TORPY: Inhumanity rules at Georgia’s prisons. But does anyone care?

The conditions in Georgia’s prison system are anything but humane. But the humans involved are convicted criminals, so that largely draws shrugs.

In October, federal investigators released a report that “lays bare the horrific and inhumane conditions” inside Georgia’s prisons.

“Our statewide investigation exposes long-standing, systemic violations stemming from complete indifference and disregard to the safety and security of people Georgia holds in its prisons,” said Assistant Attorney General Kristen Clarke. “People are assaulted, stabbed, raped and killed or left to languish inside facilities that are woefully understaffed.”

Meh, said the state.

“Contrary to (Justice Department’s) allegations, the state of Georgia’s prison system operates in a manner exceeding the requirements of the United States Constitution,” spokesperson Joan Heath said at the time.

Are you listening Gov. Kemp?

The sorry state of Georgia’s prisons is nothing new. The conditions inherent a century ago were made infamous with the book “I Am a Fugitive from a Georgia Chain Gang!”

Last weekend, my colleagues Carrie Teegardin and Danny Robbins released yet another investigative piece about the hellhole that is the Georgia prison system: “State prison system engages in deception as crisis builds.”

The Georgia Department of Correction’s strategy seems to be that if you can’t fix it, then employ prevarication, avoidance and delay. Even to a federal judge.

Dying in a Georgia prison is becoming more common. From 2015 to 2019, the prisons averaged 158 deaths a year. Since 2020, it’s averaged more than 265.

This year, there have been 270 deaths through October, which will certainly pass 2020’s grim record of 281. And that’s without a pandemic raging through the cellblocks, which caused 72 of the deaths then.

A prison spokesperson has said almost half the state’s 50,000 prisoners are doing long stints, so lots of them are simply dying from natural causes.

But a shank in the back or being stomped to death is not natural.

Last year, state prisons had 38 homicides, a record. This year, there have been at least 51.

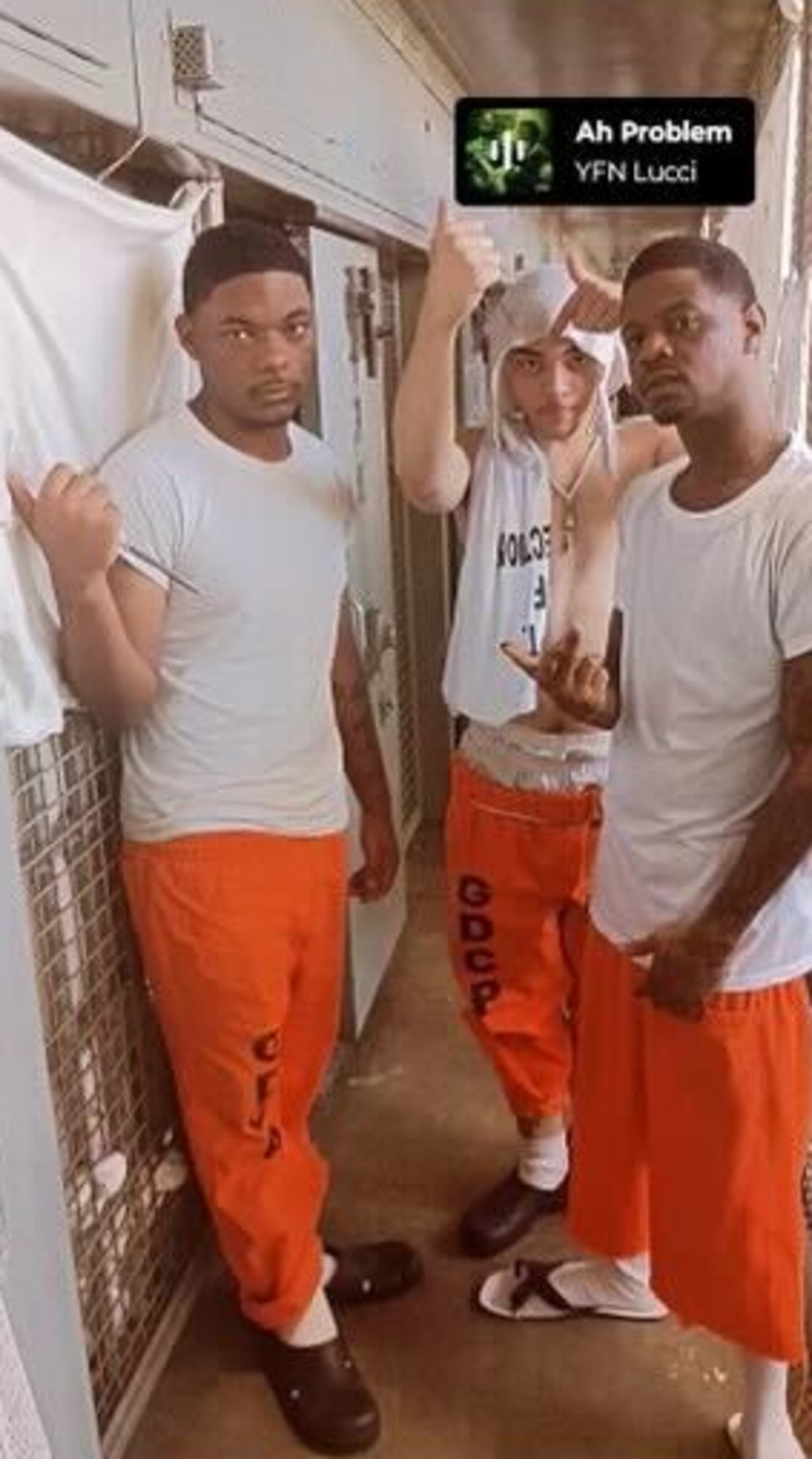

My colleagues have also documented widespread cases of prisoners using illegal cellphones to engage in financial fraud from their cells, or to order attacks outside prison.

Call this a “crisis” and you’ll draw ire from prison Commissioner Tyrone Oliver. In August, he told a state Senate committee that news articles about prison conditions are simply “propaganda.”

And why not? Don’t like what you’re hearing? Call it “fake news.”

The Senate committee, which has met since August, is making recommendations to increase prison guards’ salaries, improve mental health services and move prisoners to single cells to increase safety.

The first recommendation underlies a key ingredient of what has caused the ongoing crisis.

Decades ago, rural communities lobbied state officials to get prisons located there because they provided solid jobs. Increasingly, though, no one wants to be a prison guard.

In October, a DOC list of vacancy rates for correctional officers listed 57 correctional facilities, with 25 counted as “state prisons,” largely those that house the most troublesome inmates.

Of those 25 facilities, 15 have guard vacancy rates of 65% or more. That leaves the prisons vastly understaffed, meaning the gangs easily take control.

“Right now, they are running the prisons,” said Wright Barksdale, the district attorney of the Ocmulgee district in Middle Georgia. His circuit has eight counties and three prisons. They keep him busy.

He said he has 18 homicide cases pending in his circuit. Ten came from prisons.

Sometimes, the criminal calendar in Hancock County’s courtroom is filled with state prisoners accused of new crimes. Hancock is listed as being short three of every four guards it needs to operate. Baldwin, one of his other prisons, is about the same.

Not long ago, his office put a man in prison on drug charges. “We sentenced him to a death sentence,” Barksdale said.

The man was killed in prison.

“It’s unbelievable how dangerous it is,” the DA told me. “Right now the inmates have no fear of the DOC. They own the DOC.”

Years ago, correctional officer jobs were sought after. “But now,” he said, “if you can go to a pest control job and spray for bugs, not have to work weekends and not have to worry about getting stabbed, which job would you take?”

I’d call Orkin.

Barksdale is frustrated. He says the state is dumping its responsibility on to prosecutors like him in rural districts that are already struggling. Starting next year, he said, he’s going to use a state law that allows him to bill the state for prosecuting inmates who have committed crimes in prison.

He noted the state has a huge pile of taxpayer cash reserves sitting around — it’s about $16.5 billion.

“If you have a rainy-day fund, then what is it for?” he asked.

Last year’s prison budget was almost $1.5 billion. But spending on prisons has always lagged. Ten years ago, it was about $1.2 billion.

“I’m a Republican and a conservative, but I’ve never been shy of saying what is right and what is wrong,” he said. “These are human beings. They need to be safe when they are incarcerated.”

Brian Kemp, are you listening?