TORPY: A tale of two failed transit votes. Or, ‘I’d rather just drive’

The old suburban white flight counties of Cobb and Gwinnett are now voting solidly blue and are increasingly crowded.

So it seemed it might be time to finally create some real transit systems to match their urbanization.

The thought this year was that highways are clogged and voters, who now are of many hues and ethnicities, might think differently from those of the past. This time, the thinking went, residents might agree to tax themselves (a 1-cent sales tax over 30 years) and create sprawling transit systems to make their counties more accessible to all residents.

And maybe shorten godawful commutes.

Nope.

Although Kamala Harris won decisively in both counties — getting 57% of the vote in Cobb and 58% in Gwinnett — the transit plans fell way short of those totals.

The Cobb plan went down in flames, losing 62% to 38%.

Gwinnett’s fared better, but still lost by 7 points, 53.5% to 46.5%.

The Gwinnett plan, which could have raised up to $17 billion over 30 years, seemed more winnable than Cobb’s, which could have raised more than $10 billion.

Part of that optimism was that, in 2020, a transit referendum in Gwinnett lost by just 1,000 votes out of nearly 400,000 cast. It was a far cry from the raw and racially divisive vote there in 1990. Back then, the population was 90% white. It lost 70-30.

Today, Gwinnett is a far different place, with a population of nearly 1 million residents (there were 352,000 in 1990) and it is now 31% African American, 30% white, 23% Hispanic and 14% Asian.

It didn’t really matter. It was a racially diverse coalition of “No” votes.

Cobb is whiter than Gwinnett — 48% — which I believe drove the higher “No” vote.

Commissioner Jasper Watkins, who represents southeast Gwinnett with a large Black population and many subdivisions of single-family homes, said the vote “was truly not a partisan issue. It was socio-economic. The environment was toxic for any kind of tax.”

Most of the precincts in his district voted against it. Residents weren’t voting black and white. The were voting green.

Gwinnett honed its current proposal from past failures:

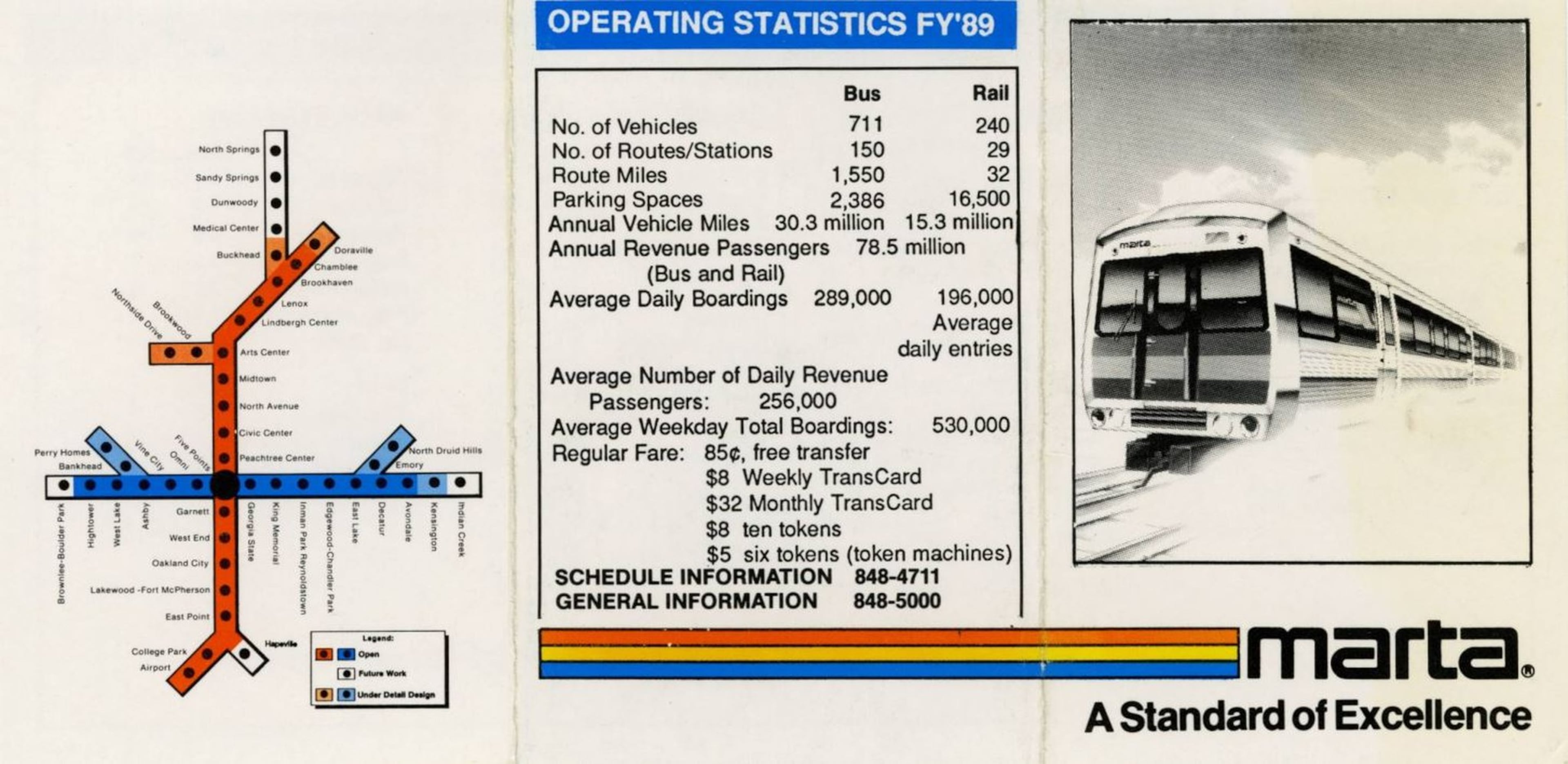

— “MARTA” carries a bad connotation with suburban voters? OK, we’ll do our own system.

— Heavy rail is costly (and would connect to MARTA’s)? Well, then, let’s lose that option.

— Gwinnett is more diverse? Let’s have plans explained in Spanish.

— Much of the county is single family and not dense enough for transit? We’ll have “micro-transit,” which is kind of like government-run Uber.

“They were jumping through hoops to get everyone served,” said Emory Morsberger, who runs the Gateway85 Community Improvement District, a self taxing area on I-85 on the county’s west side. Those were largely the precincts that supported it.

The plan tried to give a little of everything to everybody. And in the end, they ended up with nothing.

Ultimately, it came down to an age-old question: What’s in it for me?

Morsberger summed up the feeling: “If I don’t need it, I don’t want to pay for it.”

It’s true Gwinnett has changed, he said. “We have lost a lot of the people who didn’t want a connection to Atlanta. They’re either dead or have moved on.”

But they’ve been replaced by new residents who have the same feeling about transit for a different reason. He noted that minority residents (now a large majority in the county) “moved up and out” to Gwinnett. “They’re living the suburban dream and that doesn’t include a bus on your street.

“A lot of people who moved here to single-family homes opposed it,” Morsberger said. “In Snellville, if you have two cars in the driveway, you’re not going to vote for it.”

Morseberger said he’s exploring the idea of creating a “special purpose tax district” to bolster the existing transit plan. (There is limited service funded by property taxes and grants.)

“I’m tired of repeating this and expecting a different result,” he said.

Commissioner Matthew Holtkamp, the commission’s sole Republican and the board’s outlier in opposition to the plan, said the proposal was asking for just too much money for an uncertain future in the transit world.

In fact, transit ridership has been dropping in cities across the nation over the past two decades for numerous reasons. He posted a video of him riding an empty Gwinnett bus.

It seemed to catch the mood of unhappy voters.

In Cobb, transit supporter Matt Stigall sang a familiar tune, saying there was an anti-tax mood with voters and a bubbling feeling that the plan was “transit for others.”

He said the initiative wasn’t well publicized or explained and often drew blank stares from voters. Plus the legalese wording, “Shall a special 1 percent sales and use tax be imposed...” sure didn’t help the effort.

Cobb had more organized opposition than Gwinnett, including Republican school board Chairman Randy Scamihorn, who used his taxpayer-funded bully pulpit to rail against the plan.

In a couple of missives, he said the vote would “negatively impact our schools” and “increase the transience of students and families from the metro, into and out of Cobb.”

It had the ring of arguments from another decade.

Because the past is never really gone.