First census numbers coming soon, kicking off Georgia’s redistricting process

There are no friends when it comes to redistricting.

That’s how University of Georgia political scientist Charles Bullock, who wrote a book on redistricting, puts it.

Redistricting is the majority party moving voters around, drawing political lines to help it maintain control, and the minority party trying to hold onto the seats it has, knowing that it doesn’t have the votes to do so. It’s individual legislators and congressmen lobbying to protect their own turf, knowing that in some cases, what they do may endanger the political careers of some of their colleagues who will get less favorable districts.

“There will be blood on the floor,” said Bullock, author of “Redistricting: The Most Political Activity in America.”

Every 10 years, Georgia lawmakers are tasked with redrawing legislative and congressional lines based on numbers from the U.S. census to ensure each district has an equal number of constituents.

Each state gets to decide how it draws the district lines, with Georgia assigning state lawmakers the task. The majority party in the General Assembly is in control.

Not all states do it that way. States such as California and Ohio use nonpartisan redistricting commissions to draw district boundaries, while states such as Missouri and Pennsylvania use bipartisan commissions.

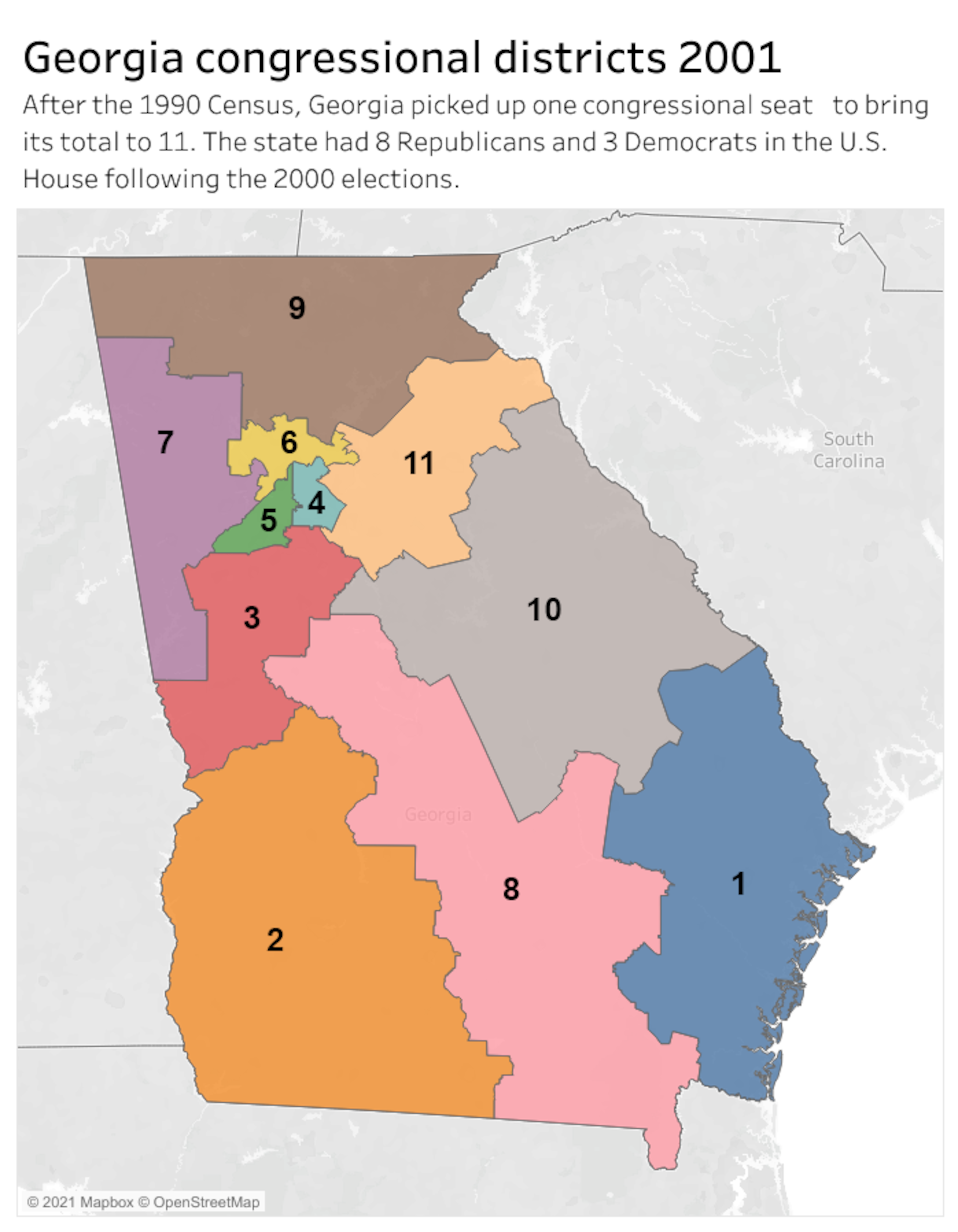

Lawmakers are expected this week to get their first glimpse of how much Georgia has grown in the past 10 years, when the U.S. Census Bureau is slated to release the official statewide population totals that are used to determine how many congressional seats each state will be allotted. It’s unclear whether Georgia — which has 14 members in the U.S. House — will gain another seat.

Details on where exactly those additional Georgians reside won’t come until later this year, which is when lawmakers will begin the task of drawing legislative and congressional district lines.

It is the first step in a yearlong, brutally partisan process to determine legislative and congressional districts, which will be mapped out during a special session this fall. The release of official numbers has been dramatically delayed due to the coronavirus pandemic and the amount of time census workers spent trying to account for the country’s residents.

And after Democratic wins in the presidential and U.S. Senate race, followed by the overhaul of the state’s elections laws, redistricting is expected to be the next huge political fight.

House Speaker David Ralston, a Blue Ridge Republican, said he expects the special legislative session dedicated to redistricting to be so late in the year that it potentially “bumps up” against the regular General Assembly session that begins in January.

‘They’ll look out for their own’

The new district lines for the General Assembly and U.S. House will be used in the 2022 elections.

Ralston has repeatedly bragged that the maps drawn in 2011 — over which he presided — were approved by the federal government, not necessarily a small thing. Georgia, at the time, was one of 16 states that needed approval from the U.S. Justice Department due to the Voting Rights Act.

The federal Voting Rights Act, at the time, required states such as Georgia with a history of discriminatory practices to obtain federal clearance — a process known as preclearance — before making changes to elections.

“One of the things I’m most proud of as speaker is that those maps were reviewed and approved under the Obama Justice Department by Attorney General Eric Holder and found to be satisfactory — no changes were made,” Ralston said.

Still, lawsuits were filed, and were ultimately unsuccessful, in challenging the maps — as they are after every redistricting, usually by the minority party.

Then, in 2013, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled the approval process established by the Voting Rights Act was no longer necessary.

That’s something Georgia Senate Democratic Leader Gloria Butler of Stone Mountain said she worries will give Republican lawmakers more leeway to draw oddly shaped districts and group voters who may support specific candidates based on their demographics, which is common in redistricting.

“We have to worry about that and making sure we get fair and just maps drawn,” she said. “I know that they’ll look out for their own. And that’s what I’ll be doing — trying to look out for our own.”

Republicans currently control both chambers of the General Assembly and will use voter shuffling to cement their majorities in the General Assembly and congressional delegation for the next decade.

Democrats are bracing for the new maps to be configured in a way that costs them all the ground they gained in recent years and could leave some of the party’s legislators in GOP-leaning districts.

And though Georgia supported the Democratic candidate for president in November and sent two Democrats to the U.S. Senate, things didn’t go as well in the state legislative elections.

Democrats fell well short of their goal of flipping 16 state House seats from Republicans in last year’s election, instead only taking three districts — and losing one. It was a far cry from their 2018 performance, when they picked up 11 seats in the chamber.

On the other hand, Democrats in Georgia picked up two suburban congressional seats in recent years. Republicans may look to either shove some of the Democrats into the same district or add rural, conservative voters to each of the current districts, making them more likely to flip back to the GOP.

With Congress so evenly divided, every district Democrats lose brings the U.S. House one step closer to going back to a Republican majority. Nationally, there are more Republican-dominated state legislatures than Democratic ones, making it likely that the new maps will give the GOP a strong chance of taking over the U.S. House in 2023.

There has also been some talk at the Statehouse that the GOP might tinker with the northwest Georgia district represented by first-term U.S. Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene, a Rome Republican, because of some of her controversial statements before and since her election and because some legislators consider her a loose cannon. However, members of the U.S. House aren’t required to live in their districts and Greene has been willing to move to run for office in the past, so there may be nothing her critics can do.

A new political landscape

Bullock, who has spent the past half-century teaching political science at UGA, said things will be vastly different than when lawmakers redistricted the state 10 years ago.

“Ten years ago (Republicans) were close to their peak in terms of support, so they didn’t have to go through and create extraordinarily shaped districts in order to come out with maps that gave them majorities,” Bullock said.

Now Georgia is closer to a 50-50 state, he said, so the GOP majority’s redistricting machinations to retain control could dramatically increase.

Bullock said the number of “marginal” legislative districts — mainly in the northern Atlanta suburbs, where Republicans narrowly held onto their seats — has increased since the last time districts were drawn and that may lead GOP leaders to choose to sacrifice some lawmakers.

“The real hard decisions that Republicans are going to have to make is how many of their current members are they going to be willing to try to protect?” Bullock said. “If they focus on drawing, say, 95 (House) districts to hold on through the decade, they may have a better chance of holding control of the chamber than if they try to protect everyone.”

After the 2020 elections, there are 34 Republican and 22 Democratic state senators. In the House, 103 representatives are Republicans and 77 are Democrats.

Republicans have held onto majorities in the state House and Senate throughout the 2010s in part because of the district maps they drew early in the decade. State legislative leaders essentially decide which Georgians will vote in which districts, and by divvying up the population in a partisan manner, they can draw district lines that make it highly likely they will win a certain number of seats.

This year much of the focus will be on metro Atlanta, especially in increasingly diverse Gwinnett County. According to the 2000 U.S. census, Gwinnett’s population was two-thirds white. As the number of Black, Asian American and Hispanic residents has grown, the white population dropped to nearly 54% in 2019 census estimates.

“There’s not much you can talk about until we get the data,” Butler said. “But there is a population shift that has taken place. The white population has decreased and Black population has increased. Hopefully that’s in our favor.”

Black Georgians, especially those in urban centers, have overwhelmingly supported Democratic candidates, while white voters in the exurban and rural areas overwhelmingly vote for Republicans.

Regardless of how the maps are drawn, legal challenges are expected. But without the preclearance provision of the Voting Rights Act as a guideline, it may be difficult to win in court.

“There are always lawsuits. If you lose in the Legislature, then you turn to the courts,” Bullock said. “But don’t waste your time saying you’re the victim of partisan gerrymandering. The courts have shown that’s not a winning argument. You’d have to contend there was a racial gerrymander.”

The U.S. Supreme Court in 2019 ruled that partisan redistricting is a political question and not one that can be reviewed by federal courts. That means those courts can’t judge whether extreme gerrymandering, where those drawing the maps manipulate district boundaries in their favor, violates the Constitution.

Ralston said the Republican majority — which will be able to pass anything it produces — will follow the law.

“We’re going to follow the legal principles and constitutional requirements as though (the maps) were going to be reviewed (by the Justice Department),” he said. “I’m optimistic and hopeful that we’ll have a smooth session.”

Bullock, however, was less optimistic. Redistricting sessions aren’t about bipartisan love. They are highly contentious, full of tears, backroom deals and the odd back-stabbing.

“I mean, the subtitle of my book is ‘The most political activity in America,’ ” he said. “And, yeah, it really is.”

Why it matters

Every 10 years, states draw new legislative and congressional district lines based on U.S. census numbers. In Georgia, the General Assembly performs that task. Lawmakers should get their first glimpse of those figures in the coming week, with more specific numbers coming before the Legislature meets in special session later this year to draw the final maps. The majority party traditionally uses this as an opportunity to draw political lines to maintain control, and the minority party often challenges the final maps in court.