‘We are here’: Latino communities grow in rural Georgia

On a warm Saturday in December, a Christmas parade snaked through Tifton, a town of 17,000 located amid sprawling South Georgia farmlands. The parade is a tradition dating back decades, but there was something new to the 2021 edition, which marked the event’s return after a pandemic break in 2020. For the first time, the parade featured a float from the Latino Community Fund (LCF Georgia), an Atlanta-based nonprofit.

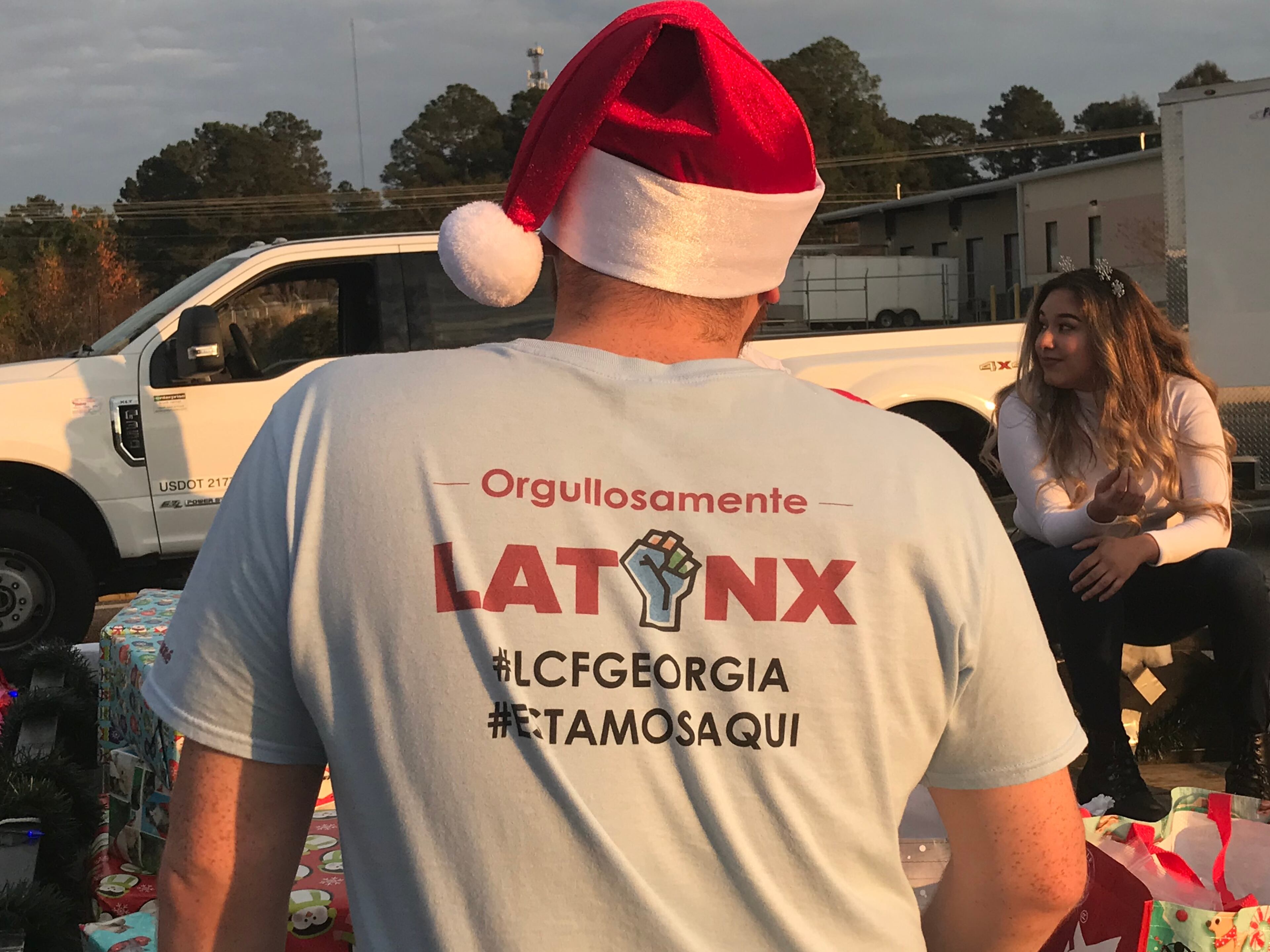

As it wound its way through the parade route, the LCF Georgia float played well-known Latin American villancicos, or Christmas carols, a departure from the English-language classics other floats stuck to. Along with Santa hats, LCF Georgia staffers wore shirts that said “proudly Latinx” and “estamos aquí,” or “we are here.”

Many of the Hispanic families in attendance that day took notice. “Miren, son latinos!” a young boy in the crowd told his parents. “Look, they’re Latino!”

The sights and sounds of the Tifton Christmas parade reflect rural Georgia’s changing demographics. In Tift County, where the town of Tifton is located, the total population grew by just 3% from 2010 to 2020, according to data from the 2020 U.S. Census. During that time period, the Latino population countywide surged by nearly 30%, an increase of over 1,000 people.

Even as the state tallied a 10% overall population jump over the decade, rural communities shrank. Rural areas are defined by the U.S. Census Bureau as being low-density and removed from urban centers. Among Georgia’s 159 counties, 54 were deemed rural in the 2020 count. Across all rural counties, the population decreased by over 100,000 residents, according to an AJC data analysis, a drop-off driven by reductions in the white, Black and Asian populations.

But as the non-Hispanic population went down, the Hispanic population grew.

Raw numbers are small — there were 45,802 Hispanic residents in the 54 rural counties in 2020, a net official increase of just 1,500 people compared to 2010. Still, a growing Latino population in the Georgia countryside suggests increased diversity in the state isn’t limited to urban areas.

Latinos diversifying rural Georgia

It’s a national trend: According to a study of rural diversity by the Brookings Institute, a nonprofit public policy organization, burgeoning Latino populations are diversifying rural regions across the country, providing a “demographic lifeline” bolstering otherwise shrinking communities.

Awareness of changing rural Georgia demographics — and new community needs tied to the COVID-19 pandemic — fueled LCF Georgia’s expansion to the Tifton area starting in 2020. With a team of eight local “community navigators,” all sons or daughters of first-generation farmworkers from Latin America, the nonprofit has been granting financial assistance to local families who lost income during the pandemic. They’ve also helped coordinate vaccination clinics and know-your-rights initiatives to prevent worker abuse on the fields.

“In the metro Atlanta bubble, people aren’t fully aware of the magnitude of the Latino population that exists” in rural Georgia, said Pedro Viloria, South Georgia manager at LCF Georgia.

Like other local Latino advocates, Viloria said he suspects the census failed to capture the true size of the Hispanic population in the state, given noncitizens’ longstanding concerns around taking part in the count. Those concerns were amplified in 2020 when the Trump administration unsuccessfully attempted to add a question to the census questionnaire about citizenship status.

Hesitancy could have been especially pronounced in rural communities, where many unauthorized farmworkers work and live. According to a 2018 report commissioned by the U.S. Department of Labor, 49% of the U.S. agricultural workforce is undocumented.

“I think there definitely was an undercount,” Viloria said. “We know that the [Hispanic] community is bigger than what’s reported.”

Search for opportunities

Community advocates say Latino migrants are drawn to the opportunities for economic advancement in rural regions, where newcomers have been able to find lower costs of living and plentiful jobs.

“As urban areas gentrify and the costs go up, that pushes out some Latinos,” Viloria said. “Even Buford Highway, which has historically welcomed many Latino immigrants, is seeing some gentrification.”

In 2019, Arthur Morin helped create the Valdosta Latino Association, a nonprofit that serves and promotes the integration of Latino residents in the Valdosta area. Many small counties outside Valdosta registered significant jumps in their Hispanic population since 2010, including Lanier County which showed a rise of 24% in residents who identified as Hispanic.

According to Morin, Hispanic workers with or without legal status tend to look at agricultural worksites for their first jobs when they settle in rural Georgia. As time passes, those workers may branch out and pursue opportunities in industries such as construction or hospitality.

“Something I think is very interesting … is the diversity and the fact that the Latino population is widely distributed,” Morin said. “They’re in the cities, they’re in the countryside … Georgia has Latinos everywhere.”

Ulyssa Muñoz is a South Georgia native, and a community navigator with LCF Georgia. She says a big draw rural areas have is a perception among migrants that they will be safer from immigration authorities there. That perception is well-founded: two metro Atlanta counties — Gwinnett and Cobb — were among those that led the country in terms of immigration enforcement through 2020, before local law enforcement pulled out of a program with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE).

Surge of seasonal farmworkers

A notable source of Hispanic migration to rural Georgia in the past 10 years has been the explosive growth of the H-2A visa program for seasonal farmworkers. According to the federal Office of Foreign Labor Certification, Georgia had 27,614 H-2A positions certified in fiscal year 2020, up from roughly 5,500 in fiscal year 2010, with the overwhelmingly majority of workers coming from Latin America.

If they were present in the state on census day – April 1, 2020, a date that coincided with the busy spring harvesting season – temporary farmworkers were eligible to be counted, but there’s no way to know if they were.

Though H-2A workers remain in the state only for months at a time, they can become fixtures in the places they live and work.

“A lot of our farms will see a large portion, north of 80 to maybe even 90% of those workers return year after year to the same farm and become part of that community,” said Chris Butts, executive vice president of the Georgia Fruit and Vegetable Growers Associations.

The man behind the wheel at the LCF Georgia Christmas float is part of the Latino population that has settled in rural Georgia over the past 10 years.

Victor Muñoz, 27, made the first of six trips to Tift County in 2015, as an H-2A seasonal farmworker. Each year he came, he stayed in Georgia for 10 months, harvesting everything from collard greens and kale to onions and cilantro. After marrying LCF Georgia’s Ulyssa Muñoz in 2021, Victor Muñoz is here permanently, and still working in the fields. It’s a lifestyle that suits him, he says.

“I like this area, it fits me … I grew up in the countryside.”

On the farm, Muñoz works alongside his two brothers, both of whom are H-2A workers, or “contratados.”

“Most of [my coworkers] are Mexican,” he said. “The work on the field is hard but Mexicans find a way to fight through it, because we come from far away and we have to get ahead.”

Lautaro Grinspan is a Report for America corps member covering metro Atlanta’s immigrant communities.