Preparing for the worst, Georgia election officials and police plan ahead

DALLAS — It isn’t hard to imagine elections disrupted by rowdy groups claiming fraud at polling places, social media posts that spread disinformation or a credible domestic terrorist threat.

Georgia election officials and police are preparing for these kinds of hazards ahead of this year’s contentious presidential contest.

During a training exercise last week at Paulding County’s election office, sheriffs and election officials talked through how they would both ensure public safety and protect voting from interference.

“Hopefully it will not grow and get worse than it did in 2020, but I think there’s a chance it will,” said Chris Harvey, a former Georgia elections director who now oversees law enforcement training. “We’re not trying to make you really paranoid; we’re trying to make you a little paranoid and to plan for worst-case scenarios.”

The threat to elections and election workers isn’t theoretical. In an article published last fall in the publication Lawfare, counterterrorism researchers Pete Simi and Seamus Hughes wrote that more than 500 people across the country over the past decade have been charged in federal court with threatening public officials.

“And the trendline is shooting up,” they wrote.

In the Paulding County training, officials broke into groups and walked through the scenarios, thinking about how they would handle problems big and small.

How would they talk to a disgruntled voter raising a fuss in a polling place? What would they do about aggressive people who claimed to be poll watchers and demanded access? What would happen if they needed to evacuate?

Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger said Georgians need to know their votes will be accurately recorded, kept safe by election officials and law enforcement.

“I know how contentious and how polarized this is. Elections should be safe and secure when you’re exercising your precious franchise,” Raffensperger said after the training session, the fifth so far across the state.

Serious problems at polling places would require a police response. Election officials would need law enforcement if there were a bomb threat, voter intimidation or interference while election workers tried to count votes.

Minor situations could be managed by election officials, such as talking through a voter’s concerns in a quiet corner or by countering disinformation on social media platforms.

“Election threats are real, and we need to take them seriously,” Paulding County Elections Director Deidre Holden said. “November is going to be crazy. That’s usually when the most people come out, and you don’t want people to be agitated.”

But there aren’t always easy answers to potentially dangerous situations.

If there were a threat to voters’ safety, protecting them would take priority over keeping a polling place open, creating a risk that voters would face waits or decide to go home instead of casting their ballots.

In 2020, the most heated controversies affected election officials outside of polling places.

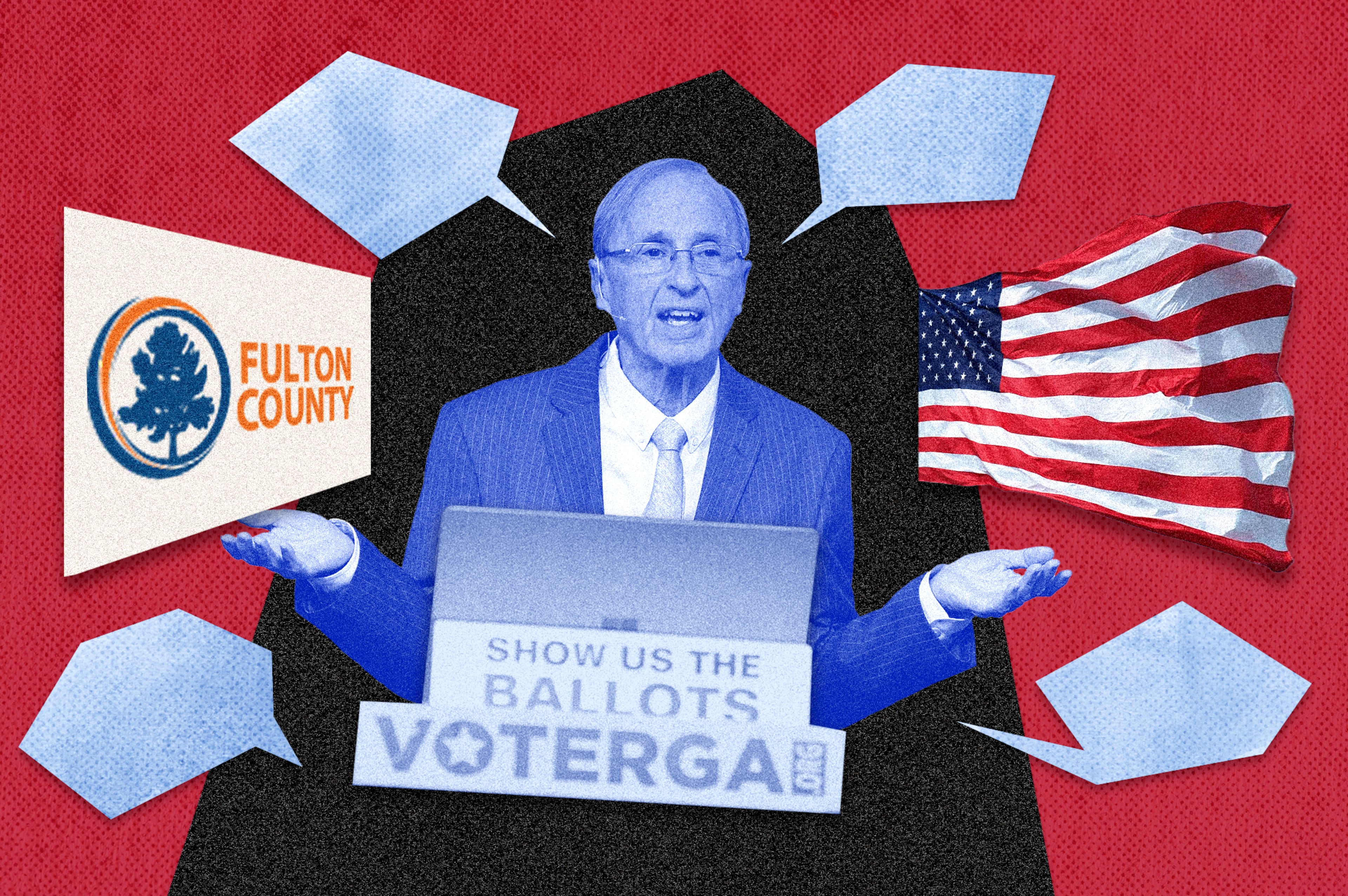

Election workers such as Ruby Freeman faced threats after they were falsely accused of fraud in Fulton County. Raffensperger and election directors were pressured by Donald Trump and his allies. And Republican election skeptics launched a barrage of conspiracy theories that in some cases took weeks or months to disprove.

This year, police and election officials say they’ll be prepared.

Law enforcement agencies should approach elections with the same kind of planning as a major event like the Super Bowl or a large convention, Harvey said.

Police received a seven-page quick-reference guide, outlining Georgia laws against election interference, violent threats or carrying firearms within 150 feet of a voting location.

The training session focused on physical threats at election locations. Future sessions will likely include responses to other types of risks, such as cybersecurity.

“Tensions are high, and you never know what’s going to be around the next corner,” Georgia Elections Director Blake Evans said. “The way to prepare for that is to talk through scenarios before that. Everyone is taking it seriously.”