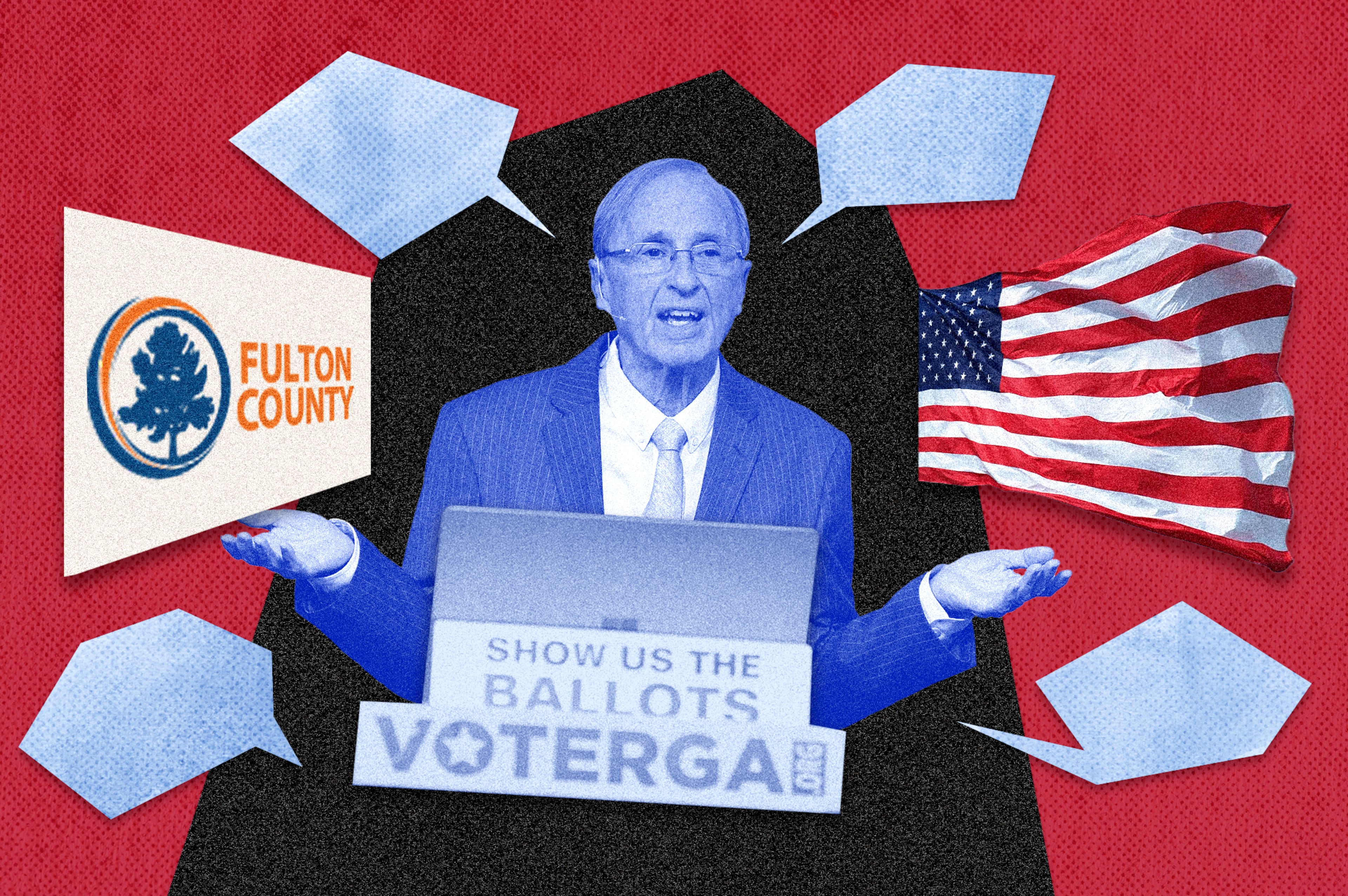

Georgia Trump electors at the heart of alleged ‘conspiracy’

On a cloudy Monday in December 2020, a small group of Republicans gathered in the Georgia Capitol. State GOP chairman David Shafer called the meeting to order at noon and and made sure there were 16 presidential electors. Then they rose one by one and signed paperwork certifying Donald Trump as the winner of the presidential election.

That meeting — which lasted just 31 minutes — is a centerpiece of Fulton County’s wide-ranging racketeering case.

Fulton prosecutors say the electors were part of a Trump conspiracy to overturn Democrat Joe Biden’s victory in the state.

The electors say they acted only to preserve Trump’s legal rights and had no idea their votes would be used to try to overturn the election in Congress on Jan. 6, 2021.

The courts will determine whether prosecutors or the defendants have the better argument. The first glimpse of an answer could come this week.

Three of the electors ― Shafer, state Sen. Shawn Still and former Coffee County GOP Chairwoman Cathy Latham ― were charged in an indictment handed up last month. They have asked a judge to transfer their cases to federal court. Legal observers say that’s not likely.

But today’s hearing gives prosecutors and the electors a chance to test their arguments in a courtroom. The electors played a crucial role in what prosecutors say was an illegal scheme to pressure state officials and Vice President Mike Pence to overturn the election.

Investigators have evidence that plan was under way before the Trump electors met to cast their ballots. But the electors have said they knew of no such plan.

John Malcolm, a former federal prosecutor now at the conservative Heritage Foundation, believes the charges against the electors are misguided. He said their actions were consistent with federal law and the U.S. Constitution.

“I think that they behaved perfectly reasonably,” Malcolm said. “They were trying to preserve a remedy for President Trump if he prevailed (in court).”

Georgia State University law professor Anthony Michael Kreis said Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis must prove the electors acted with criminal intent, and she may have more evidence than she’s made public to date. But he said it was clear by the time the electors voted for Trump that there was no widespread fraud to justify overturning the election.

“At that point, you have to ask yourself, what was their purpose?” Kreis said. “What were they being told?”

Origin of Trump’s plan

On the same day the GOP electors assembled at the state capitol, Democrats were also there.

The Democrats’ meeting was expected. They had gathered to cast their ballots for Biden. His slim victory had been confirmed by two recounts.

But the Republican one came as a surprise. When reporters spotted them, the Georgia Republicans electors initially turned them away. They later allowed the press to watch the vote when the meeting began in earnest. Shafer explained it was needed to preserve the viability of a pending Trump lawsuit challenging Biden’s Georgia victory.

That lawsuit claimed rampant fraud had cost Trump the election. Investigators found no evidence to support the allegations, and some Trump attorneys have admitted they were false. Trump filed similar lawsuits in other states Biden won. None succeeded in changing the outcome.

But by the time the Georgia electors met the Trump campaign was already planning to try to overturn the election in state legislatures or Congress, documents obtained by congressional investigators show. The Trump campaign was also convening electors in six other states Biden won.

Attorney Kenneth Chesebro, who was one of the 19 people charged in the Fulton County case, had laid out the idea in a series of memos beginning Nov. 18. He said the deadline for resolving election disputes in court was not the Dec. 14 meeting of presidential electors in the states, but Jan. 6, when Congress would count the electoral votes.

Chesebro said the extended deadline would allow Trump’s lawsuits to continue. But he argued state legislators or Pence (presiding in the Senate) could reject the Biden electors in favor of Trump electors – even if Trump had not yet prevailed in court.

Chesebro said having electors vote for Trump would be a crucial step.

Attorneys John Eastman and Jenna Ellis also helped craft Trump’s Jan. 6 strategy. Willis charged them and other attorneys for their roles in that plan. The attorneys say they offered good-faith legal analysis, and Willis is trying to criminalize aggressive lawyering.

Last year a federal judge called Eastman’s actions “a coup in search of a legal theory.”

The judge later found evidence that the primary goal of some lawsuits “was to delay or otherwise disrupt the Jan. 6 vote.” He cited an email in which Trump attorneys discussed a Georgia lawsuit, though it’s not clear which of the multiple lawsuits they were discussing.

“This email, read in context with other documents in this review, makes clear that President Trump filed certain lawsuits not to obtain legal relief, but to disrupt or delay the Jan. 6 congressional proceedings through the courts,” the judge wrote.

What did the electors know?

When the Republican electors met, Shafer told them their votes were needed to protect Trump’s legal rights if he succeeded in court.

“And if we did not hold this meeting, then our election contest would effectively be abandoned,” Shafer said, according to a transcript of the Dec. 14 meeting.

Trump attorney Ray Smith, who filed one of the lawsuits, was in the meeting and told the electors the vote was needed “because the contest of the election in Georgia is ongoing.”

Shafer and Still told congressional investigators the same thing. They also said they had no idea when they cast their ballots that they would play a role in the Jan. 6 congressional debate over whether to affirm Biden’s victory.

“It would not have occurred to me that the vice president could make that decision on his own,” Shafer told investigators.

In the federal indictment against Trump obtained in Washington, special counsel Jack Smith appeared to back up such testimony when detailing how Trump and his co-conspirators allegedly organized slates of electors.

“Some fraudulent electors were tricked into participating based on the understanding that their votes would be used only if (Trump) succeeded in outcome-determinative lawsuits within their state, which the defendant never did,” the indictment said.

In court filings, the three electors charged in Fulton County say they were “contingent” electors under federal law and acted under Trump’s authority as president. They say they’re entitled to have their cases tried in federal court – where they could be judged by jurors from across the greater metro area, which is more politically conservative than solidly Democratic Fulton County.

Fulton prosecutors say the Republicans were not electors at all but were impersonating electors in a fraudulent scheme. They say Trump acted as a candidate for office, not as president. And they say even the official Biden electors are state officers, not federal officials.

There is evidence the electors could have known their votes were about more than winning in court.

Chesebro emailed Shafer two memos laying out his legal theories. The first suggested state legislatures could overturn the election, and the second said the electors could be recognized “by a court, the state legislature or Congress.” Shafer told congressional investigators he didn’t read the memos.

Before the electors met Rudy Giuliani and other Trump attorneys were already pressing Georgia lawmakers to pick the Republican electors in well-publicized hearings. Shafer told investigators he didn’t watch, though he was aware there was a debate over whether lawmakers should convene a special session to consider appointing Trump electors.

Shafer told investigators he believed “there should not be a special session of the General Assembly until there had been a determination through the judicial process that the original (election) certification was invalid.”

Willis charged only three of the 16 Republican electors, though the indictment calls the others “co-conspirators.” A prosecutor in Michigan has charged all of that state’s Trump electors for their roles in Trump’s plan.

The three Georgia electors are charged with racketeering, impersonating a public officer, forgery and other crimes. Their attorneys did not immediately return phone calls seeking comment.

Staff writer Bill Rankin contributed to this report