Georgia Democrats are heading to Chicago giddy with the belief that with Kamala Harris now their presidential nominee, the state could once again play an important role in sending a Democrat to the White House. They’ll join Democrats from across the country who feel a sense of unity that was fraying when polls suggested Donald Trump appeared to be on track to beat an aging President Joe Biden.

My hometown of Chicago has hosted more national political conventions than any other U.S. city. And the consequences of conventions held there have often played a role in determining the party that won the White House. There’s no better example of that than the chaotic 1968 Democratic National Convention.

Over four days that August, events in the convention hall spiraled out of control in a manner similar to the confrontations that pitted anti-war demonstrators against the police on the streets of Chicago.

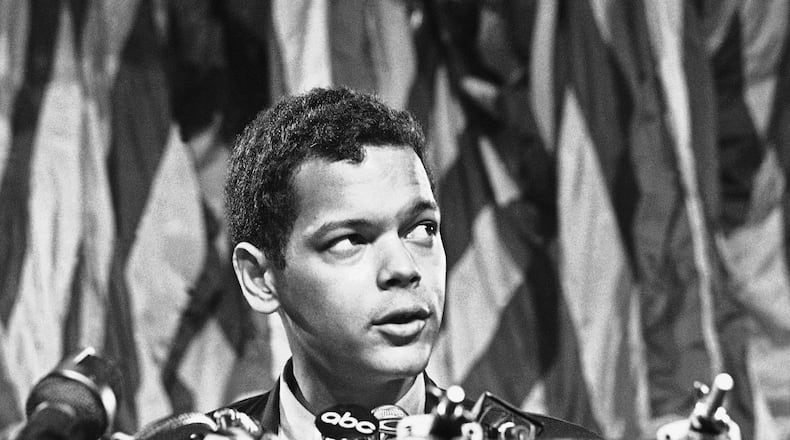

And in the middle of much of the tumult stood 28-year-old Julian Bond, a Black Democratic Georgia legislator whose political star was just beginning to rise, and who, before the convention came to an end, would be a surprise nominee for vice president.

Credit: AP

Credit: AP

By the time Bond arrived in Chicago during that hot summer, the Democratic coalition of Northern liberals and Southern conservatives who had elected John F. Kennedy in 1960 and Lyndon Johnson in 1964 was coming unraveled. The segregationist wing of the party was still fuming at Johnson for signing the Voting Right Act of 1965. As if that weren’t enough, fierce opposition to the Vietnam War led many liberal Democrats, such as Bond, to back the candidacy of Eugene McCarthy and to oppose the party’s presumptive nominee, Vice President Humbert Humphrey, who, after Johnson withdrew from the race, carried the baggage of the war into the convention.

Bond was co-chair of a group of Georgia civil rights and anti-war activists who filed a challenge with the credentials committee, making the case that they should replace the state’s regular delegation, which was led by Gov. Lester Maddox. Maddox had used his powerful influence to pack the delegation with like-minded segregationist Georgians. (Although he wisely included several African American delegates, including Atlanta state Sen. Leroy Johnson, the first Black Georgian elected to the General Assembly since Reconstruction.)

When the credentials committee failed to extract a compromise between the two groups, the issue went before the entire convention, adding to the discord of an already tumultuous week and exposing to the country how Democrats were grappling with the growing influence of African Americans within the party.

In the end, the convention approved a Solomonic solution — half of each Georgia group would be recognized as official delegates. Julian Bond and his allies had won an unexpected victory, and it thrust him into the national spotlight.

Credit: AP

Credit: AP

Bond’s sudden fame was just what members of the Wisconsin delegation were looking for. They were a group of passionate anti-war and pro-McCarthy delegates. And they were outraged by the way Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley had turned his Police Department loose to beat protesters in the streets and parks of the city.

And so, on the third night of the convention, as the roll call of the states was underway to formalize Humphrey’s selection of Ed Muskie to be his running mate, Wisconsin delegate Ted Warshafsky walked to a microphone, and asked to be recognized to place a different name in nomination for vice president:

“Mr. Chairman, we of Wisconsin as Democrats who are interested not only in what the party is but what it will become ... if it will truly make the American dream a reality not only for affluent delegates, but for the young people who march in the park looking for quality in life. So I will say as simply and as sincerely on behalf of my delegation that we offer in nomination the wave of the future ... Julian Bond.”

CBS’ dogged correspondent Dan Rather immediately raced to find Bond on the floor and interviewed him on live television:

Rather: Mr. Bond, how old are you?

Bond: I’m 28.

Rather: And how old does the vice president legally have to be?

Bond: 35, I believe.

Rather: So it isn’t likely that you’re going to be a serious nominee.

Bond: No, no. This convention might mandate that Congress or request that Congress change the age by election time and maybe I might make it.

Rather: Well, you’re saying that tongue in cheek. ...

But Bond was serious. While he knew he didn’t meet the age requirement, he hoped that by having his name placed in nomination he’d be able to address the convention on the issues that he told Rather “weren’t being discussed ... poverty, racism, war.”

That speech was not to be. Before another Wisconsin delegate could second Bond’s nomination, the floor microphone stationed in the delegation was turned off. Bond’s interview with Rather would be his moment to address his concerns about what he believed the convention should be discussing.

Most political analysts agree that Humphrey struggled to recover from the chaotic Chicago convention. He lost the 1968 election to Richard Nixon in an Electoral College landslide.

Many of the Maddox Georgia delegates to the convention voted for independent segregationist candidate George Wallace in the general election. And Wallace won a plurality of Georgia votes that year, beating both Humphrey and Nixon.

In the years following the Chicago convention, Bond went on to serve for two decades in the General Assembly. He was the first president of the Southern Poverty Law Center and became chairman of the NAACP. But in 1986 he lost a bitterly fought race for Congress against his longtime close friend and fellow civil rights activist John Lewis. It was decades before the two came together to repair their broken friendship.

Bond died at age 75 in 2015. But Chicago will be one of his legacies. As disastrous as the 1968 convention proved to be, his role in the delegate challenge helped pave the way for the multiracial coalition of Democrats who will gather next week in Chicago with renewed hopes of victory in November.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured