Biden plan could aid Atlanta neighborhoods scarred by highways

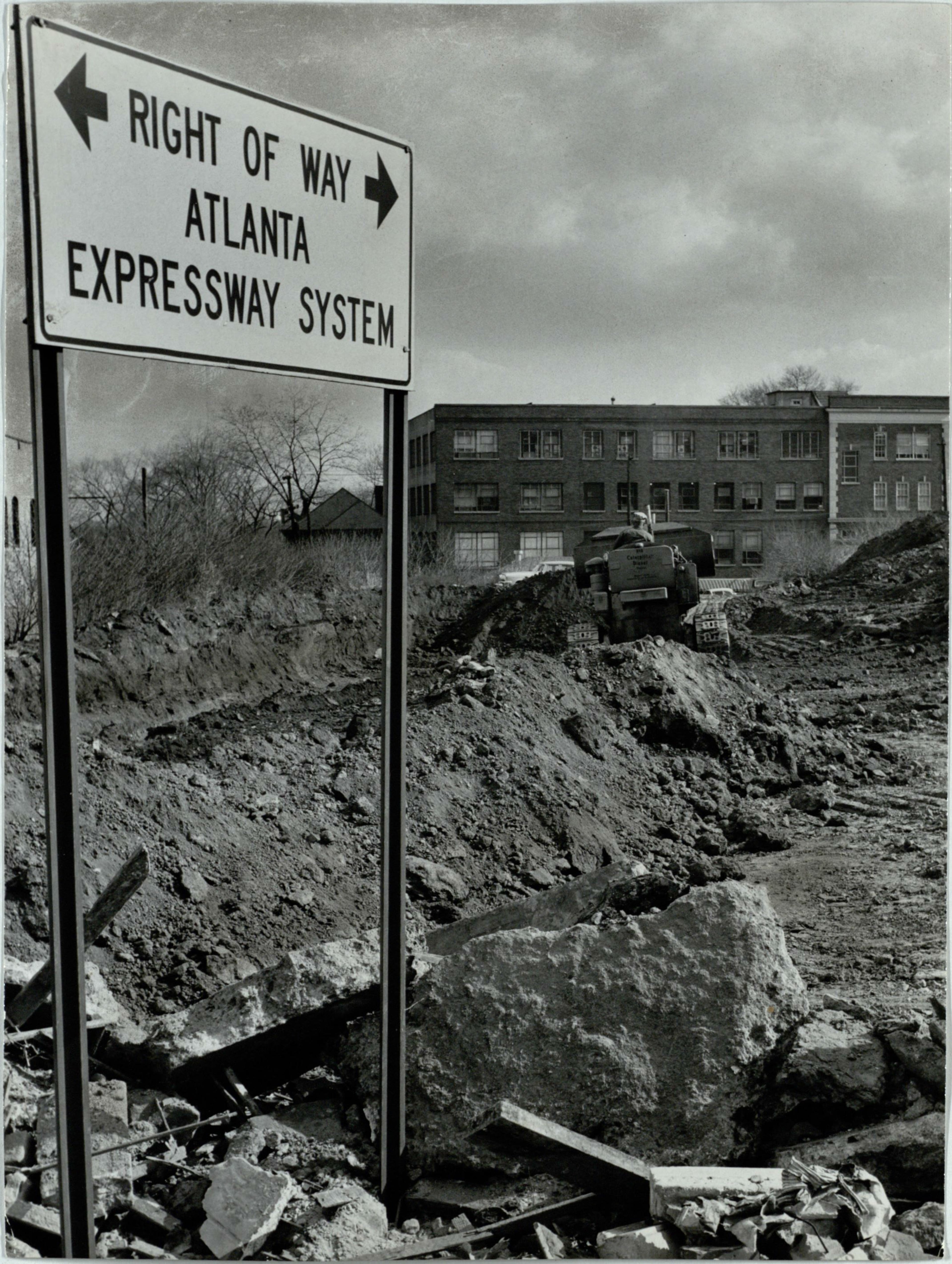

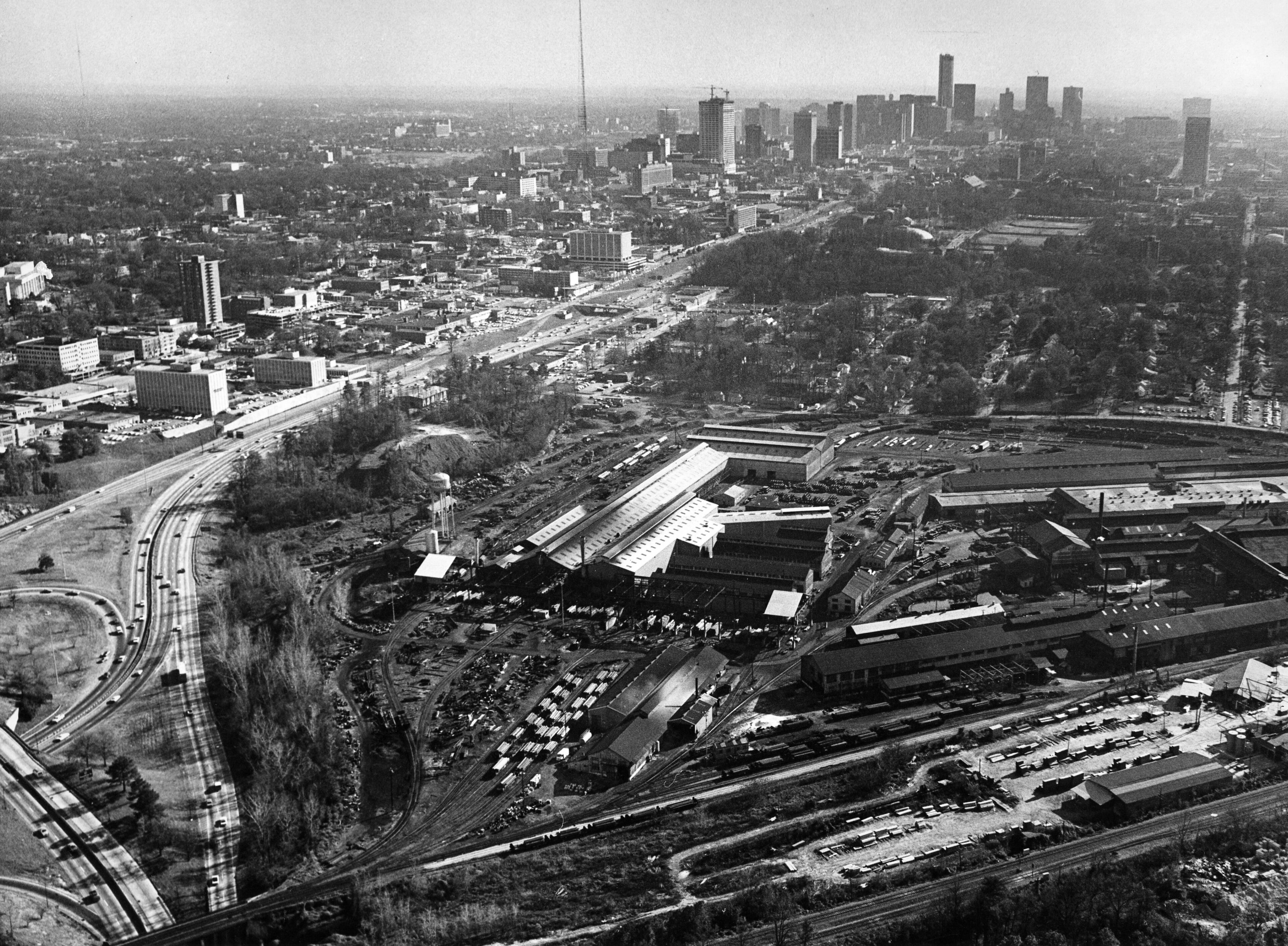

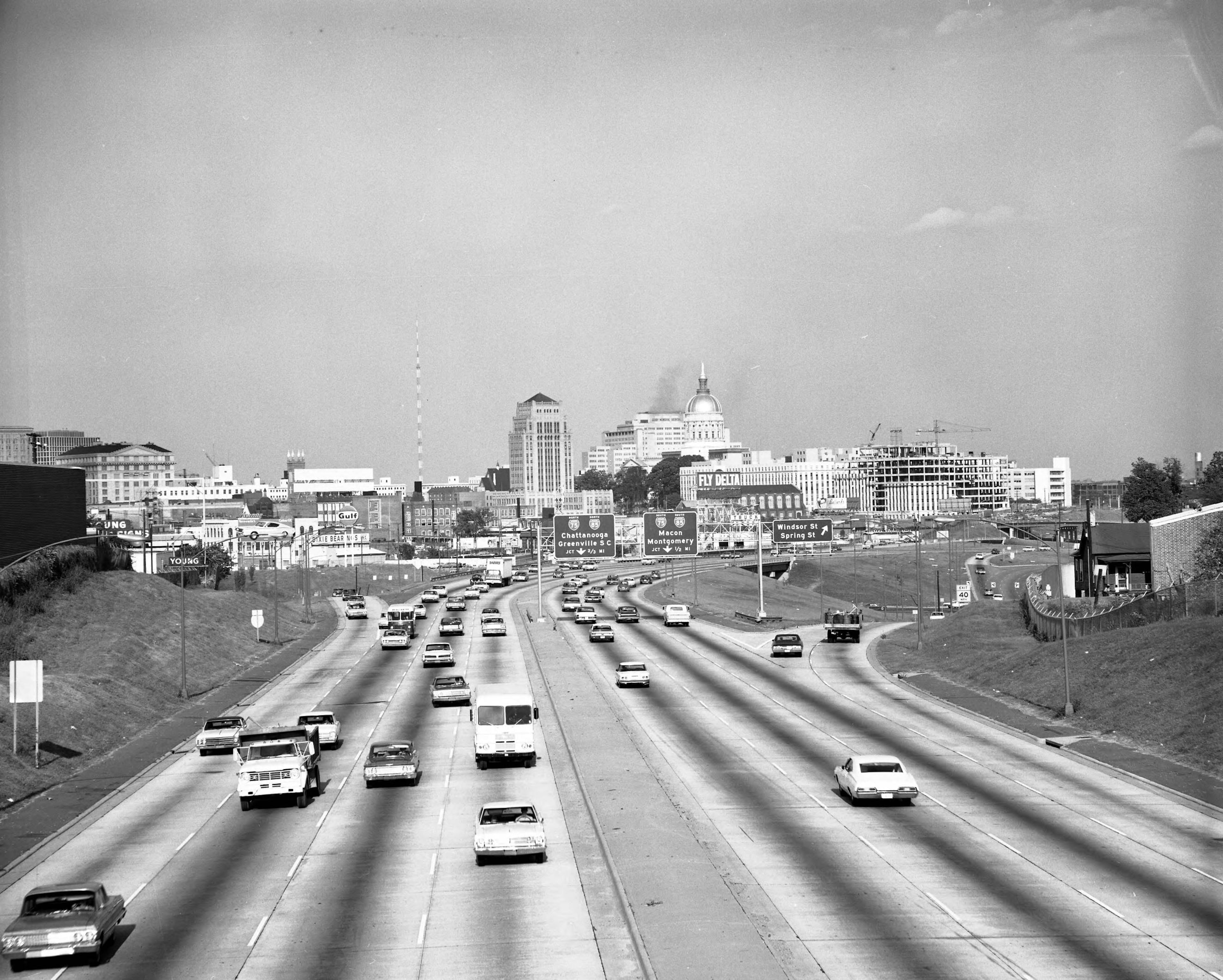

In the 1950s and ’60s, highway construction through the heart of Atlanta leveled homes and businesses, displacing residents and segregating Black neighborhoods from downtown and other parts of the city.

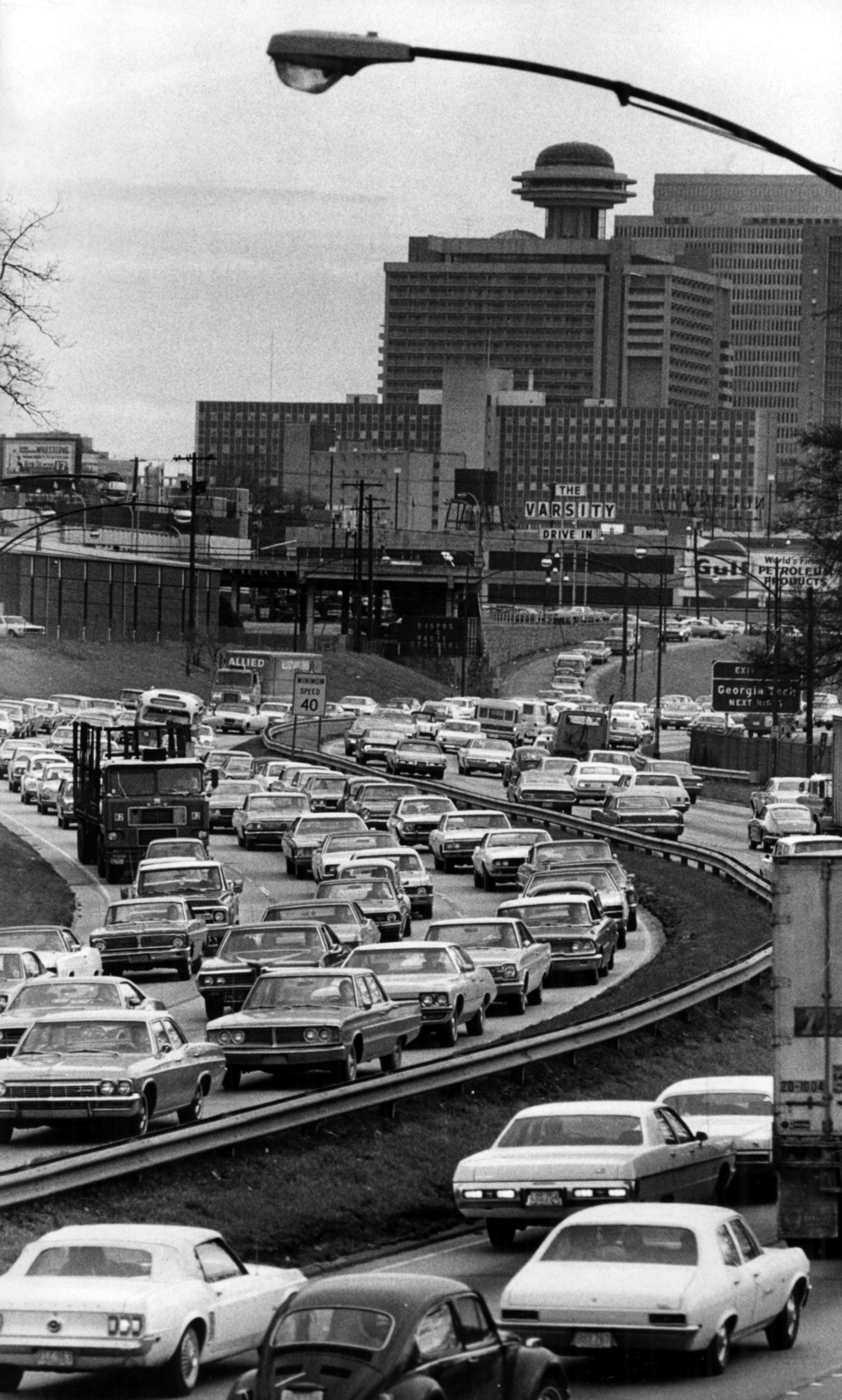

The Downtown Connector and I-20 aided the flight of whites from Atlanta and stranded many Blacks in neighborhoods decimated by the construction. It’s a pattern repeated across the country as interstate highways paid for largely with federal money bisected urban communities.

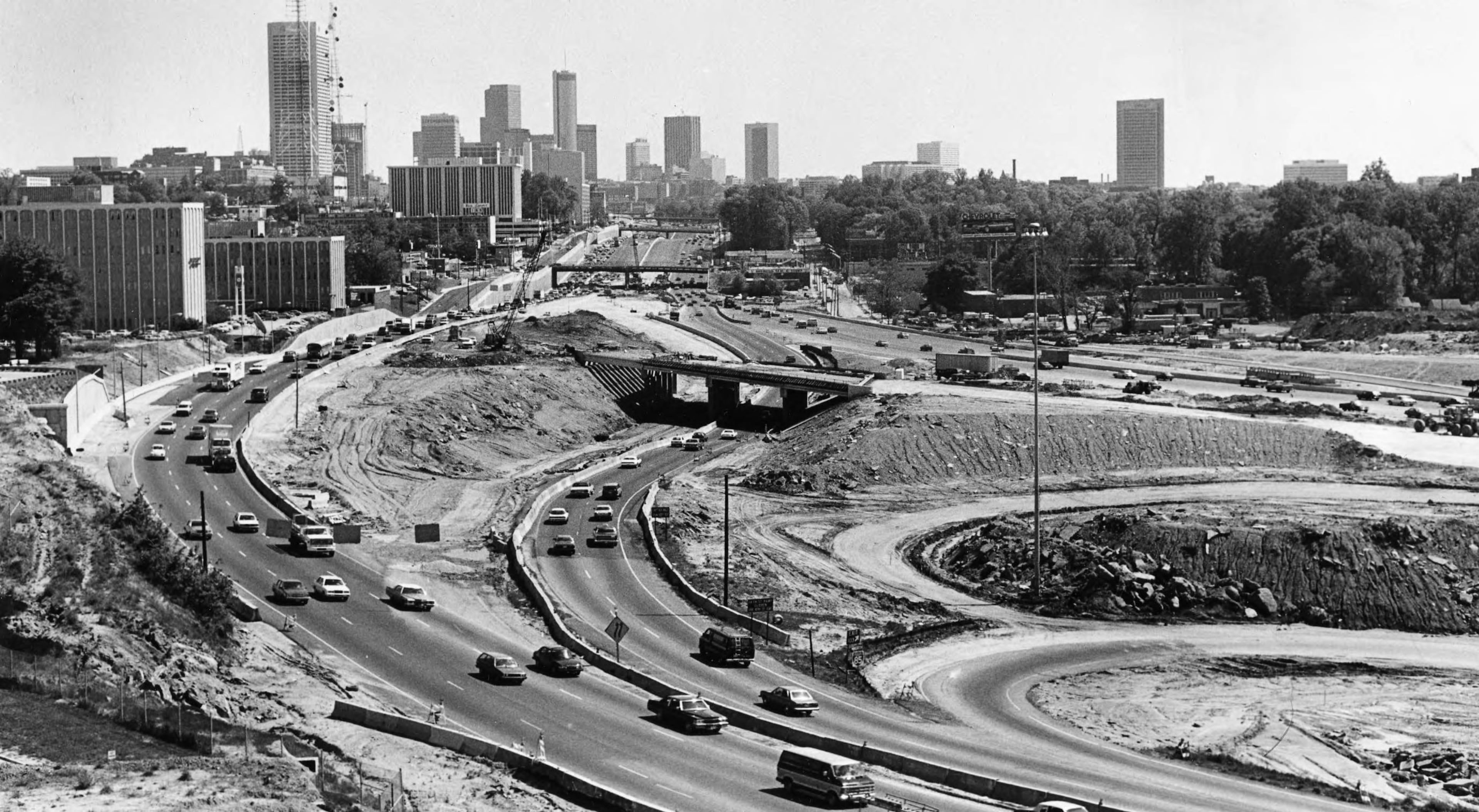

Now President Joe Biden and some Democrats in Congress want to use federal funding to remedy problems caused by that long-ago construction. Some of that money could find its way to Atlanta.

“I can’t stress enough how brilliant this is,” said Tanya Washington, a Georgia State University law professor who lives in Peoplestown near the Downtown Connector. “We’re not just moving forward. We’re actually going to correct some of the things that were done in the past.”

Biden’s plan is short on specifics. Critics say it could produce unintended consequences such as more traffic congestion in local neighborhoods — especially if it leads to closing or significantly altering highways, as some cities are contemplating.

“If you make it harder to get around central Atlanta, you’ll have more people moving to distant suburbs,” said Randal O’Toole, a senior fellow at the libertarian Cato Institute.

Biden wants to spend $2.3 trillion for roads, transit, broadband and other infrastructure initiatives. Tucked in amid larger pots of money is $20 billion to “reconnect neighborhoods cut off by historic investments (in infrastructure)” and to ensure new projects advance racial and environmental justice.

U.S. Rep. Nikema Williams, D-Atlanta, has sponsored a separate bill that would provide an additional $15 billion over five years to address problems caused by highway construction. The money could be used to study the removal or retrofitting of infrastructure barriers, to support transportation and economic development planning and to pay for other initiatives that Williams said could undo some of the harm caused by highway construction.

“These interstates led to the demolition of schools, homes, churches,” she said. “These interstates were put right through the middle of communities.”

Atlanta’s Downtown Connector and I-20 are prime examples. Both highways plowed through existing neighborhoods, displacing minority and low-income residents. That was no accident.

“Atlanta used its highway development to clear slums and Blacks out of downtown areas,” a 1988 Georgia Tech study published in the Journal of Urban History found. “For much the same reasons that civic centers, stadiums, hotels and office buildings were built in or near downtown in cleared slum sections, highway construction was used to remove Blacks from certain sections surrounding the central business district, set up racial buffers and allow the city to redevelop the area commercially.”

Catherine Ross, a transportation planning expert at Georgia Tech, said some of the consequences linger today in neighborhoods adjoining the highways. They include a lack of retail and grocery stores, poor transportation and health problems such as asthma.

“When you run a major interstate through the heart of a city, it’s obviously disruptive,” she said.

Some cities, such as Syracuse, N.Y., want to tear down portions of urban highways, restore old street grids and redevelop neighborhoods. O’Toole is skeptical, saying highway demolition could increase traffic congestion in local neighborhoods and lead to other unintended consequences.

“I’m afraid what we’re going to see with this $20 billion is anti-road people tearing out roads,” O’Toole said.

So far, no one is suggesting that will happen in Atlanta. But there are proposals to build parks over the Downtown Connector. Williams recently requested nearly $1.2 million in federal funding for one of those projects, “The Stitch,” which would cover the highway between the MARTA Civic Center station and Piedmont Road.

“I think our communities are trying to figure out how to reconnect, and have had some success,” said A.J. Robinson, president of Central Atlanta Progress, which proposed The Stitch. “We just need more connections.”

Short of tearing down or covering highways, Williams said projects such as redesigned highway ramps or new green spaces could improve local neighborhoods. She said local residents should have a big say in whatever happens.

The prospects for Biden’s infrastructure plan are uncertain. Republicans have objected to the size of the plan and to its broad definition of “infrastructure,” which includes renewable energy, energy efficiency and other initiatives that go beyond road and bridge construction.

“While details of what they consider infrastructure — and I use that term loosely — are not finalized, it does not inspire confidence that the Democrats are already turning away from regular order, which requires bipartisanship, to get the bill through Congress,” U.S. Rep. Rick Allen, R-Evans, said recently.

With Democrats in charge of the Senate and House of Representatives, Williams believes the damage done by highway construction will be addressed.

“We won’t go into every community saying highways will be torn down,” she said. “We have to look at what’s best for each community.”