Forty years ago this month, I nervously stepped into a dumpy brick building in Southern Illinois and started my newspaper career.

I had been hired by The Daily American in West Frankfort, a shrinking coal mining burg of 9,500 residents, to cover City Hall and whatever else happened around there. I earned $165 a week.

The editor glanced up, handed me a notebook and told me to head to the police and fire stations to get the overnight doings. I walked to the P.D. and was met by a sputtering chief angrily telling me he would not release any reports because the paper wrote something he didn’t like.

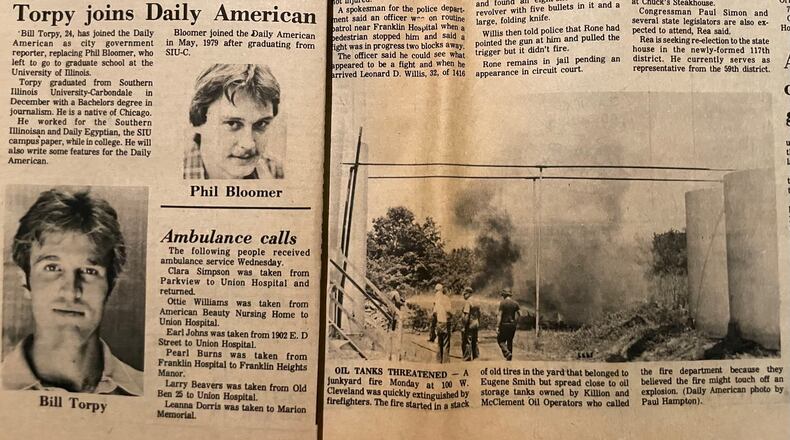

I shrugged, gulped and wandered next door to the fire department where I discovered Breaking News!!! A trash fire had spread and threatened some nearby oil storage tanks. I interviewed the participants and excitedly returned to the newsroom to write up a saga rivaling the script of “Towering Inferno.” Instead, I was told to bang out a paragraph to run as a caption under a photo of the fire. My new boss also informed me that “extinguish” has an “x,” not an “s.”

The three years at that paper was an astounding plunge into community news: Writing about city budgets, coal mining, drug busts, poverty, tempestuous personalities and weird stuff. Once, the dog catcher was so angry that we ran a photo of a dog looting a garbage can that he came to the paper, ordered me outside — I thought he wanted to fight — and opened the trunk of his sedan to show me a trunk full of stray dogs he had shot. It was his way of saying he was doing his job. Later, I learned in a police report that he bit off part of a man’s ear in a bar fight.

Like I said, real community journalism.

The Daily American is no more. The closing of the coal mines crippled the town’s economy and the paper’s revenue and readership dried up. The chain that bought it after I worked there saw no future and shuttered the century-old paper, adding West Frankfort to the “news desert” spreading across rural and small town America — that is, areas that no longer have a hometown source of news.

My second stop in journalism, the Daily Southtown in Chicago, a once-scrappy paper, is now a husk owned by the Chicago Tribune, which once called itself “The World’s Greatest Newspaper.” In the past decade, The Trib has gone through bankruptcy and has been gobbled up by a vulture hedge fund.

Credit: AJC

Credit: AJC

Such is the state of the newspaper industry which has been savaged by the implosion of advertising and circulation in the past 20 years. According to Pew Research, Sunday circulation for locally focused newspapers dropped from 28 million in 2015 to 15 million in 2020. Forbes said Sunday circulation in 1990 was 63 million. Revenues, and staffing, have similarly plunged.

I know, some blame the “lame stream media” — I got such an email yesterday — but it was the historical, and inevitable, surge of the Internet that almost instantly caused lucrative classified ad revenue to vanish, while eating away regular advertising and subscriptions. Today, we must do more with less.

Local news is vital because it is reporters living in your town who go to City Hall for answers, dig through court files, attend school board meetings and try to weave an objective sense of life as it happens.

Last week, Northwestern University released a report that said about 2,500 dailies and weekly newspapers have closed since 2005. Less than 6,500 survive. That means towns across the country increasingly have no one watching their public officials or printing graduation photos.

Another report said the big dailies, who are mostly still standing, have lost 80% of their print circulation since 2000. Newspapers are replacing some revenue with money coming from the digital side, although the gain is not restoring the dead tree money as well as we’d like.

Recently, my boss, Kevin Riley, wrote a column touting the wonders of the ePaper, the product subscribers can receive without having to walk to the end of the driveway or dirty their hands with ink. He mentioned the inevitable demise of the printed edition in the industry, although adding the Sunday version should stick around for a good long while.

It’s certainly a tough slog. Printing and delivering words on paper is a 19th century manufacturing process in a digital world.

But there are those who express (guarded) optimism. Take Dink NeSmith, Jr. the retired co-owner of the Athens-based Community Newspapers, Inc., which publishes about 25 small newspapers.

Not long after he retired last year, he heard that the Oglethorpe Echo, a small weekly where he lives, was set to shut down. He called the owner, asked him to donate the soon-to-be-defunct paper to a non-profit foundation he dreamed up and it is now being operated in conjunction with budding journalists from the University of Georgia. It’s a real-life laboratory for the students and the residents of Oglethorpe County can still read about local events.

“It’s the conscience and soul for the county; it just can’t go away,” said NeSmith, who now sells ads to keep the paper afloat. “I won’t live in a town without a newspaper.”

About the Author