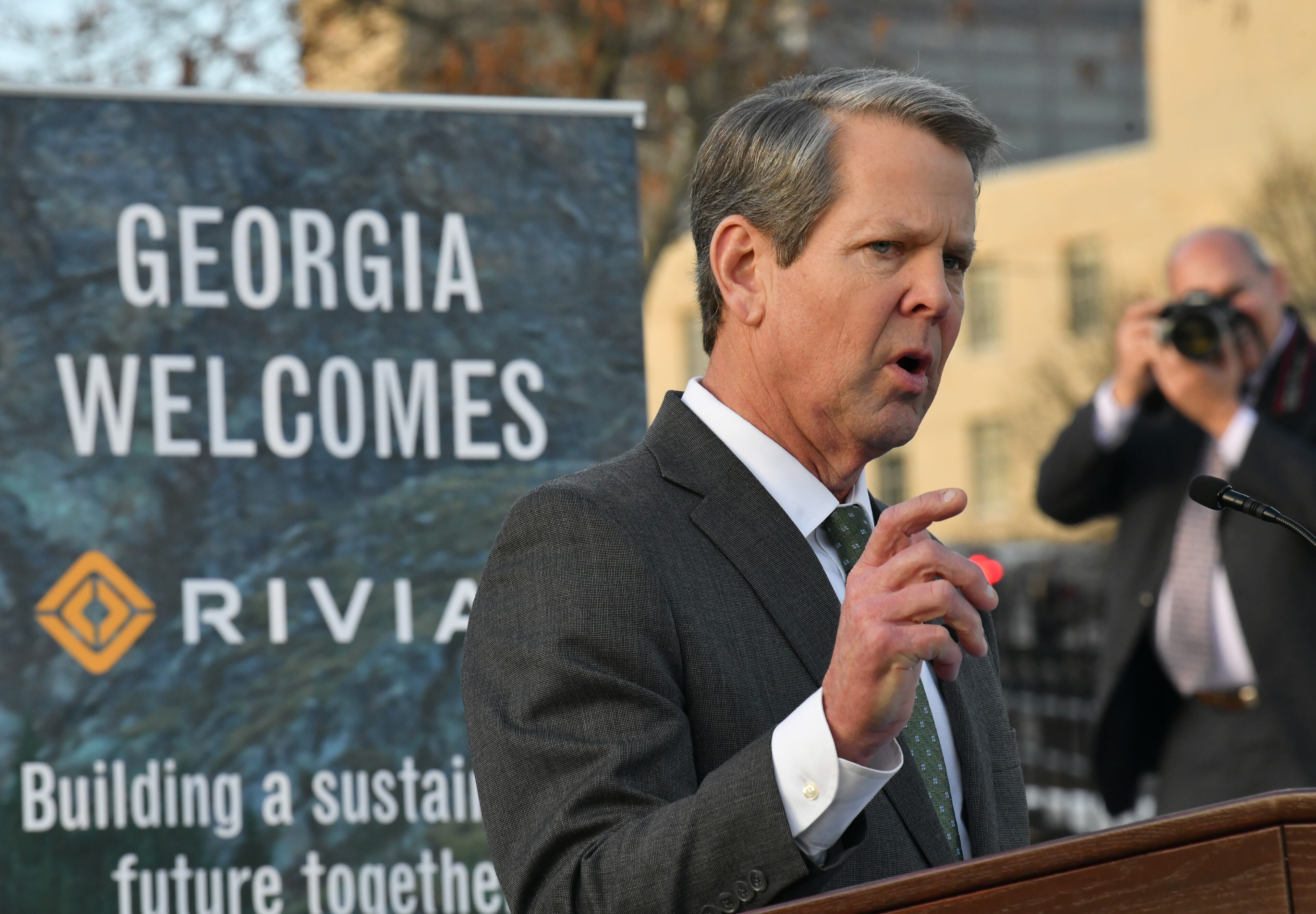

But this election year has brought new scrutiny to Kemp’s crowning economic achievement, as some Republicans tap into the concerns of residents worried about planting such a large industrial development in this rural area about 45 miles east of Atlanta.

Already, a grassroots anti-Rivian campaign lists Kemp and “everybody else who has aided and abetted this outrageous back-door deal” as enemies. Republicans running in the 10th Congressional District have rallied voters for weeks to stand against the project.

Some residents have complained they were kept in the dark as authorities negotiated in secret with Rivian, which plans to employ about 7,500 people on a roughly 2,000-acre site. Others have vented at the public dollars used to subsidize the project.

John Strickland, a retired law enforcement officer who leads the local anti-Rivian effort, told the crowd he’s tired of “fence-sitting” politicians. He’s helped raise about $250,000 so far to contest the project.

“We don’t want this assembly plant here and we’re not going to let it destroy our community,” he said. “Gov. Kemp, you’re on a crossroads: You can either stay on the road you’re on or change course and support rural Georgia and our farmers and stop this.”

‘Not a partisan issue’

Perdue’s opposition brings an even sharper edge to the battle against the auto manufacturer — and to his Donald Trump-backed primary challenge against Kemp.

As a former Fortune 500 chief who rose to the top ranks of Reebok, Sara Lee and Dollar General, Perdue is well versed in the ways that businesses bargain with governments for tax breaks and public incentives.

“It doesn’t have to happen this way. You’re buying these jobs instead of growing them organically,” said Perdue, who added that he’d “not let this deal go if I had a way.”

“I would have fought this until we had local buy-in of the local people here — not just the people who are politically connected, but everybody who bears interest in the deal.”

Kemp’s allies expressed shock that Perdue slammed an economic development triumph they believe he should have celebrated.

Chris Riley was involved in dozens of economic development projects throughout the past decade as then-Gov. Nathan Deal’s top aide. He said Perdue knows better than most how lucrative incentives and private negotiations are key to competing for projects.

“It’s not a partisan issue. It’s a staple of economic development programs in all 50 states,” Riley said. “I find this all odd. Perdue served on the Ports Authority. He was a corporate CEO. Wasn’t he for the use of incentives before he was against it?”

It’s not yet clear exactly what perks Kemp’s administration offered Rivian, and an aide to the governor declined to comment Tuesday on the extent of the package. The company’s executives recently told residents that negotiations are still ongoing.

But key details have emerged involving what’s expected to be the largest incentive package in state history.

The governor’s budget plan includes $125 million for land and training costs for Rivian, and state law allows for hundreds of millions of dollars in tax incentives tied to new jobs in the deal.

A legislative measure that would let the company sell its vehicles directly to Georgians is pending. Infrastructure improvements are in the works. And new high school and tech college courses are under development.

But Perdue’s opposition is also rooted in sheer politics. He made that clear when he pledged to “stop Soros-funded Rivian and protect rural Georgia.”

“Kemp didn’t just sell us out, but he sold out to somebody who doesn’t have our best interest at heart,” he told residents, many of whom were clad in bright-red shirts in protest of the plant.

That’s a reference to the recent disclosure that billionaire investor George Soros, a Democratic mega-donor vilified by conservatives, bought a $1 billion-plus stake in the electric-vehicle startup.

Rivian’s other early investors include Amazon, the Ford Motor Co. and T. Rowe Price. Cox Enterprises, owner of The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, owns a 4.7% stake in Rivian. Sandy Schwartz, a Cox executive who oversees the AJC, is on Rivian’s board of directors and holds stock personally. He does not take part in the AJC’s coverage of Rivian.

Kemp campaign spokesman Cody Hall said Perdue is pandering to “gain a couple more votes.” He referred to a 2014 interview with Perdue saying he was “proud” of shifting manufacturing and jobs to cheaper markets.

“Folks really shouldn’t be surprised that David Perdue is opposed to 7,500 jobs coming to Georgia,” Hall said, “because he built his entire career in business sending these kinds of jobs overseas.”

’Time to stand up’

It’s exceedingly rare for top candidates for statewide office to criticize major jobs deals, particularly after years of Republican boasts that Georgia is the “No. 1 state in the nation to do business.”

When Kemp announced the Rivian development in December, for instance, Democrat Stacey Abrams praised the company’s ties to organized labor as she welcomed the jobs.

And Perdue’s first cousin, Sonny Perdue, relied on a bounty of incentives when he was governor to persuade Kia Motors to build a plant in West Point in 2006.

The Kia and Rivian developments are rare triumphs for Georgia in the auto sector. Over the past 40 years, Asian and European carmakers repeatedly bypassed Georgia for neighboring states. Just a few years ago, Georgia lost out to South Carolina in a hunt for a Volvo plant.

In an interview in December, Kemp called the Rivian plant a “generational, transformational” deal. And state leaders predicted it would boost the state’s burgeoning reputation as a magnet for the electric-vehicle industry.

Now, Kemp administration officials are reassessing their strategy. The state recently stepped in to take control of the Rivian site, a move that could potentially ease the passage of crucial zoning changes.

Rivian plans to hold more public meetings to forge better relations with community.

Some residents say it’s too late for bridge-building.

“There’s nothing Rivian can do. There’s nothing that will be acceptable,” said Tonya Bechtler, who lives a few miles from where the plant would be built. “We want things just the way they were. We are tired and it’s time to stand up.”