Companies have long been lured to Georgia by a business-friendly climate and generous tax incentives courtesy of the Republican-led state government.

But the willingness of conservative legislators in recent years to wade into divisive issues like abortion, religious liberty and most recently voting rights has squeezed many of those very businesses the state has spent millions to woo.

Most corporations are wary of taking stances that could alienate shareholders, customers or politicians. But they also have come under increased pressure to take stands on issues outside their economic wheelhouse.

That tension has boiled over in recent weeks after Delta Air Lines and Coca-Cola, two titans of Atlanta’s business community, condemned the GOP’s elections overhaul after initially appearing to support it.

The change of heart, after boycott threats and a public appeal from Black business leaders, prompted fury from Republican officials. House Speaker David Ralston cupped a Pepsi before his chamber stripped Delta of a tax break on jet fuel. (The effort later died in the Senate.)

“You don’t feed a dog that bites your hand,” said Ralston, R-Blue Ridge.

With the eyes of the nation focused squarely on Georgia as a political swing state, the quarrel may be a sign of what’s to come. Republicans are trying to energize their base after Georgia narrowly backed Democrats for president and the U.S. Senate. Meanwhile, many companies that have cultivated a more progressive image are being pushed to respond by employees, some investors and social media users.

“You can’t be a bystander in this day and age,” Sundar Bharadwaj, a professor at the University of Georgia’s Terry College of Business. “The decision making is about where, when and how to play, rather than whether to play.”

The political fireworks could complicate Georgia’s efforts to attract more corporations, such as the Georgia Chamber of Commerce’s “Red Carpet Tour” recruiting event at the Masters Tournament in Augusta this week.

“You can imagine people in a board room saying, ‘Really? Is Atlanta still on our top five list? This isn’t a good look for us,’” said Tom Smith, a finance professor at Emory University’s Goizueta Business School.

While the Masters golf tournament went forward, Major League Baseball decided to relocate its All-Star Game to Colorado. Critics of both the new law and corporations’ opposition to it say they’re still mulling boycotts against Georgia companies.

For decades, many companies focused their lobbying on financial issues such as tax rates to more parochial ones like sugar subsidies in the case of Coca-Cola.

Things began changing in 2015 and 2016 as state legislatures passed “religious liberty” proposals after the Supreme Court legalized gay marriage. Corporations and business groups argued such state measures were discriminatory toward LGBTQ people and threatened to pull investments.

The push worked. Shortly thereafter, Gov. Nathan Deal vetoed Georgia’s bill, saying it would threaten the state’s welcoming image. And North Carolina reversed course on its “bathroom bill,” which required transgender people to use the restroom that corresponded with the gender on their birth certificates, after the state was projected to lose more than $3.7 billion in business investment.

Critics of those companies’ political positions had a hard time countering them when they acted as a group, but it was much easier when a corporation acted alone. That’s what happened in 2018, when Delta ended a discount it offered for National Rifle Association members in the wake of the Parkland, Fla. school shooting.

Republicans seethed at what they saw as a Delta attack on gun rights and used the issue to rally their base ahead of that year’s gubernatorial primary. The legislature voted to halt the jet fuel tax break worth millions of dollars to Delta — though then-Gov. Deal later signed an executive order reversing it.

Choosing which issues to respond to and how has proven to be a challenge. Some progressives pounded Georgia companies for sitting on the sidelines as the state legislature debated a restrictive abortion measure in 2019.

After local businesses vowed to promote racial equity after last summer’s Black Lives Matter protests, several of Georgia’s Fortune 500s were called out last month by Democrats, voting rights advocates and Black church groups for not initially voicing greater opposition to the elections bills, which critics said would make it harder for people of color to vote.

“These companies seem to have missed the mark in terms of connecting the dots between what happened last summer and what was happening in the Georgia legislature just recently,” said Marvin Owens, a former NAACP senior director who now works for Impact Shares, a nonprofit fund manager that focuses on socially conscious investing.

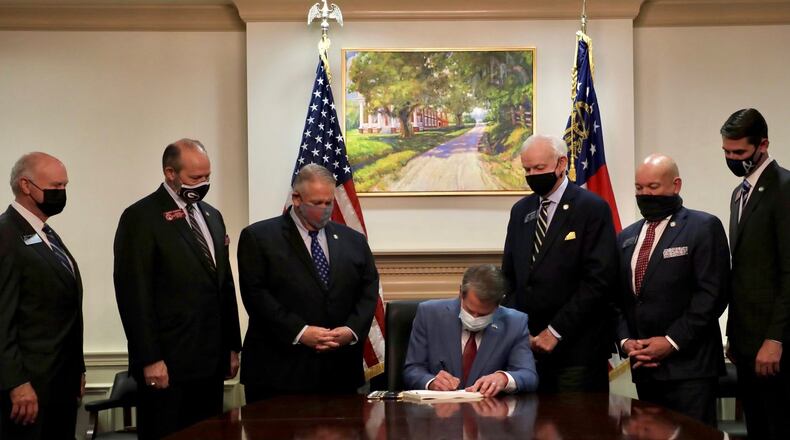

Delta and Coca-Cola changed their tune nearly a week after the bill was signed, and after more than 70 top Black executives placed a full-page ad in The New York Times warning the new law was “undemocratic and un-American.”

The move infuriated Republican lawmakers who said they worked hand-in-hand with those companies as the elections law was being drafted.

“I don’t think you’ll hear anybody on our side say that we don’t greatly respect them and the role they play,” said Bert Brantley, Kemp’s deputy chief of staff for external affairs. “I do think there’s some frustration out there because the process worked as it has so many times before and then we were blindsided. You had CEOs or whoever just completely turn their backs on all that work that was done at the capitol after months of discussions.”

Business experts are not expecting any of Georgia’s corporate behemoths to leave the state anytime soon — the companies have so much infrastructure and investment here that it would be hard to cut ties rapidly.

King R. White, CEO of Site Selection Group, which advises companies looking to relocate their headquarters, said political fights have paused the searches of some of his clients in the past. But, “I do believe that it really does start to fade away as soon as it leaves the media and things kind of get back to normal” after a few months.

White said leaders tend to make decisions on where to locate based on factors critical to their bottom line, like logistics, labor availability, economic incentives, tax conditions and a region’s infrastructure and quality of life.

“We consistently tell companies why this is a great place to live, work and play,” said Katie Kirkpatrick, CEO of the Metro Atlanta Chamber. “None of that changes through challenging times.”

But J.P. James, president of the entrepreneurship group TiE Atlanta, which has a funding and mentorship program for minority- and women-owned businesses in the Southeast, said he’s heard some companies “voice negative sentiment on the laws being passed,” and business-to-consumer companies in particular “are a little more hesitant in terms of the publicity.”

“It’s the image,” James said.

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured