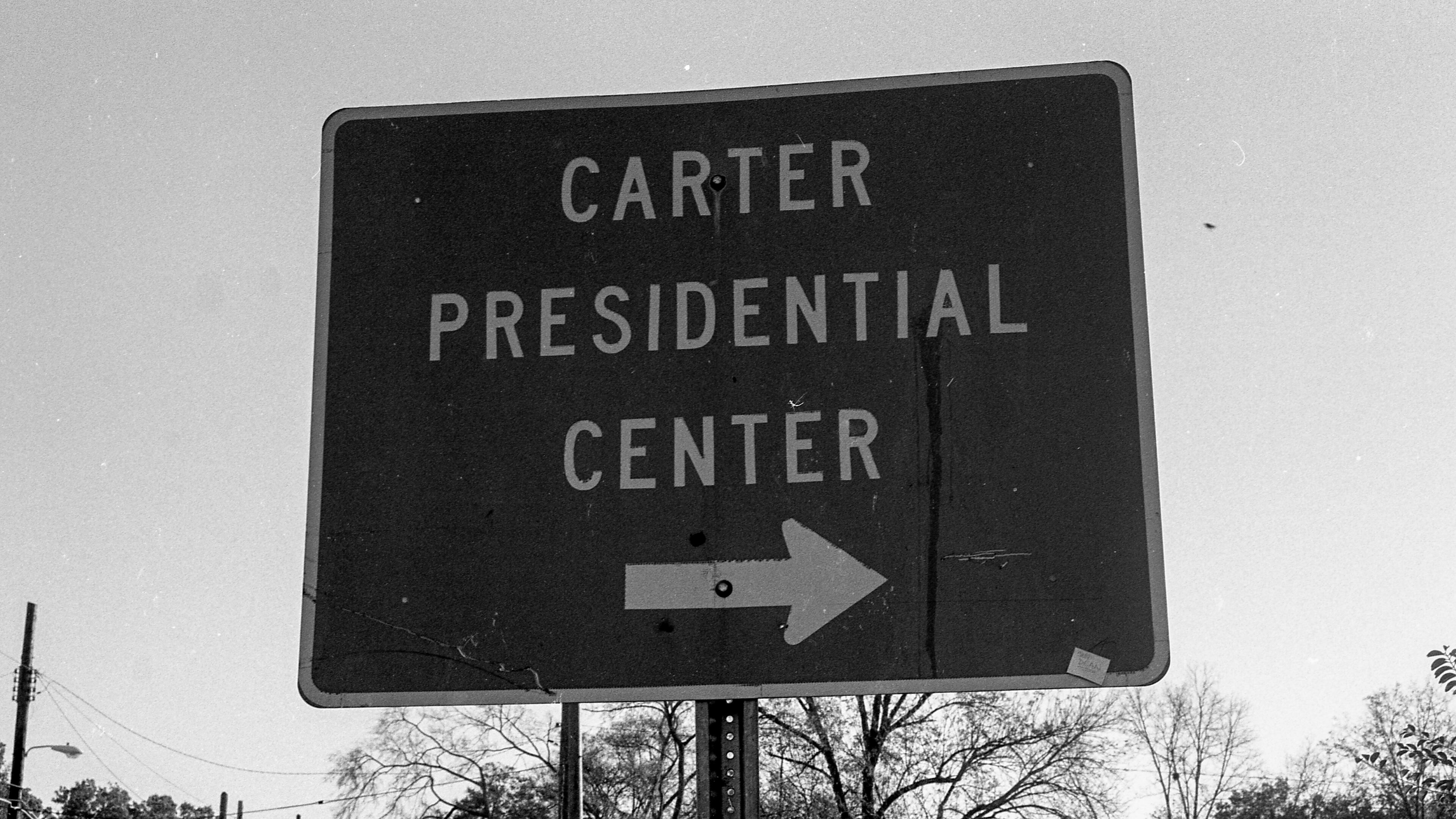

The road to the Carter Center

Former President Jimmy Carter, who died Dec. 29 at 100, was a saint abroad, but he had a more complicated legacy at home. Though the Carter Center and Presidential Library has been a celebrated base of operations for international diplomacy and disease eradication, it is worth remembering the controversies that surrounded its construction.

Earlier highway planning efforts by the state of Georgia led to the demolition of significant portions of several historic neighborhoods, and the later selection of this site for the Carter Center alongside a revised version of the proposed highway galvanized local opposition to what was simply referred to by residents as “The Road.”

I attended the former Henry Grady High School from 1988 to 1992 and studied photography there with George Mitchell, who was then a photographer for The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. To complete his class in 1990, I undertook a photo essay that documented the destruction of sections of the Old 4th Ward, Inman Park, Little Five Points, Poncey-Highland and Candler Park.

The road went straight through my childhood. The path of flattened structures ran behind Mary Lin Elementary — where I attended first through sixth grades — and was visible during recess. It came within a block and a half of the house on Washita Avenue where, as a teenager, I used to babysit Jon Ossoff, now a U.S. senator, and where Rep. John Lewis was an occasional guest at the annual Fourth of July cookout. It continued past my father’s business, Design & Cabinetry, on the corner of Elizabeth Street and Bernina Avenue.

Construction languished for more than a decade, but the damage had been done. I grew up playing in the kudzu-covered fields full of stairs that went nowhere and half-built highway overpasses. One of the biggest of these was right behind my dad’s shop and bore a striking resemblance to Stonehenge. It has now been absorbed into the Beltline Trail.

Eventually, compromises were reached. First, the Carter Center and then the Freedom Parkway were built, and the landscaping of adjoining Freedom Park buried the last foundational outlines of the families and residences that had once occupied the same place. The subsequent reinvigoration of the affected neighborhoods may feel like a successful story of urban renewal, but the ghosts remain.

While home from college one summer, a friend and I sneaked onto the grounds of the Carter Center after midnight and sat in the Japanese Garden with its beautiful hilltop view of downtown Atlanta. It was familiar and foreign all at once. We just stared and silently reminisced. The guard eventually found us. “Move on” he said.

Jimmy Carter spent much of his life helping people and followed his religious convictions, but even saints are human, and their decisions can have varied consequences.

The road to the Carter Center was paved with good intentions, but it left many feeling less than blessed.

Jeremy Fletcher grew up in Candler Park, Atlanta. His mother taught art history at Emory University and his father ran Design & Cabinetry near Inman Park. He attended Mary Lin Elementary School, Inman Middle School and Grady High School. He lives in Teaneck, New Jersey, where he is a band director and professional jazz arranger and continues to pursue photography.