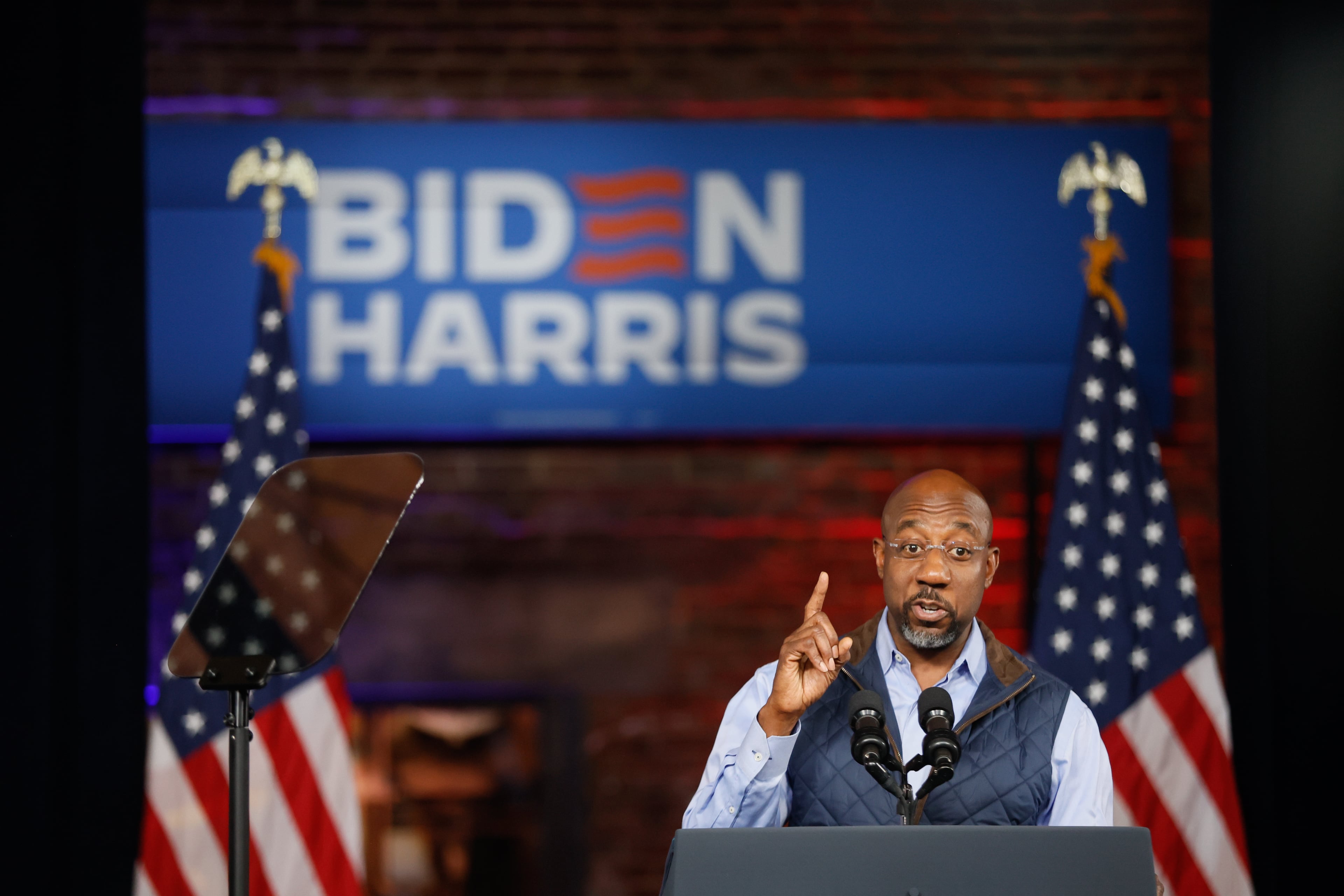

From arm’s length to indispensable: Warnock now a top Biden ally in Georgia

As threats of boycotts swirled, one of Morehouse College’s most prominent graduates tried to calm the political waters over President Joe Biden’s scheduled commencement address at his alma mater.

“I could not be more thrilled and honored,” U.S. Sen. Raphael Warnock said about Biden’s May 19 visit, adding that he was expecting a “timely, poignant, forward-looking message” for the Morehouse graduates.

For much of his first two years in office, Warnock took steps to steer clear of Biden as he fought a 2022 reelection campaign, scoring the only statewide Democratic win to offset what was otherwise a red wave in Georgia.

But with another term safely in hand, Warnock and Biden are now more closely linked than ever as the president fights to repeat his victory in Georgia.

“The work is sharing the good news, telling the story. I’m proud to join the president in doing that, not only in Georgia but across the length and breadth of the country,” Warnock said in an interview. “Because we are at a moral inflection point in our country.”

Their alliance will be a key factor in the party’s quest to rebuild the tenuous coalition that defeated then-President Donald Trump in 2020, even as party leaders fret about apathy and disenchantment with Biden’s agenda.

Democrats see Warnock as a rare politician who can help mobilize not only the Black voters who are the pillar of the party, but also white swing voters who were a key factor in Democratic wins the past two elections.

“He’s exactly the kind of person you want to be a surrogate,” said Jason Carter, a Warnock friend who was the party’s nominee for governor in 2014. “He’s able to reach beyond the Democratic base, connect with voters and speak to issues.”

As pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church, Warnock commands the pulpit of the nation’s most famous Black congregation, giving him a platform on moral and religious issues confronting the nation.

But he’s also a battle-tested candidate who drew solid support from more moderate voters who once reliably voted Republican but helped Warnock finish first on the ballot in five elections between 2020 and 2022.

A bloc of those voters split their ticket two years ago, backing Gov. Brian Kemp and other statewide Republicans while also siding with Warnock over Republican Herschel Walker, whose troubled campaign split Georgians.

One reason is savvy media messaging — sometimes cheeky, sometimes earnest — that helped the senator blunt efforts to brand him as a “radical liberal” and instead position him as an everyman.

“He’s a politician that people still don’t really see as a politician. They see him as a good person who happens to be in politics,” said Wendy Davis, a Georgia member of the Democratic National Committee.

To Republicans, Warnock’s reticence to embrace Biden two years ago shouldn’t be soon forgotten by voters torn over a rematch that many dread.

“I understand that Democrats are going to rally around the incumbent,” said Martha Zoller, a conservative commentator and former U.S. House candidate.

“But,” she said, “it seems to me the same questions that Republicans get asked about Donald Trump should be asked about why Democrats are supporting Biden.”

‘Dangerous proposition’

Biden and Warnock campaigned together, along with Democrat Jon Ossoff, in Georgia’s 2020 campaign.

After Ossoff and Warnock scored upset 2021 victories in U.S. Senate runoffs, their votes helped pass Biden’s most important legislative priorities, from a flood of COVID-19 relief to a health care and climate change spending and tax package.

But Warnock kept Biden at arm’s length during his reelection campaign a year later to muffle GOP attempts to link him to the president’s low approval ratings and the inflationary economy that drove so many campaign attacks.

When asked then why he distanced himself from Biden, Warnock regularly replied that everyday voters don’t care about “pundit” speculation but are focused on pocketbook issues that divided him and Walker.

The few times Warnock invoked Biden’s name on the campaign trail came in carefully calibrated comments about specific issues, such as his demands for more robust student debt relief.

A veteran of a half-century in politics, Biden had no hard feelings about Warnock’s strategy, his aides said, acknowledging that candidates in competitive states would have to demonstrate their independence.

Warnock, for his part, said he tried to focus on the policies that animated his campaign, including new federal voting protections and abortion rights.

“I’ve been working on these issues for years, long before I knew I would even enter into politics,” Warnock said. “So it was important for me in 2022 to stay focused on Georgia because that’s what it was about.”

It was a strategy honed in part by Quentin Fulks, who is also Biden’s deputy campaign manager and one of a small clutch of Georgians in the president’s inner circle. Fulks called Warnock an “invaluable partner” to Biden.

Shortly after Warnock’s 2022 victory, the senator invited Biden to address Ebenezer. The two embraced before a crowd of Sunday churchgoers, and Biden made clear there were no ruffled feathers.

Since then, Warnock has increasingly positioned himself as an outspoken defender of the president.

When Trump urged supporters to buy $59.99 branded Bibles, Warnock garnered national headlines when he flatly declared: “The Bible does not need Donald Trump’s endorsement.”

He has headlined about a dozen events for Biden and other Democrats across the nation, and he has appearances scheduled in the next weeks in South Carolina and Virginia. It’s travel that also could factor into Warnock‘s next political steps, when he could wage a White House bid in 2028 or beyond.

And as polls showed a tight rematch in Georgia — and signs of apathy among liberal voters of color who once flocked to Biden’s standard — Warnock has countered the sky-is-falling narrative.

“Georgia voters — Black voters included — are going to show up for Joe Biden the same way they showed up for me,” he said. “Not to vote is to vote. It is to push Donald Trump a little bit closer to the White House. And that’s a dangerous proposition.”

‘We know how to debate’

Biden’s speech next week at Morehouse will mark another political milestone in Georgia — though it may be a fraught one.

Some students and faculty upset with Biden’s approach to the Israel-Hamas war, or frustrated by his domestic agenda, have urged Morehouse to rescind the invitation to the president and threatened to boycott his speech.

Though the pushback hasn’t played out visibly in the form of on-campus demonstrations, Morehouse has a tradition of civil rights protests and is the alma mater of Martin Luther King Jr., where he joined the debate team and, as a freshman student, was introduced to the concept of nonviolent direct action.

Asked about the threat of Biden backlash, Morehouse Provost Kendrick Brown invoked both King and Warnock, a 1991 graduate, as examples of the school’s legacy of “public advocacy and activism.”

He added that “even when you have strong opinions that might be in conflict with others in that community, you still uphold safety and ensure that these voices can be heard.”

Warnock, too, is careful not to criticize students and others who might protest Biden’s appearance. It was Morehouse, after all, that helped nourish Warnock’s sense of activism — what he calls a demand to be a “candle in this present darkness.”

But he also said he views the talk of deep discontent of Biden on Morehouse’s campus as overblown, mentioning White House initiatives that pumped more than $7 billion in federal funding into historically Black colleges and efforts to forgive about $150 billion in student debt on Biden’s watch.

“It narrows the racial wealth gap, and I think Black students at Morehouse College and all across our state care a whole lot about that,” Warnock said.

Of the upcoming visit, the senator said there’s a “great deal of excitement” about Biden’s commencement speech.

“And there are those who have a difference of opinion,” Warnock said in the interview. “That’s the way it’s always been at Morehouse. We know how to disagree. We know how to debate. And at the end of the day, all of us are better because of it.”