Young inmate’s stabbing death points to state prison system failures

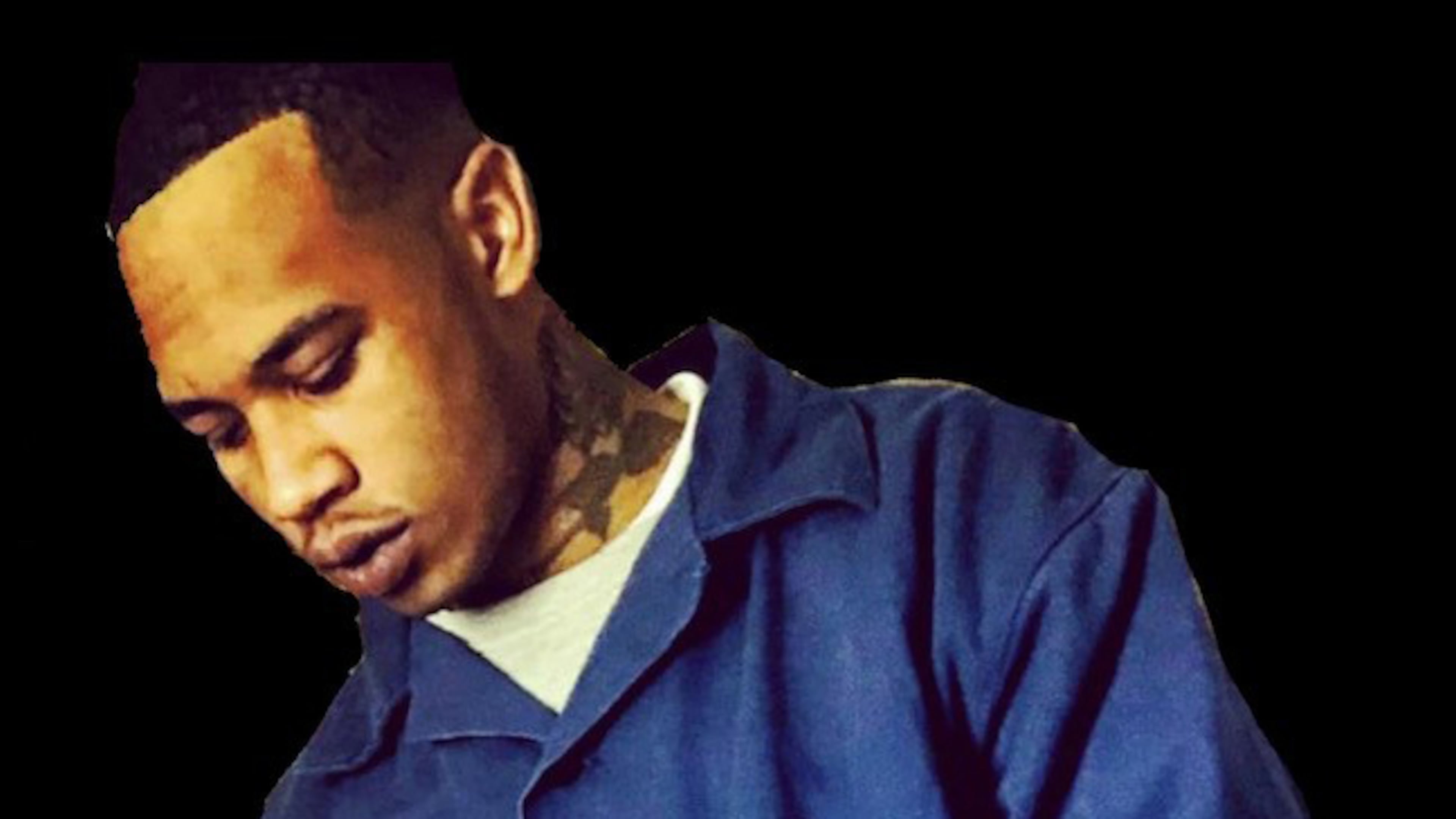

Jamari McClinton’s family had a plan in place for when he was released from prison, possibly by year’s end. He would move to Durham, N.C., to be with his half-brother, the manager of a Dollar General, and hopefully avoid the influences that had kept him locked up for a third of his 21 years.

“He wanted a change, and he was ready for it,” his mother, Doris Jones, said recently. “It’s just that one day. That one day took everything from him.”

One morning in August. One monumental slip-up by the Georgia Department of Corrections. And suddenly a life was gone, extinguished by the violence that plagues Georgia prisons.

At a time when the Georgia Department of Corrections is under scrutiny from the U.S. Department of Justice, the circumstances surrounding McClinton’s death provide yet another stark portrait of inadequate staffing, policies and oversight.

Interviews and documents reviewed by The Atlanta Journal-Constitution suggest that prison officials knew McClinton was subject to gang retaliation yet left him exposed to it anyway.

McClinton was stabbed to death five days after being transferred from Phillips State Prison in Buford to Baldwin State Prison near Milledgeville. At Phillips, he had been in protective custody following a violent confrontation with a high-ranking member of the Bloods, the largest gang in the prison system. But that was removed when he was transferred to Baldwin.

No longer protected, McClinton was stabbed in the heart as he returned to his dorm from breakfast.

An inmate affiliated with the Bloods, Brandon Pierre Hill, has been charged with the killing, and the AJC has learned that McClinton was assigned to Hill’s cell at Baldwin even though Hill’s gang membership was identified in his departmental file.

McClinton’s father, Ricardo McClinton, told the AJC that putting his son in harm’s way makes prison officials “co-conspirators.” Asked how his son could have been targeted for retaliation after being moved to another prison roughly 100 miles away, McClinton held his cell phone to his ear, as if to make a phone call.

“Gangs run the place,” he said. “They are assigning rooms, beds, everything.”

Lori Benoit, public relations manager for the Department of Corrections, did not respond to phone and email messages seeking comment.

Prisoner-on-prisoner violence has been identified as a focus of the DOJ investigation. The inquiry, officially launched in September and ongoing, follows spiking murder and suicide rates in Georgia prisons.

Since the beginning of 2020, at least 53 Georgia inmates have been homicide victims, an AJC examination found. That’s more than double the total of 21 for 2018 and 2019.

The rise in deaths comes as the state’s prisons face critical staffing shortages because of COVID-19 and other factors.

The Department of Justice declined comment on its investigation.

During a two-month stretch last summer, four inmates at Baldwin State Prison died in separate incidents labeled homicides by the Department of Corrections.

McClinton’s murder on Aug. 11 was the third of those killings. It was followed just 10 days later by that of 26-year-old Bedarius Clark, who was found unresponsive in his cell in the prison’s segregation unit. The GDC incident report described the death as “inmate to inmate assault, death, homicide.”

Clark’s killing raises additional questions because he was transferred to segregation the day after McClinton’s stabbing. The circumstances suggest that Clark, too, required protection and didn’t get it. No charges have been filed, nor has a cause of death been determined, according to the Baldwin County coroner’s office.

Gangs take hold

Prison gangs — known in the terminology of correctional institutions as Security Threat Groups — have an undeniable presence.

According to the Georgia Department of Corrections, the agency’s STG unit has identified 14,015 gang members. That’s roughly 27% of the prison population. Of the total, 4,648 have been identified as Bloods.

Every inmate profile in the department’s internal files states whether the inmate is affiliated with a gang and identifies it.

The numbers in Georgia suggest that gangs have solid footing in the prison system, said George Knox, director of the National Gang Crime Research Center.

“Since the `60s, we’ve known the power these gangs have to become the de facto operators of a facility,” he said. “It’s all about density. Think it over. Pretty much anything above 10 percent.”

A large number of prison gangs doesn’t necessarily breed violence, said Mark Fleisher, a professor at Case Western Reserve University who has researched prison management and violence. Still, he said, gang affiliations and the violence that can arise from them deserve careful consideration when shifting inmates from one facility to another.

McClinton’s transfer, Fleisher said, indicates to him that the Georgia Department of Corrections has “a terrible internal management system.”

`A cold world’

For McClinton, prison life began at 14. Ricardo McClinton said his son was in the ninth grade at Lovejoy High School in Clayton County when he was convicted as a juvenile of accessory to armed robbery. According to the father, the incident stemmed from a house party in Jonesboro where another teen used a gun to take cell phones.

While serving his sentence at the juvenile detention facility in Baldwin County, McClinton was charged with assaulting two correctional officers in separate incidents in 2016 and 2017. He pleaded guilty and received a sentence that sent him to the adult prison system for a maximum of six years.

According to family members, McClinton’s survival in prison was based in large measure on his affiliation with the Bloods and payoffs to other gang members for food, personal products and cell phone use. Members of his family would pay what he owed by transferring funds to the inmates’ Cash App accounts.

Jones said the Cash App payments were among many eye-opening aspects of prison life that emerged as she kept tabs on her son.

“It’s a cold world in there,” she said. “They’ve got phones. They’ve got TV. They’ve got drugs. They get high. They’re drinking. And they eat McDonald’s. You can’t tell me they get McDonald’s because they leave to get it. Somebody’s bringing it in.”

The cost of using prison cell phones was particularly steep, Jones said, at one point requiring her to pay an inmate $600 to cover her son’s debt.

“It’s like the phones are just in a rotation,” she said. “It’s like, if you let me use your phone, then, the next thing I know, I owe you and owe you. It’s just one thing after another. They get you.”

No more protection

McClinton’s life inside took a troubling turn when he had a falling out with the leader of the Bloods at Phillips, according to Ricardo McClinton. The elder McClinton identified that inmate as Michael Johnson, 31, presently serving 15 years for a variety of offenses in Clayton County, including armed robbery, aggravated assault and causing a riot in the county jail.

Ricardo McClinton said Johnson accused his son of stealing eight cell phones. The charge, which the father says was bogus, made his son an outcast who no longer had gang protection.

Angry over the cell phone accusation and other matters, McClinton lashed out at Johnson, stabbing him in the back with a sharpened piece of metal, on April 19. The confrontation put Johnson in the hospital overnight.

“Gangs run the place. They are assigning rooms, beds, everything."

Three days later, McClinton was placed in protective custody. Security around him was tight. Ricardo McClinton said he and Jones visited at the end of the month and found prison officials so concerned about the situation that they worried the couple had parked their cars where gang members could see them.

However, that level of protection was no longer in place when McClinton was transferred to Baldwin on Aug. 6. There, he was placed in “H” dorm, a large building where inmates can move about freely. At 7:35 on the morning of Aug. 11, he was leaving the dining hall when he was stabbed on the sidewalk. Within 20 minutes, he was pronounced dead.

Hill has been charged with stabbing McClinton to death with a “homemade weapon.” The 27-year-old from Augusta had only recently started a third stint in the prison system for robbery and similar offenses and was eligible for release in October, according to GDC records.

McClinton’s family members said he never mentioned Hill in his phone calls from Baldwin, but he did say he was worried about his safety. On the day before he was killed — a Tuesday — he showed particular concern for what might happen the next day, his mother said.

“He was worried about Wednesday,” Jones said. “It was `Wednesday this, Wednesday that, Mama. I just gotta get through Wednesday.’ I didn’t quite understand what Wednesday was, but he was definitely worried about something.”

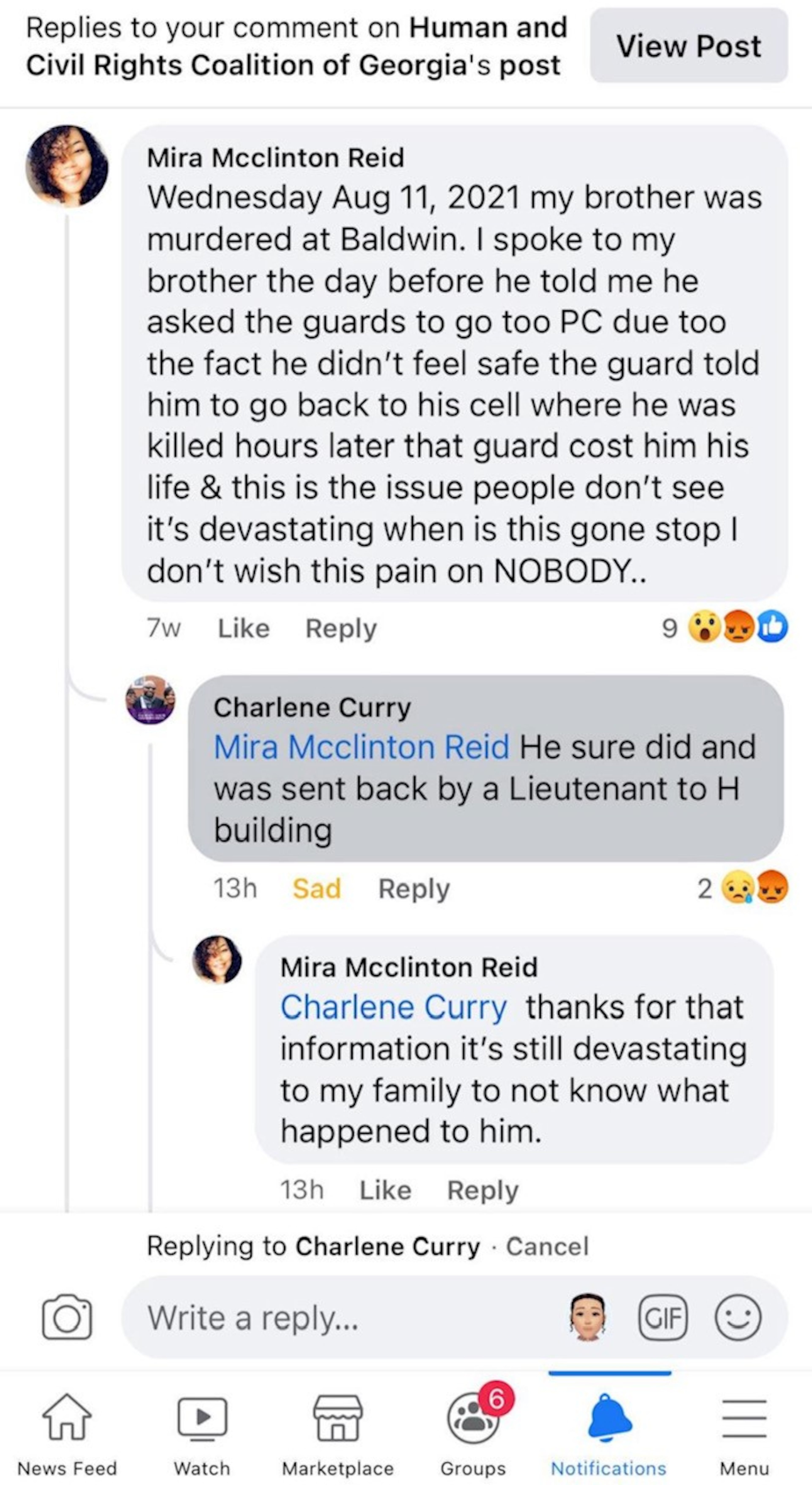

Posting on Facebook after McClinton’s death, his sister, Mira McClinton Reid, wrote that her brother told her the day before he died that he had asked a guard to place him in protective custody and was told to return to the dorm instead.

Responding to Reid’s post, a guard at the prison, Charlene Curry, wrote: “He sure did and was sent back by a Lieutenant to H building.”

Curry didn’t respond to a request to be interviewed for this story.

Reid said the Facebook post is just one of several things that lead her to believe the Department of Corrections is “one thousand percent” responsible for her brother’s killing.

McClinton’s family members now talk, often tearfully, about how he will never get to experience the life they planned for him in North Carolina. At the same time, they struggle with questions. How did this happen? Why didn’t anyone in the prison system see this coming?

“They don’t have the people,” Jones said. “And then the people they do have ... Well, you have to be able to react, you gotta have heart. If you don’t have heart and you really don’t care, you’re underpaid, you’re scared yourself, what do you do?”

More Stories

The Latest