The average American moves about a dozen times. With each move comes a chance for an audit. Are we downsizing or expanding? Is it time for a new couch? Should we refurbish great-grandma’s old china cabinet?

Just as moving is an important yet rare event, U.S. tax policy often operates the same way. There have been only 15 significant tax reforms since 1940, but, come 2025, President-elect Donald Trump and an incoming Republican majority in both houses of Congress will have to reform our tax code again when Trump’s 2017 tax cuts expire.

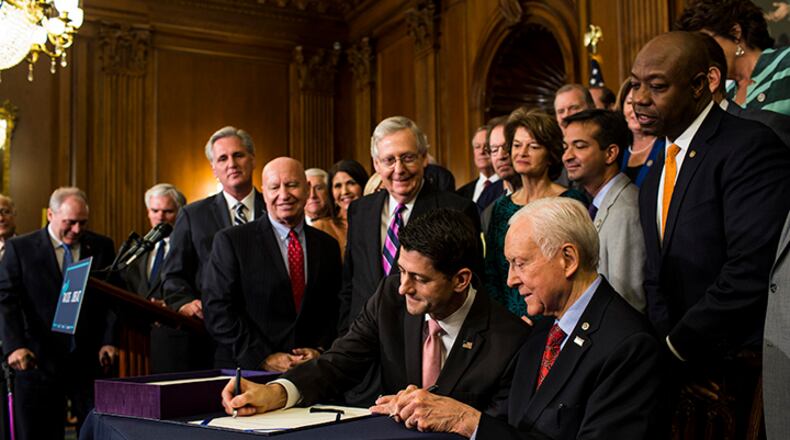

Credit: Handout

Credit: Handout

As we prepare for the tax code’s “move,” it’s time to start cleaning out the proverbial attic of our messy system.

Before we decide what should stay and what should go in the tax code, let’s first look at what house we moved to in 2017.

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act was a generational rewrite of our tax code. It lowered income tax rates, increased the standard deduction, doubled the child tax credit, drastically reduced corporate tax rates and transformed how we tax multinational corporations. All the changes had to fit within a 10-year budget window, and, to comply with those requirements, many of the corporate provisions were made permanent while the individual tax cuts were put on a path to expire, or “sunset.”

The goal of the tax law, according to its advocates, was to boost economic growth, simplify the tax code and make us more competitive against other countries. Though all were achieved to varying degrees, to say the global economy has changed drastically since then would be an understatement. Our workforce looks different, the economy is still feeling the lingering effects of the pandemic and countries across the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development have also cut taxes (or, in some cases, increased them on U.S. companies that buy and sell overseas).

And despite its achievements in making tax filing simpler for most workers, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act left us with a complicated tax system, which has only gotten more complicated in the Biden era.

Republicans have offered mixed signals on where they want to move. In Congress, 73 House Republicans have endorsed staying put, saying we should make the TCJA permanent. On the campaign trail, Trump called for extending it but repealing some of its biggest pay-fors, including the $10,000 cap placed on state and local tax deductions, something many Republicans oppose.

In other words, there is not yet a clear consensus. Instead of a blanket approach, we should take stock of each provision and decide what should go, what should stay and what should be reformed.

First, let’s decide where we want to live. Growth, simplicity and neutrality should be the bedrock of any tax code, and many features of the TCJA achieved that. The corporate rate is now much more competitive, so calls to reverse that should be off the table. The law’s provisions for individuals and families resulted in higher after-tax incomes for many while simplifying the tax filing process by making the standard deduction more valuable than itemizing.

Next, we should be honest about what worked and what didn’t in the TCJA. The law made great strides toward improving the treatment of business investment by allowing full expensing — though only temporarily and for only some assets — but it made the treatment of research and development worse. Full expensing for all investment, including R&D, should be made permanent. Full expensing removes barriers that hinder companies’ ability to invest and expand and, if made permanent, would lead to sustained job creation and economic growth.

Third, Congress must declutter by removing the most complicated additions to the tax code, including preferential energy credits and a new corporate minimum tax superstructure that found their way into the tax code two years ago.

And policymakers must decide how long they want to live in this new home. For the sake of the economy, we should be aiming for the long game; therefore, it’s crucial to contend with how these tax changes affect our multitrillion-dollar deficits and how they will grow the economy. Full expensing and neutral corporate policies generate a good amount of growth relative to their costs. But if we want to continue to pay down our debts while remaining globally competitive, lawmakers should go further — on the individual side and on the corporate side. Unnecessary preferences, including the state and local tax deduction, should be eliminated entirely. Business taxation is still a mess, with separate regimes for corporations, partnerships and sole proprietorships. This is an opportunity for great simplification.

America handed Republicans control of the White House and Congress, and together they will have to decide the future of our tax code. For the sake of our economy, moves toward growth must win the day.

Daniel Bunn is president and chief executive officer of the Tax Foundation in Washington, D.C.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured