The Southside Atlanta district of state Rep. David Dreyer splays out like a wobbly chair as it straddles both sides of the Downtown Connector. And somewhere among the tens of thousands of constituents the Democrat represents, two stand out: newly elected U.S. Sens. Jon Ossoff and Raphael Warnock.

The area has long been home to diverse working-class neighborhoods suffering from a lack of investment. Until a few years ago, some of them didn’t have easy access to a grocery store. And to Dreyer, the fact that Georgia’s two Jan. 5 runoff victors live in his district speaks loudly about the state of Georgia politics.

“Power no longer lies in homogeneous gated communities like Sea Island,” he said. “Power in Georgia now lies in diverse communities.”

As Georgia transforms from a Republican stronghold to the nation’s premier battleground state, a seismic geographic shift is underway.

No longer is the state’s political gravity squarely in sparsely populated South Georgia, as it was throughout decades of Democratic rule in the 20th century, or centered in the conservative bastions of North Georgia that dominated the state GOP through most of the 2010s.

Now, Atlanta and its suburbs have increasingly become the center of state politics, home to a burgeoning left-leaning electorate that fueled Democratic wins in November and January and the rise of homegrown politicians such as Stacey Abrams, Keisha Lance Bottoms and Jon Ossoff while also harboring a growing number of influential Republicans.

For only the second time since World War II, both of Georgia’s U.S. senators live in metro Atlanta — specifically, diverse neighborhoods inside the Perimeter and south of I-20. And for the first time in decades, Georgia Democrats are the key decision-makers in federal agricultural policy.

The gravitational pull has also drawn the GOP closer to Atlanta in recent years, with the rise of a new wave of Republican figures rooted in the bedroom communities surrounding Atlanta. The 2018 midterms ushered in new statewide leaders who hail from Atlanta or call the region home.

The shift toward Atlanta has had a profound impact on policy over the past decade, clearing the way for new immigration crackdowns, seat belt restrictions and Sunday alcohol sales that many in rural Georgia had opposed.

“We have been invaded by people that aren’t Southerners. And their thought process is just different,” said Kay Godwin, a longtime conservative activist from Pierce County. “They’re bringing a different mindset to Georgia in massive numbers.”

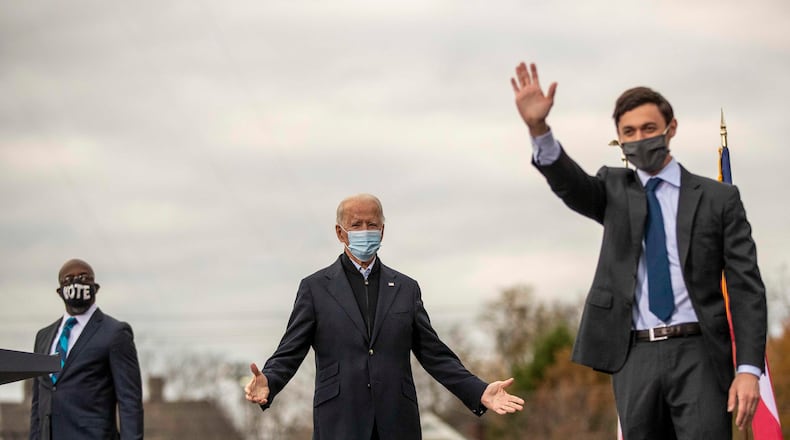

Credit: Stephen B. Morton for The Atlanta Journal Constitution

Credit: Stephen B. Morton for The Atlanta Journal Constitution

And it’s left fewer politicians with a deep background in the agrarian issues that have long powered the state’s economy, even as it paves the way for new voices that shape Georgia’s biggest industry.

“The real difference is Atlanta is becoming a place where you can win a statewide election, instead of a place you couldn’t,” said Jason Carter, the Democratic candidate for governor in 2014. “The metro area has always been a powerhouse, but now it has enough power to carry the state in an election.”

An Atlanta tilt

The inexorable pivot toward metro Atlanta isn’t altogether surprising. U.S. census figures show 60% of Georgia’s population now lives in metro Atlanta or the Athens area, accounting for roughly 6.2 million people. Georgia’s remaining 4 million-plus residents are scattered across the rest of the state.

And it mirrors the arc of Democratic politics in Georgia, as an influx of newcomers, an embrace of progressive policies and antipathy toward then-President Donald Trump turned the once solidly Republican suburbs circling Atlanta into the very bastions that cemented Joe Biden’s victory in November and GOP Senate defeats in January.

But it’s also affected Republicans, who control every statewide constitutional office and majorities in the state Legislature. All of Georgia’s constitutional officers are Republican, and all but one — Schools Superintendent Richard Woods — live in the northern third of the state.

Gov. Brian Kemp hails from Athens but lived part time in Atlanta long before he took up residence in the Governor’s Mansion. Lt. Gov. Geoff Duncan, Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger and Attorney General Chris Carr all live in metro Atlanta’s northern stretches.

Some of Georgia’s rural Republicans, meanwhile, are losing clout. Tom Graves, of the mountain hamlet of Ranger, was the state’s senior-most GOP member of the U.S. House delegation before he retired last year. He’s been replaced by Marjorie Taylor Greene, who ran for the seat from north Fulton County and has since been stripped of committee assignments for her hateful comments.

While metro Atlanta has long developed prominent political leaders, many of the state’s most powerful politicians have hailed from far outside the region, in part thanks to a voting system that for decades relied on “county units” and not individual votes to decide elections.

That unbalanced system gave rural areas five times as many assigned units as urban ones and shifted political power firmly away from Atlanta, even long after it was struck down by the courts in 1962.

Jimmy Carter, the governor-turned-president, came from the tiny town of Plains in southwest Georgia, while the Talmadge clan’s base of support was rural southeast Georgia. Former U.S. Sen. Sam Nunn and David and Sonny Perdue lived a few miles from each other in Middle Georgia. Dozens of other legislative and political leaders relied on their rural appeal to rise to power.

As Republicans swept into power in the early 2000s, Georgia’s political gravity lurched undeniably to the upper third of the state, led by then-Gov. Nathan Deal and then-Lt. Gov. Casey Cagle, both of Gainesville’s Hall County. House Speaker David Ralston, from mountainous Blue Ridge, formed a dominant triumvirate.

“It mirrors national politics,” said veteran GOP strategist Eric Tanenblatt. “Until this election, the federal power in Georgia was rooted in rural Georgia with Sonny Perdue and Tom Graves. Now it’s not.”

‘They can’t forget’

It’s not to say rural Georgia has lost its voice. Kemp’s background is farming and construction. Agriculture Commissioner Gary Black commutes from a farm in Commerce, in northeast Georgia. You’d be hard-pressed to call House Majority Leader Jon Burns a city boy from tiny Newington. And rural legislators hold key posts on legislative committees.

But now agricultural policies are being driven in a large part from Atlanta.

For the past four years, Sonny Perdue of the agrarian hub of Bonaire was the nation’s most powerful farm figure while serving as Trump’s agricultural secretary. Now, two of the state’s most important voices in the farm industry are Democrats in Atlanta.

U.S. Rep. David Scott, the first Black chairman of the House Agriculture Committee, represents an Atlanta district. Not long after Warnock was elected Georgia’s first Black senator, he was appointed to the Senate Agriculture Committee.

Credit: Louie Favorite

Credit: Louie Favorite

That newfound influence also comes with peril. When Mack Mattingly became Georgia’s first GOP senator since Reconstruction in a 1980 upset victory over Herman Talmadge, it was taken as a sign that the suburbs finally outweighed the rural precincts that had dominated state politics for so long.

Mattingly warned the same thing can happen to Democrats again if they get too heady.

“In 1980, when I ran, Democrats didn’t understand how much demographics changed in the state of Georgia,” said Mattingly, now retired to Georgia’s coast. “The demographics have changed again in the last few years. But they can’t forget the people in rural Georgia either.”

It’s one reason why Keith Mason, a veteran Democratic operative, helped orchestrate Biden’s trip in October to the rural town of Warm Springs for a closing campaign address.

“That type of campaigning is not just a marketing ploy. You’re never going to carry some of those counties,” he said. “But you can cut the margins. Atlanta will take care of itself politically for Democrats. But they’ve got to pay attention to the non-Atlanta areas.”

That’s not lost upon newly empowered Georgia Democrats. One of Warnock’s first proposals would include $5 billion in emergency relief for farmers of color struggling during the pandemic.

“Historically, (the U.S. Department of Agriculture) hasn’t been as responsive as it should to Black farmers,” Warnock said. “We will be vigilant and focused on making sure farmers of color get their fair share of support that comes from the USDA. So often, that doesn’t happen.”

The view from South Georgia remains guarded. Chase Daughtrey, a probate judge in Cook County, near the state line with Florida, said rural parts of the state are “terrified” about redistricting later this year that could further sap their influence by reducing the number of legislative seats representing the agricultural heartland.

“For rural Georgia to have political staying power,” he said, “we’re going to have to turn out in big numbers moving forward.”

Staff Writer Jennifer Peebles contributed to this article.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured