‘Tis the season to gut and replace at the Georgia Capitol

Georgia House Speaker Jon Burns’ proposal to double the state homestead exemption on property taxes would do nothing for most of the state and save little for those who could use it, Senate leaders said Monday.

So Tuesday, the Senate Finance Committee took another bill that had already passed the House and turned it into Senate Bill 349, a measure to cap how much home assessments can go up each year at 3%.

Welcome to the General Assembly’s annual season of gut and replace.

“We have seen double-digit property tax increases in almost every county in the state,” said Sen. Greg Dolezal, R-Cumming, a member of the Senate committee. “I think this is the best news we could take back to our constitutents, that the days of double-digit tax increases are over under this plan and that we stop, particularly school systems, taxing people out of their homes.”

The Senate bill had already passed the chamber in February, but with seven working days left in the 2024 General Assembly session, senators said it hasn’t gotten a hearing in the House Ways and Means Committee.

Meanwhile, Burns’ proposal to double the standard state homestead exemption on property from $2,000 to $4,000 a year got a Senate committee hearing Monday. But it didn’t go so well.

By lowering the taxable value of a homeowner’s property, such exemptions cut his or her tax bill.

“Increasing the state minimum is good for homeowners statewide,” said Rep. Matt Reeves, R-Duluth, the sponsor of House Bill 1019.

But Reeves said the change would only affect taxpayers in a third of Georgia counties because most already have homestead exemptions that are higher than the standard state exemption.

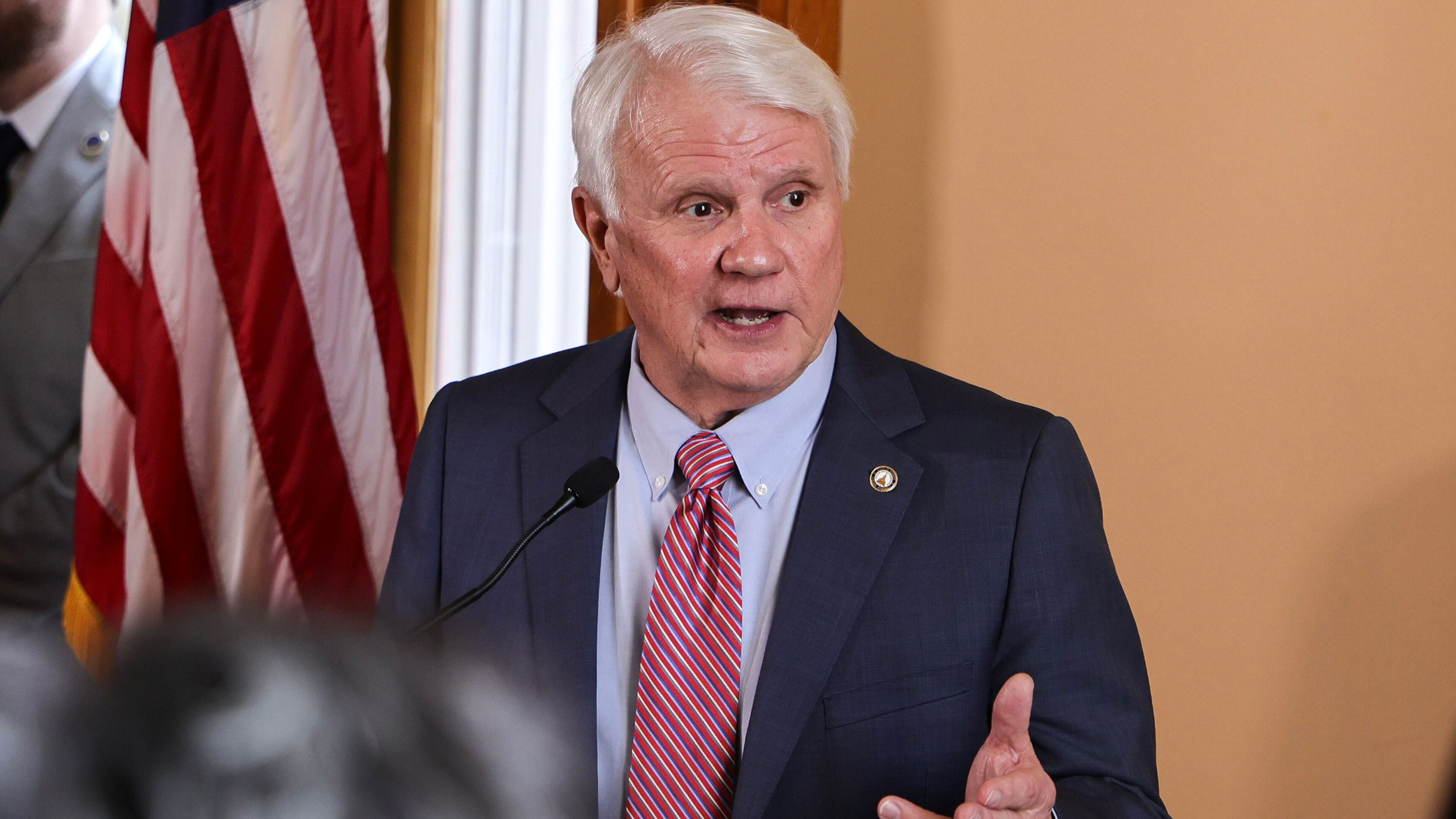

Senate Finance Chairman Chuck Hufstetler, R-Rome, said in his county homeowners would save $24 a year on property taxes.

“I think we need to do more than this,” he said. “Basically, (people in) two-thirds of counties don’t get a dollar of tax relief.”

Senate Appropriations Chairman Blake Tillery, R-Vidalia, said of House Bill 1019, “I am concerned if we pass this, that this becomes the bill that everybody says, ‘Hey, we did something.’ ”

Both the House and Senate bills aim to respond to complaints from homeowners who, in some areas, have said they are being taxed off their property as assessments have skyrocketed with the booming housing market.

A homeowner’s property tax bill is mostly made up of two elements: the tax rate and the assessed value of the property. School districts, cities and counties have been able to count on a boost in revenue without raising tax rates because the assessed values of homes and businesses in some areas have risen sharply.

Senators say about 75% of what homeowners pay goes to schools, and local governments have been taking in double-digit increases in revenue without raising the tax rate.

The Senate’s 3% cap on unimproved property assessment increases could mean local governments and schools would have to raise tax rates, but some lawmakers say at least that would make the process more transparent to homeowners, many of whom don’t understand why their home is valued at what it is.

Gutting and replacing bills has long been common during the final few weeks of every legislative session, particularly when a bill is being pushed by a House or Senate leader.

While Burns is backing the homestead exemption bill, the Senate measure is sponsored by Hufstetler and has the support of Lt. Gov. Burt Jones, the Senate’s president, and Tillery, the chamber’s budget chairman.

For now, Burns’ proposal remains alive but on hold in the Senate committee. The senators chose to gut a separate House tax measure.

Gut and replace also isn’t necessarily a one-for-one swap. A gut and replace bill can become a vehicle for five or six measures that stalled in one of the chambers. The final product is referred to as a “Christmas Tree” or “Frankenbill” by the time it gets a vote, typically on the 40th and final day of the session.

Lawmakers sometimes receive advanced notice that their bills will be gutted. Other times they find out when they show up at the committee meeting where the gutting occurs.

Rep. Beth Camp, R-Concord, whose House bill was gutted Tuesday, did not attend the Senate Finance Committee meeting where the replacement legislation was approved.

“I told her she didn’t need to be here,” Hufstetler said.