OPINION: The Dixie Mafia and the enduring tales of murder

The allure of true crime stories is puzzling. Americans overwhelmingly demand that their government reduces crime. But, at the same time, they devour the grisly and gruesome in books, movies and podcasts.

I say this as my wife and I binge-watch “Ozark.”

Crime stories are a guilty pleasure, allowing us to tap into primordial fear from the comfort of our living rooms.

I got to thinking about this after reading an outstanding crime tale about legendary Dixie Mafia killer Billy Sunday Birt spun by my colleague, Bo Emerson.

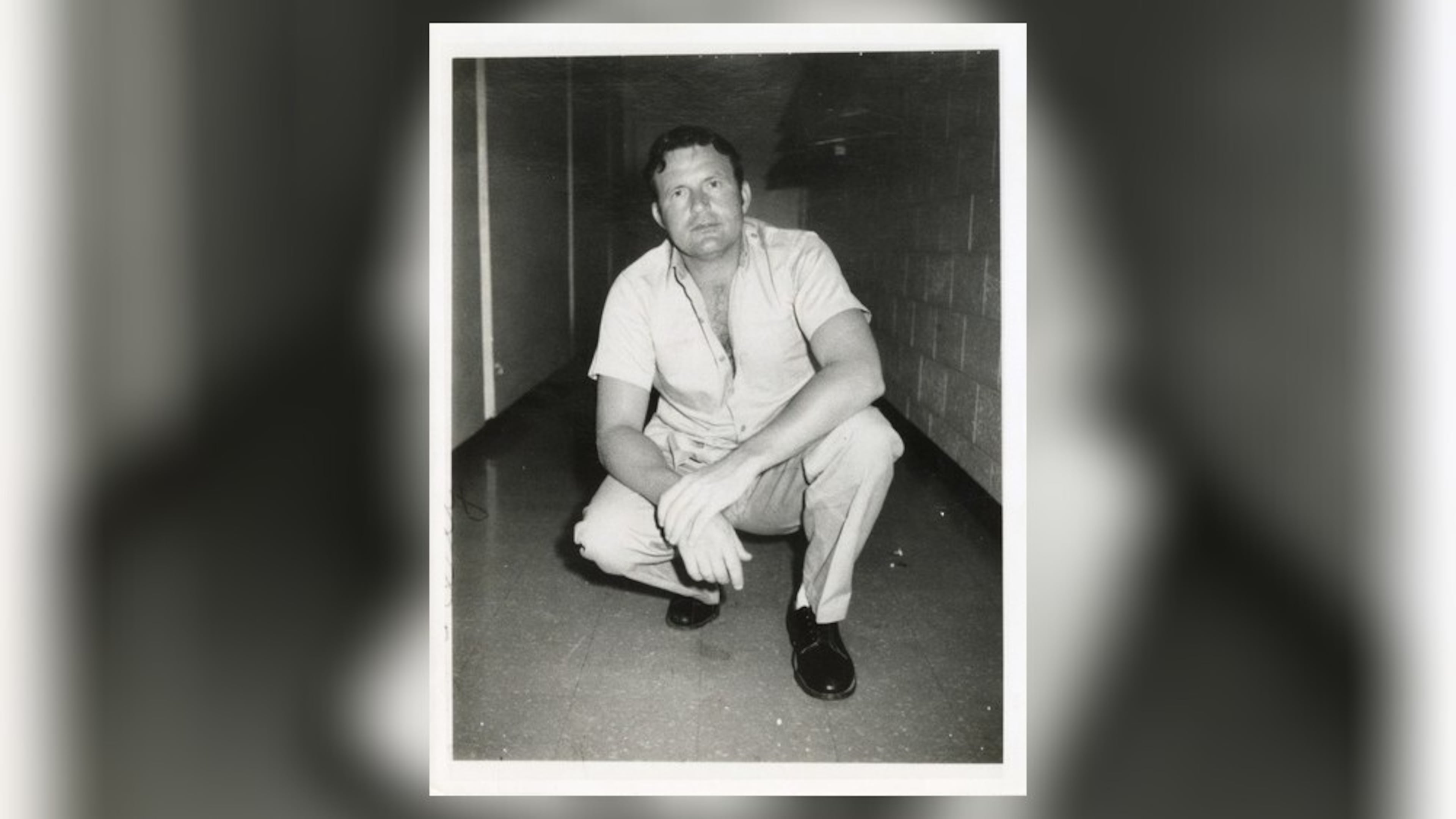

Birt, named after Billy Sunday, the early 1900s evangelist, is thought to have murdered more than 50 people — some for business, some for passion — and then burying them throughout northeast Georgia.

Bo dug into the story after learning how Birt’s family is divided concerning his legacy. One son, Stoney, self-published a book about his father and was featured in the 2020 podcast “In the Red Clay.” He even opened a distillery in the family’s hometown of Winder, a business that honored his murderous dad. The distillery did well but is now shuttered because of a legal dispute.

“He had more morals and a code of honor that no preacher or politician that I’ve ever known could stand up to,” Stoney told my colleague. That is, when he wasn’t choking to death an elderly woman with a clothes hanger or killing witnesses to his prolific crime sprees.

Stoney’s brother, Shane, is writing his own book. He called his father’s shadow “a curse” and said there’s no way around it — his daddy was evil incarnate.

Birt, considered Georgia’s most prolific killer, was a real-life boogeyman. Mention of his name instilled terror and silence in the 1960s and early 1970s. Even though he was sent to prison for life in 1974 and hanged himself in 2017, his wake still ripples.

Earlier this year, while researching his book, Shane Birt and retired GBI agent Bob Ingram, who put his dad in prison, connected Billy Sunday Birt and three others to a 1972 triple murder of a North Carolina car dealer, his wife and son.

The one surviving member of the murder crew, now 81 and still in prison, ‘fessed up.

Retired FBI agent Ronnie Webb, who worked for the GBI in the early 1970s, solved a couple of murder cases connected to Birt.

“I worked the Mob most of my career in the FBI, but he was the worst I’ve seen; he was a true sociopath, no remorse,” Webb told me. “Mob guys did it for business. Some of them liked to kill, but not like Billy. He really liked to kill.”

Once, Webb and other lawmen tried to prevail on Birt to give up the location of one of his victims’ bodies. The family could give the man a decent burial, they said.

“What are you talking about?” Birt responded, annoyed. “I gave him a decent burial.”

The so-called Dixie Mafia is a crime wave from another place, another time. It was born from extreme poverty (a familiar theme), where desperate folk brewed moonshine to eke out a living. Birt didn’t brew moonshine; that was hard work. Instead, he drove fast cars and delivered the product to retailers.

“But the government cut into their business,” Webb said, explaining that moonshine business dried up when northeast Georgia counties went wet.

So, the outlaws had to diversify.

Northeast Georgia became a haven for chop shops, robbing crews and safe-crackers and, of course, drug trafficking. “It was a natural progression from moonshining to drugs,” Webb said.

The “Dixie Mafia” had no real hierarchy like the Mob; it was a loose configuration of thugs and ne’er-do-wells who carved out their illicit niches and banded together when crimes needed committing. Aging Dixie Mafia criminals whom I contacted years ago denied the existence of such an organization, calling it a tale dreamed up by law enforcement.

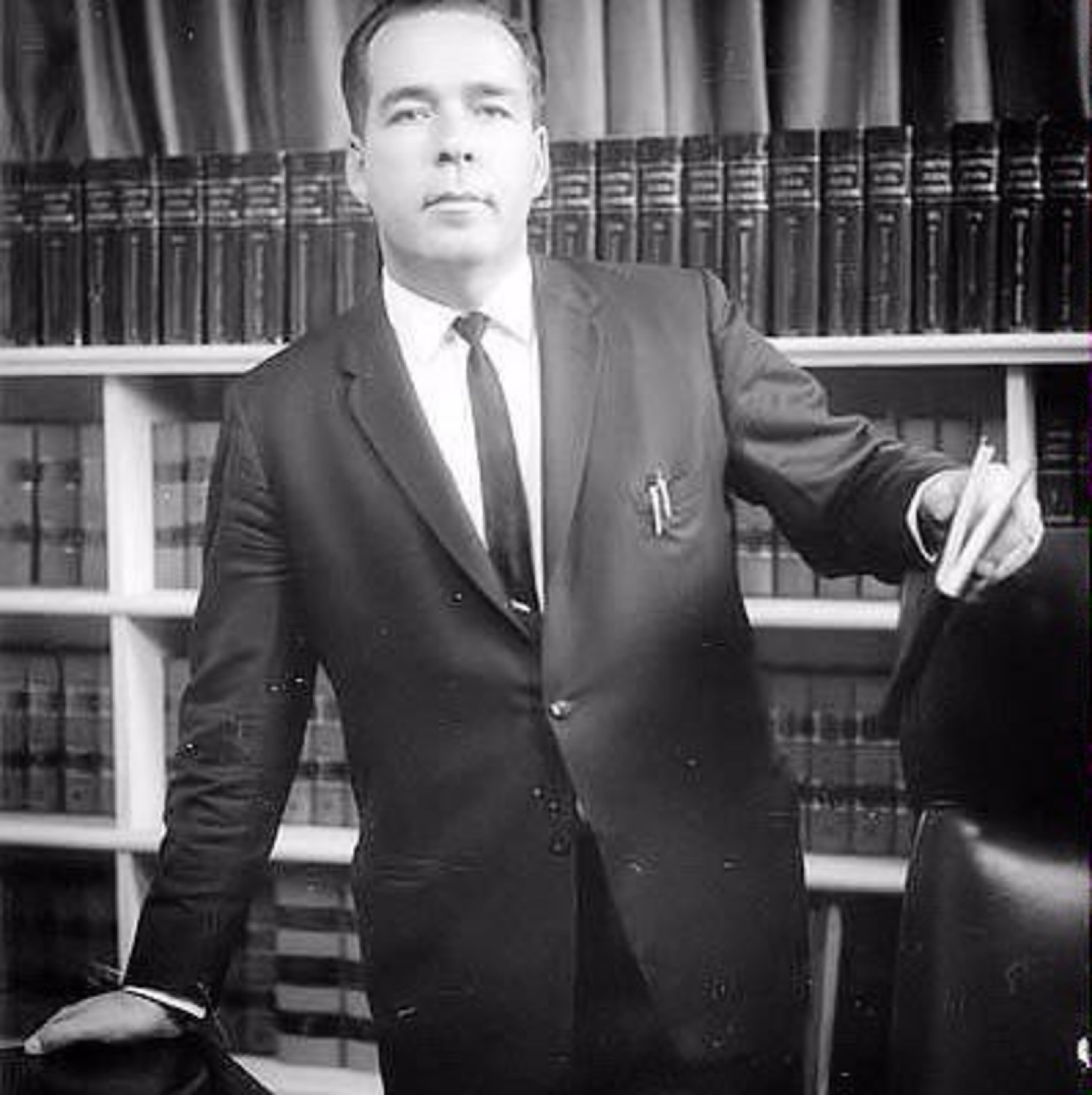

But the region where they operated was so corrupt that Floyd Hoard, the crusading prosecutor of Jackson County, was blown up in 1967 by dynamite planted in his car outside his home.

In 2001, I wrote to Birt, trying to interview him about the Dixie Mafia. He politely declined. “I’m not big on talking,” he responded.

At the time, one of the old hoodlums from his era, a safe-cracker named Daniel Warren, had driven down to Molena, a small town an hour south of Atlanta, and committed a double shotgun murder during a robbery. Oddly, Warren had recently been released after serving 35 years for kidnapping a banker and his family to rob a bank — in that same town!

I wrote a story about Warren and the tales such desperadoes inspired. One, told to me by three separate retired GBI agents, had Warren and an accomplice handcuffing the sole patrolman of a small South Georgia town and ransacking a train and the town’s businesses.

Another was him and another inmate welding themselves inside a firetruck’s water tank to escape prison. They were supposedly caught.

In a letter, Warren called my story “cute,” even adding a smiley face. But, he added, it was untrue: He was in solitary confinement during the escape attempt.

“I was in lock-up for having a sawed-off shotgun,” he wrote.

And the tales live on.