DARIEN — The Sapelo Island ferry began its slow passage across the Doboy Sound more than two hours late Tuesday night, just before dusk. The mood of those onboard reflected the darkening skies: They’d just witnessed three elected officials bless a law change that they consider a threat to their way of life, leaving them feeling a mixture of outrage and hopelessness.

“This is going to continue; this is just the next step,” said Maurice Bailey, whose family has called the Hog Hammock community on Sapelo Island home for nine generations. “What’s next? I don’t know, but I do know it won’t be good for us.”

Bailey is Gullah Geechee, a descendant of enslaved West Africans who once worked Sapelo’s Spalding Plantation. Those slaves formed Hog Hammock in the 1850s and, once freed, began purchasing land, eventually accumulating 434 acres on the isolated barrier island. Today, the ferry is the only connection to the mainland.

Bailey and dozens of other full-time Sapelo residents, many of them also Gullah Geechee, joined about 125 others at Tuesday night’s McIntosh County Commission meeting to hear a decision on a zoning proposal for island dwellings.

The new law increases the allowed square footage from 1,400 square feet of heated-and-cooled space to 3,000 square feet under roof for houses in Hog Hammock. The rest of Sapelo’s 16,000 acres are protected land owned by the state.

Credit: AP

Credit: AP

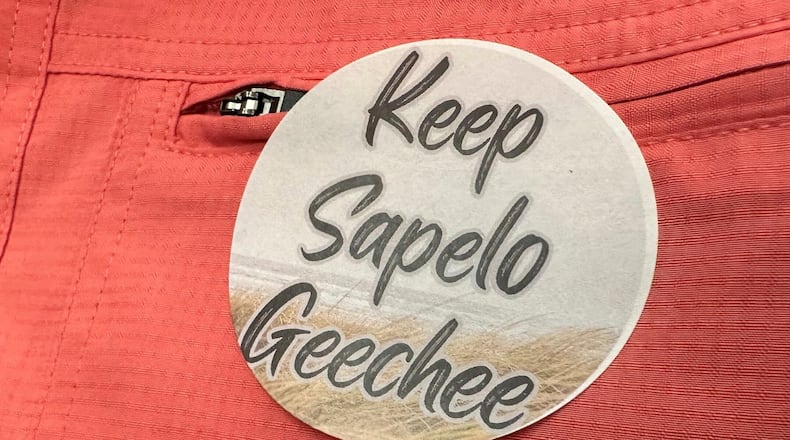

The change, more than two years in the making, passed by a 3-2 vote. The tally sparked protest from the crowd, almost all of them wearing shirt stickers calling to “Keep Sapelo Geechee,” as well as readings of prepared statements from commissioners on both sides of the debate.

“This is meant to allow modest homes where whole families can stay under one roof,” said Commissioner David Poole, who voted for the zoning amendment. Later in his statement, he added, “The change will not destroy the culture of the Gullah Geechee or the heritage of the Gullah Geechee.”

The commission’s chairman, David Stevens, offered a more pointed assessment: He blamed the Gullah Geechee for necessitating the zoning change, pointing to the sale of Hog Hammock properties to nondescendants and a current generation of Gullah Geechee who lack the cultural appreciation shown by their ancestors.

“This next new generation doesn’t have it, nor will they ever,” he said.

Changing demographics

The zoning change pitted Sapelo’s ancestral residents ostensibly against a group of the island’s nondescendant property owners. The identities of those who favor the zoning change are unknown to the Gullah Geechee as well as the general public — none of them spoke in favor of the zoning change at previous meetings.

But Stevens and Poole made mention of representing “all residents” in their remarks. Fellow Commissioners Roger Lotson and William Harrell, who opposed the zoning amendment, said they suspect a “relationship” between the three pro-change commissioners — Stevens, Poole and Katie Pontello Karwacki — and the residents pushing for the larger homes.

Credit: AP

Credit: AP

The number of nondescendant property owners is in dispute. Poole said “50%” of Hog Hammock’s approximately 100 properties have been sold to outsiders over the years.

Bailey challenges that count. He has acknowledged that of the original 44 Gullah Geechee families who formed Hog Hammock, fewer than 10 still own land on Sapelo. However, a 2022 survey conducted by his organization, Save Our Lands Ourselves, placed the non-Gullah Geechee owner percentage at closer to 30%, not including the 180 acres owned by the Sapelo Island Heritage Authority.

The authority is a state-established entity that by law has preference in purchasing properties listed for sale on the island. The authority is prohibited from reselling properties to non-Gullah Geechee buyers.

‘Rich folks want 3,000-square-foot homes’

Bailey and Lotson say zoning that allows larger homes could accelerate the sale of Sapelo properties, both Gullah Geechee-owned and otherwise.

Many homes built in recent decades include enclosed spaces classified as “storage areas” that don’t count as heated-and-cooled square footage. In many instances, Lotson said, those areas are illegally converted to climate-controlled living spaces after the dwelling passes a building inspection.

The new law makes these structures legal — and attractive to wealthy buyers — Lotson and his commission colleague, Harrell, said.

“The size argument is hogwash,” Lotson said. “Rich folks want 3,000-square-foot homes.”

So, too, might investors. Sapelo allows short-term vacation rentals, and Airbnb currently lists nine island properties as nightly rentals. Bigger homes mean more beds and higher occupancy — and more potential revenue for property owners.

Bailey fears the zoning change will embolden those who see Sapelo as a financial opportunity.

“We’ve already seen it with new residents who buy and come here with a sense of entitlement. They don’t want to hear the word ‘no,’ especially from African Americans, people they think they’re better than,” Bailey said. “The zoning change only adds to that and I think will create another Gullah Geechee land sale.”

Following Tuesday’s meeting, Hog Hammock’s Gullah Geechee residents vowed to fight on. They talked of protests, mobilizing a broader public and media outcry, even lawsuits. Their ferry ride home may have been a quiet one, but they aren’t resigned to the zoning change result.

“This,” Lotson said, “is not going away.”

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured