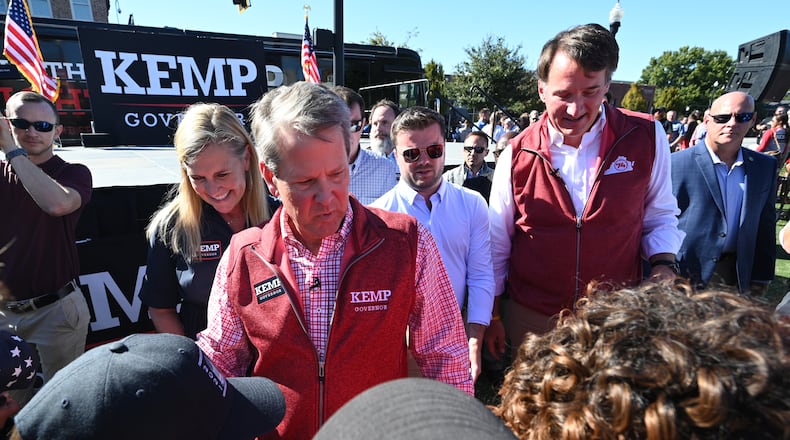

As Glenn Youngkin prepared to wrap up a campaign appearance with Gov. Brian Kemp, he paused to wrap his Georgia counterpart in something else: a red vest modeled after the Virginia governor’s trademark outfit.

That’s not all that Kemp has taken from Youngkin. Ever since the lanky Virginian scored an upset victory last year, Kemp has tried to channel the same electoral forces that Youngkin used to drive worried parents frustrated by pandemic-related school policies to the polls.

To highlight that strategy, Kemp invited Youngkin to a crowded rally in Alpharetta in one of his first campaign forays in the suburbs this cycle. The Virginia governor told hundreds of cheering supporters that they had avoided the political strife that led to a GOP revolt in his state by voting Republican in 2018.

“You didn’t have that because you had Brian Kemp,” Youngkin said. “We made a big statement for change. And we made it loudly. Now it’s your turn to make a big Georgia statement that we’re going to give Brian Kemp four more years.”

Kemp’s narrow victory in 2018 was fueled by a strategy to wring out every conservative vote he could by energizing Donald Trump backers who typically skipped midterm elections.

But even before the governor’s falling-out with Trump, he and his advisers acknowledged the same formula wouldn’t work in 2022. An ongoing population drain in the state’s agricultural heartland and an influx of residents in growing areas around Atlanta forced him to seek new paths to victory.

So far, Kemp has focused much of his campaign’s energy on deep-red rural areas where he’s trying to drive up the score against Democrat Stacey Abrams. But while he hardly stumped in the suburbs four years ago, the stop Tuesday in Alpharetta marked an attempt to expand his electoral map.

Just as Abrams hopes to cut Republican margins in rural areas, the governor aims to compete in territory that Joe Biden and Abrams carried by broad majorities in the past two election cycles. And even a slight shift could pay dividends for Kemp.

Credit: HYOSUB SHIN / AJC

Credit: HYOSUB SHIN / AJC

“The state is so competitive that you’re trying to peel off anyone you can, so why not go into areas where you can pick off some voters?” said Karen Owen, a University of West Georgia political scientist.

“The governor is trying to talk to once-reliably Republican voters who didn’t align with Trump,” Owen said. “Now he’s asking whether they’ve really flipped to the Democrats or if they’re ready to go back home to the Republican Party.”

‘Put it right’

Even amid a tough political climate for Democrats, Republicans still face formidable struggles in the suburbs.

After flipping Democratic in 2016 for the first time in decades, Cobb, Gwinnett and Henry counties now form a cornerstone of the state party’s coalition. And in 2020, Biden outdid Hillary Clinton in many suburban precincts, helping him overcome Trump’s gains in rural areas that turned a deeper hue of red.

Biden won Gwinnett County by 18 percentage points — tripling Clinton’s 6-point edge in 2016. Biden bested Clinton’s performance in 2016 by five times in Henry County, carrying it by about 20 points.

And Democrats also improved on their party’s performance in Cobb, DeKalb and Fulton counties — along with exurbs in Cherokee, Douglas, Fayette and Forsyth counties on the edges of the metro area.

Some activists predict an ugly November wake-up call for Republicans. Jeanna Trugman of Roswell said the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe v. Wade, which allowed Georgia’s anti-abortion law to take effect, galvanized suburban women in ways that don’t surface in public polls.

Credit: Steve Schaefer

Credit: Steve Schaefer

“I’m canvassing every single day for Democrats,” she said. “There are a lot of us out here — and we are working.”

Abrams has centered her campaign on calls to expand Medicaid, tap Georgia’s $6 billion-plus surplus on “generational” proposals, and oppose Republican-backed gun expansions and abortion restrictions she said will undercut the state’s economic growth.

“It’s costing us jobs. It’s costing us opportunity, and it is the precursor to how we lose our rights in the state of Georgia,” she said at a recent stop in Forsyth County. “I know that a man had to break the promise. It’s going to take a woman to put it right.”

‘A lot like Georgia’

Kemp and his aides can afford to take a different approach than they did in 2018, when he promoted provocative conservative policies on immigration, guns and abortion with a base-first strategy that helped him outperform Trump by several percentage points in parts of rural Georgia.

While Kemp isn’t running away from anti-abortion policies that could hurt him in more moderate areas, he’s far more likely to remind voters of his decision to aggressively reopen the state’s economy during the early months of the coronavirus pandemic or use surplus funds to finance tax rebates.

“If you look at how far Brian Kemp ran to the right four years ago, it cost him communities like Alpharetta,” said Ben Burnett, a former Alpharetta councilman and GOP commentator. “But Republicans can now effectively compete here with the right message.”

Credit: HYOSUB SHIN / AJC

Credit: HYOSUB SHIN / AJC

And with solid leads in most public polls — he led Abrams in the most recent Atlanta Journal-Constitution poll with 50% to her 42% — Kemp is confident he can compete in new territory.

Youngkin’s strategy in Virginia has emboldened that approach. Kemp began sharpening his education platform in November, shortly after Youngkin defeated a former Democratic governor by appealing to both Trump supporters and more moderate suburbanites with a focus on classroom issues.

The centerpiece of the package Kemp signed into law earlier this year seeks to direct how public school educators teach students about race and “divisive concepts,” along with another that blocked transgender students from playing on sports teams that don’t match the gender on their birth certificate.

Other new laws make it easier for parents to seek to remove books considered “obscene” or inappropriate from public school classrooms and coursework, and allow parents to opt their children out of mask mandates.

“Parents had a lot of concerns. Parents are worried about their kids. They’re worried about the economy and wanting people to get back to work. That’s what he stayed focused on,” Kemp said of Youngkin’s formula. “And, look, it’s what we’ve been focused on here in Georgia.”

Credit: HYOSUB SHIN / AJC

Credit: HYOSUB SHIN / AJC

Concerns over education policy is a top factor for Suzanne Cassada, an Alpharetta voter who blamed Democrats for the spate of coronavirus restrictions that led many schools to resort to virtual learning for months. She said the pandemic has made the suburbs far more fertile ground for Republicans.

“There’s a lot more awareness now,” she said. “The Democrats have proven themselves, and women are moving away from them — especially if they’re parents. They don’t want what’s happened in the schools to happen again.”

Youngkin also had a score-settling reason to visit Georgia. Abrams campaigned for Democrat Terry McAuliffe last year in the closing days of the Virginia race for governor, praising the former governor’s voting rights record.

Youngkin chuckled as he told the crowd that Abrams warned Virginia voters that their state would “become more like Georgia” if a Republican was elected.

“I’m proud to say that our economy is growing. Our kids are back in school. We’re returning taxpayers’ money to them,” he said, his voice rising as a wide grin spread across his face.

“I am proud to say that, yeah, we’re a lot like Georgia.”

Credit: HYOSUB SHIN / AJC

Credit: HYOSUB SHIN / AJC

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured