Georgia’s female legislators still face glass ceiling

State Rep. Sally Harrell had recently given birth to her first child in January 2000 when she received a phone call from one of the most powerful men in Georgia politics.

Then-speaker Tom Murphy had heard that the first-term lawmaker was planning to bring her newborn son — who, at 3 weeks old, was too young to be accepted into day care — to the impending legislative session. The news had ignited a brushfire among some of the General Assembly’s more traditional members, who were taken aback by the idea of a baby in the House chamber, not to mention the thought of one who was still nursing.

“I’ve been here 27 years, and I’ve never had this problem,” Murphy told Harrell, who now represents a Dunwoody-based state Senate district.

It’s hard to imagine a similar conversation today. A century after the 19th Amendment was adopted, opening the door for women to vote and hold public office, the General Assembly boasts a record number of female legislators, including several who are young mothers. The state has the highest percentage of women lawmakers of any Legislature in the South.

But the unprecedented numbers obscure a glaring fact: Women have yet to hold any of the top positions under the Gold Dome.

With few exceptions, the top decision-makers in all three branches of state government are men. None of the General Assembly’s most powerful committees, the ones that control the state’s purse strings and are closest to party leadership, has ever been run by a woman. There has never been a female governor or lieutenant governor, nor a woman speaker or senate president pro tempore.

Part of the discrepancy stems from recruitment. The women who are running and being elected to the statehouse are mostly Democrats, but the Legislature is currently controlled by Republicans, a party that says it eschews identity politics.

The dearth of powerful women has vast implications for the kinds of issues that come before the statehouse and how they’re approached.

Twisting arms

Women currently make up 30% of the General Assembly, but that wasn’t the case when Sen. Nan Orrock, D-Atlanta, arrived at the statehouse as a representative in 1987. Only 1 in 10 legislators was female, and women were such an afterthought that there wasn’t even a women’s restroom on the Senate side of the Capitol.

If women lawmakers had lunch together, Orrock said, it “was viewed as threatening and frowned upon” by the male Democratic leaders who ruled the statehouse with an iron fist. Back then, it was all but impossible for women to break into the institution’s inner circles.

Still, as a former community activist, Orrock convinced many of her Democratic and Republican female colleagues to create the Georgia Legislative Women’s Caucus. The group’s purpose was to find areas of agreement on matters impacting women and families and to pursue them legislatively even if male colleagues weren’t interested.

The caucus’ first order of business was securing federal funding for childcare programs. Then came a slew of bills on an issue that once bridged the political divide: health care.

Early victories included measures mandating minimum hospital stays for women after giving birth and requiring health insurers to cover tests ranging from mammograms to cervical cancer screenings.

A bipartisan group of female representatives would line the walls of the mostly male Senate chamber as they voted. It was a strategy the group relied on again and again.

“We went over there and twisted arms and looked in their eyes,” said Orrock, who was a floor leader for Gov. Zell Miller.

In 2005, the caucus fought a measure that would have stripped many of those same mandates from the law and managed to save key parts of the health initiatives the bipartisan group had fought so hard for.

The group remained a force for a while, but eventually Republican legislators left. Issues like health care were becoming increasingly politicized, especially after the passage of the Affordable Care Act. A polarized electorate demanded even greater party loyalty.

Sen. Renee Unterman, R-Buford, joined the caucus after being elected to the House in 1999, but has since left the group. She said she no longer sees a need for it “because we’ve been integrated and are doing better.”

“But, back in the day, we did have to fight,” she said.

Dwindling GOP women

The transition of the Women’s Caucus into a de facto single-party group made it even harder for rank-and-file female legislators to wield influence as a bloc.

Women have run for office in record numbers in Georgia in 2018 and 2020, but mostly as Democrats. Women make up the majority of the Democratic caucus in the General Assembly, but men are in the top party positions in both the House and Senate and the minority has limited powers.

At the same time, the number of elected female Republicans has flattened over the last decade.

When Unterman retires at the end of the year, there could be only one GOP woman serving in the Georgia Senate. One female Republican incumbent is running for reelection and another is seeking to fill the seat of a retiring GOP senator.

Of the women serving in the House, 15 are Republicans and 42 are Democrats.

Some observers attribute the yawning gender gap to recruitment.

While Democrats have a bevy of established, deep-pocketed groups like Emily’s List and Georgia WIN List dedicated to recruiting and training female candidates, GOP women lack a similar network of outside support. The Republican Party hasn’t traditionally gone out of its way to recruit women or minorities for office, but that’s beginning to change.

The D.C.-based Republican State Leadership Committee announced plans earlier this year to aid three incumbent GOP women in the Georgia House and five challengers through its “Right Women, Right Now” initiative.

“Women are the majority in this country — they’re 54% of voters,” said President Austin Chambers, a Georgia native who previously worked on the campaigns of Gov. Brian Kemp and U.S. Sen. David Perdue. “If we want to be a majority party long-term, we better become a party of women.”

Lt. Gov. Geoff Duncan, who presides over the state Senate, said he’s made it a priority to use his independent fund Advance Georgia to seek out and support Republican candidates who are women and people of color.

His group is backing Sheila McNeil, a woman seeking to fill a vacant seat on the Georgia coast.

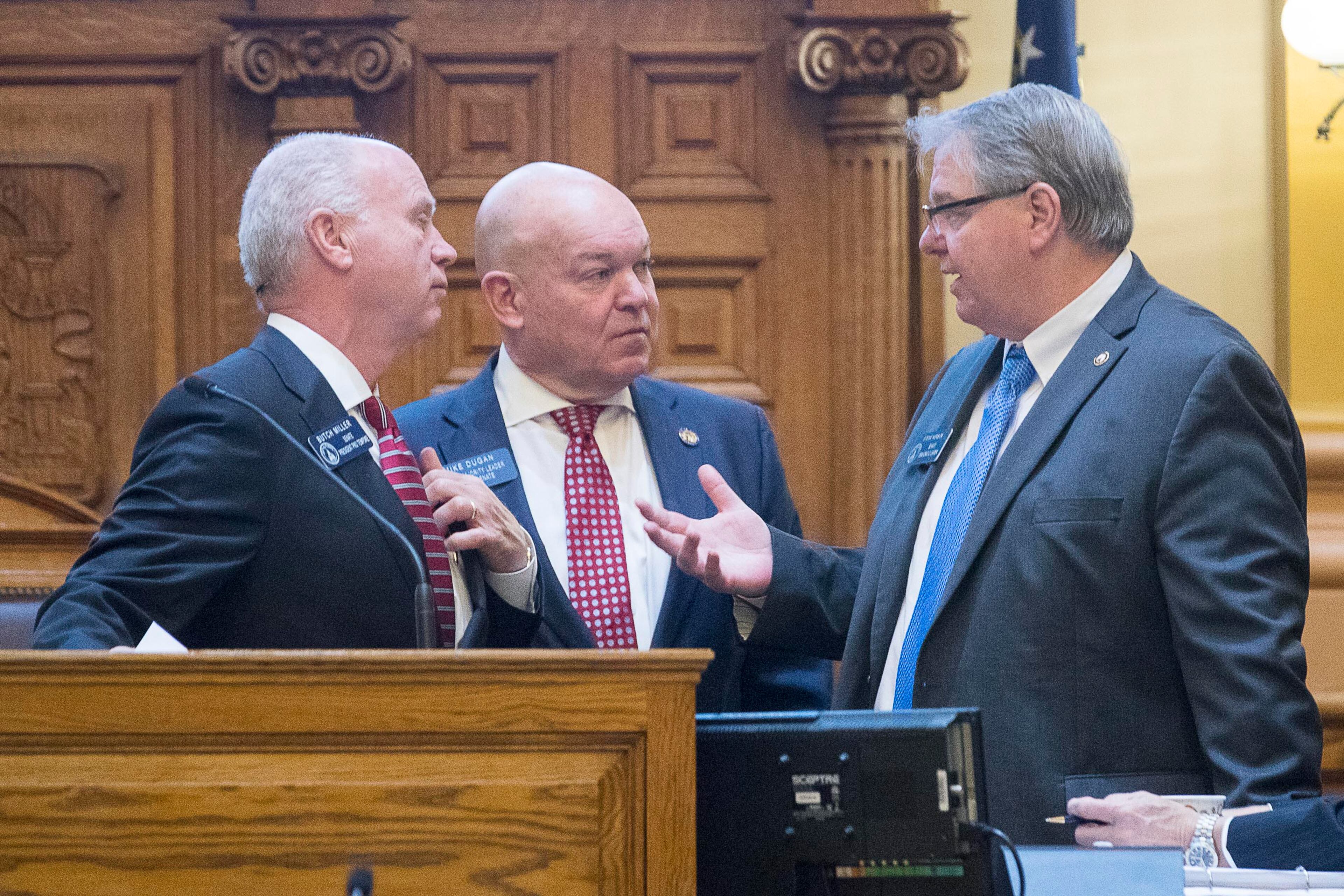

Senate President Pro Tem Butch Miller, a Gainesville Republican, said he believes there is room for the chamber to create an environment that’s more welcoming to women.

“We’ll never do enough for a cause that is just and right,” Miller said. “We’ll continue to work on it as a body.”

Currently, the highest-ranking woman in the Georgia Legislature is state Rep. Jan Jones, R-Milton, who in 2010 made history when she was tapped as House speaker pro tem, the chamber’s No. 2 position.

“I’m not about identity politics, but I will say the public does want to see folks who they identify with on many different levels, whether it’s geographic, age, background,” said Jones. “Gender certainly is one of them — you don’t want to deny that.”

“I encourage Republicans to own what they are on every level,” she added.

Among the House’s 41 committees, women chair only six. In the Senate, they lead four of 29. No woman, Democrat or Republican, has ever led the Legislature’s most influential panels: Appropriations, Rules and Ways and Means.

‘Not even in the ballpark’

Some of the lack of women in leadership roles comes down to longevity, said former state Rep. Jane Kidd. Many women don’t serve as long as their male counterparts, she said.

“If women do a couple of terms and choose to do something else, it’s probably because they didn’t feel like they were getting a lot done and making a lot of progress,” said Kidd, who lost a run for the state Senate after serving one term in the House in the mid-2000s.

Others have offered more pointed criticism.

Unterman last year excoriated leaders of her own party for sexism after she was ousted as head of the chamber’s health panel.

“Ladies of the Senate,” she said, “we’re not even in the ballpark. We’re outside looking over a fence, and we’re trying to look into the ballfield to see who is playing.”

Unterman eventually mended fences and was given a lesser committee. In an interview this spring, she insisted she felt valued by her colleagues and that she has been given opportunities to advance over the years.

“People eventually recognize your leadership skills, no matter if you’re a man or woman,” she said.

Still, the General Assembly has been criticized for its slow responses to problems that primarily affect women. It took years, for example, to address the state’s stubbornly high maternal mortality rate.

And, at times, lawmakers have seemed out of sync with women in the general public. In the wake of the #MeToo movement, state senators moved to limit the window for filing sexual harassment complaints against legislators when there had previously been no time limit.

And then, there are optics. Female lawmakers largely voted along party lines on last year’s “heartbeat” legislation, which outlaws most abortions once a doctor can detect a fetus’ “heartbeat.” But a much-circulated photograph depicted nearly three dozen smiling male lawmakers surrounding Unterman, the only Senate woman to support the measure.

For their part, Republican leaders in the Legislature say they will continue work to increase the ranks of women through active candidate recruitment and instituting family friendly policies.

Some noted the actions House leaders took last session to expand paid parental leave and extend Medicaid funding for low-income mothers as evidence of leaders taking women and their votes seriously. The paid leave proposal died on the last day of the legislative session, while Gov. Brian Kemp signed the maternal mortality legislation last month.

Several female legislators interviewed said they think it’s only a matter of time before women catch up — they point to record levels of female candidates. And there’s the rise of Jones and U.S. Sen. Kelly Loeffler for the GOP, as well as former House Minority Leader Stacey Abrams, who ran for governor and was a serious contender to become the running mate of Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden, and state Sen. Nikema Williams, the head of the Democratic Party of Georgia who was recently picked to succeed the late Congressman John Lewis on the November ballot.

There’s even been action on breastfeeding in the Georgia Capitol, although it was slow in coming. Last summer, Kemp opened a new lactation room for mothers in the Capitol complex, and Senate leadership installed a lactation pod in January.

The actions came too late for Harrell, who now leads the Women’s Caucus and whose children are young adults.

After Harrell’s phone call with Murphy 20 years ago, a sympathetic male chairman offered up his office in the Capitol when Harrell needed to feed her son.

Eventually, Harrell grew tired of missing votes to nurse in the chairman’s office. So, one day, she quietly slipped the baby into a sling and nursed him from her desk on the House floor.

“You should have seen how grown men were squirming,” said her colleague, state Rep. Carolyn Hugley, D-Columbus. “Things were changing in real time, and some were not prepared for that.”

ABOUT THE STORY

The ratification of the 19th Amendment, on Aug. 18, 1920, was a landmark moment for the nation and, specifically, women seeking the right to vote and hold office. In their fight to be counted, Georgia has been both friend and foe to women. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution examines those roles.

FEMALE REPRESENTATION IN GEORGIA

Female legislators as a percentage of the General Assembly:

2020 – 30.5%

Democrats: 13 in Senate, 42 in House

Republicans: 2 in Senate, 15 in House

2010 – 19.5%

Democrats: 7 in Senate, 27 in House

Republicans: 1 in Senate, 11 in House

2000 – 19.5%

Democrats: 9 in Senate, 26 in House

Republicans: 1 in Senate, 10 in House

1990 – 10.2%

Democrats: 1 in Senate, 18 in House

Republicans: 1 in Senate, 4 in House

Source: Rutgers University’s Center for American Women and Politics

WOMEN LEGISLATORS IN THE SOUTH

Female lawmakers as a percentage of state legislators in 2020:

Georgia: 30.5%

Florida: 29.4%

North Carolina: 25.3%

South Carolina: 16.5%

Mississippi: 16.1%

Alabama: 15.7%

Tennessee: 15.2%

Source: Rutgers University’s Center for American Women and Politics

FEMALE STATEWIDE OFFICIALS IN GEORGIA HISTORY

Governor: none

Lieutenant Governor: none

Attorney General: none

Secretary of State: Robyn Crittenden (appointed by Deal) 2008-2009, Karen Handel (R) 2007-2010, Cathy Cox (D) 1999-2006

State School Superintendent: Kathy Cox (R) 2003-2010, Linda Schrenko (R) 1995-2002

Commissioner of Agriculture: none

Commissioner of Labor: none

Public Service Commissioner: Tricia Pridemore (2018-present)

Source: Rutgers University’s Center for American Women and Politics