Virus a sudden setback for school laboring to lift children’s lives

For Atlanta’s most vulnerable students, school is a refuge — a place for learning as well as food and family services.

The coronavirus shutdown has threatened those safe havens, and the blow is especially hard for schools like Harper-Archer Elementary, one of about two dozen Atlanta turnaround schools trying to help students who already lag academically.

Losing more than two months of in-person instruction at Harper-Archer, which serves students from some of Georgia’s poorest neighborhoods, likely will widen that gap despite educators’ best efforts.

VIDEO: About Harper-Archer Elementary

The virus closed the Westside school building and others throughout metro Atlanta three weeks ago. Wednesday, the governor ordered students to stay home for the rest of the school year.

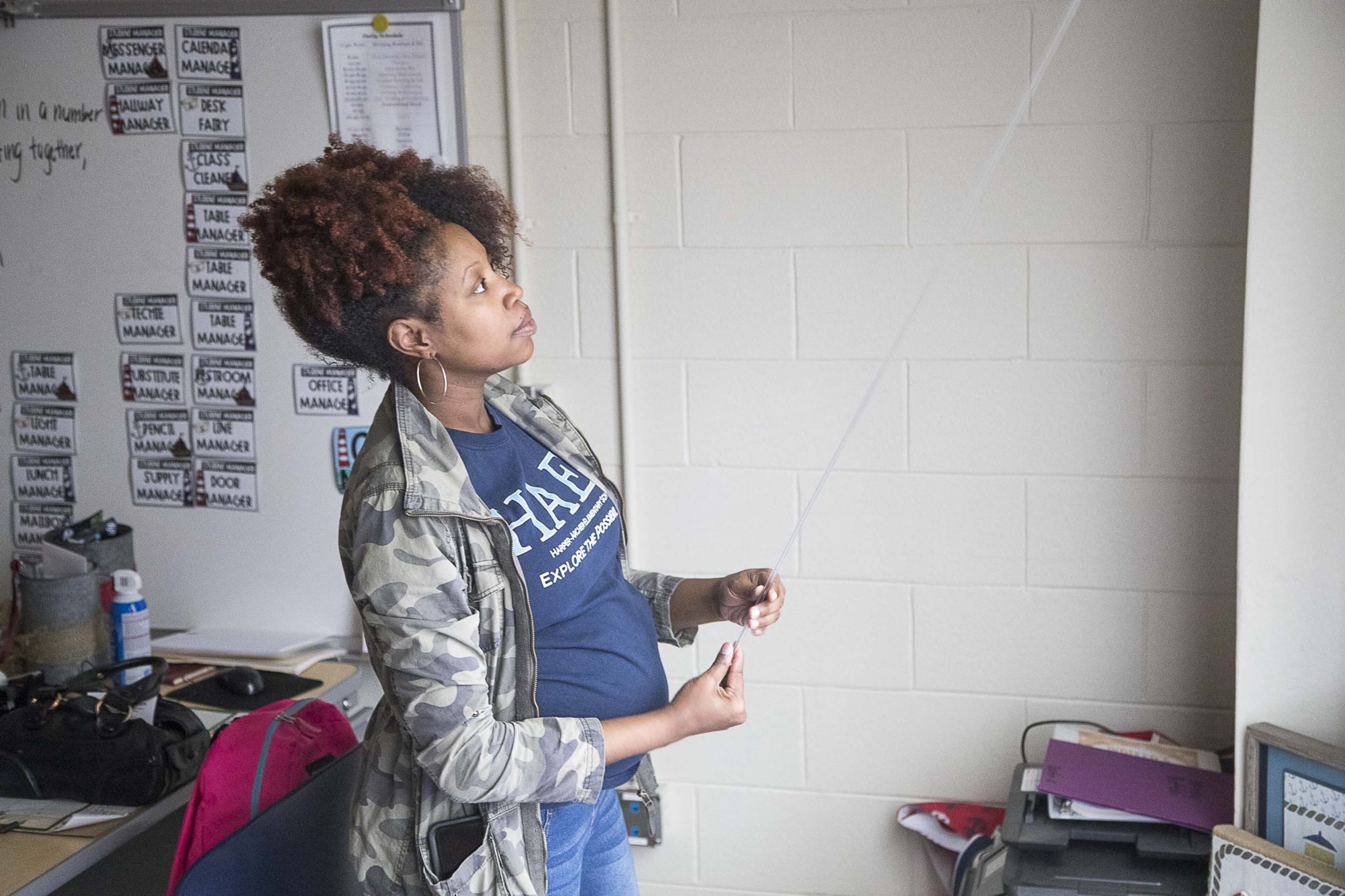

Harper-Archer Principal Dione Simon Taylor never imagined such a setback when the school opened in August. She’d been chosen to lead the new school created by the merger of two academically troubled elementaries, and her goal has been to prove that her students can be high achievers.

INSIDE HARPER-ARCHER: MORE STORIES

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution was granted access at the start of the school year to observe the turnaround effort, and spent months documenting Harper-Archer’s work so far.

Even before the closure, the school faced an enormous, years-long challenge to boost learning for students who don’t have the same foundational knowledge as those from more affluent families. Now, the obstacles are bigger and academic gains will be delayed.

“It will widen the gap, which means that our efforts have to be more aggressive than we had been before,” said Taylor. “There’s just so much more, other than academics, that plays into this for our kids … People are going to have stories that are beyond what we can imagine because life is real.”

Sudden, hectic last day

As soon as Taylor found out the district was closing buildings, she and her team went into high gear.

She gathered the assistant principals, instructional coaches and others for a meeting just after 8 a.m. on that last day to discuss everything they needed to accomplish in the next seven hours. It was a long to-do list.

Staffers printed so many copies of worksheets that a copier ran out of toner. A library aide stocked a cart and rolled it down the hallways so students could check out books to borrow. One teacher stopped at a used bookstore to buy nearly 80 books for her second graders to take home.

They put lesson plans online and taught children how to log into computers. They needed to make sure the school’s many needy families knew about food distribution sites and internet providers offering free or discounted access.

INSIDE HARPER-ARCHER: THE PHOTOS & VIDEOS

» ‘You can always dance it out’

Students in Alecia Westbrooks’ fifth grade class were sent home with a packet full of worksheets, sharpened pencils, her phone number and paperback copies of Roald Dahl’s “The BFG.” As they stuffed their backpacks, one girl exclaimed that she’d never had so much homework in her life.

Westbrooks told them to check in on each other while they were gone, to stay in contact with her and to be safe.

“Don’t be out there running these streets, running back and forth to the Dollar Tree every five minutes,” she said, as her students prepared to leave. “Don’t get loose. Listen, do not get loose.”

When the last bus pulled away, several staffers lined up on the sidewalk to wave goodbye to students.

“Wash your hands,” they shouted.

Teachers unplugged small appliances and closed the window blinds. Taylor urged them to take personal items of value home with them. Break-ins hadn’t been a problem, but now the school would be vacant for who knows how long.

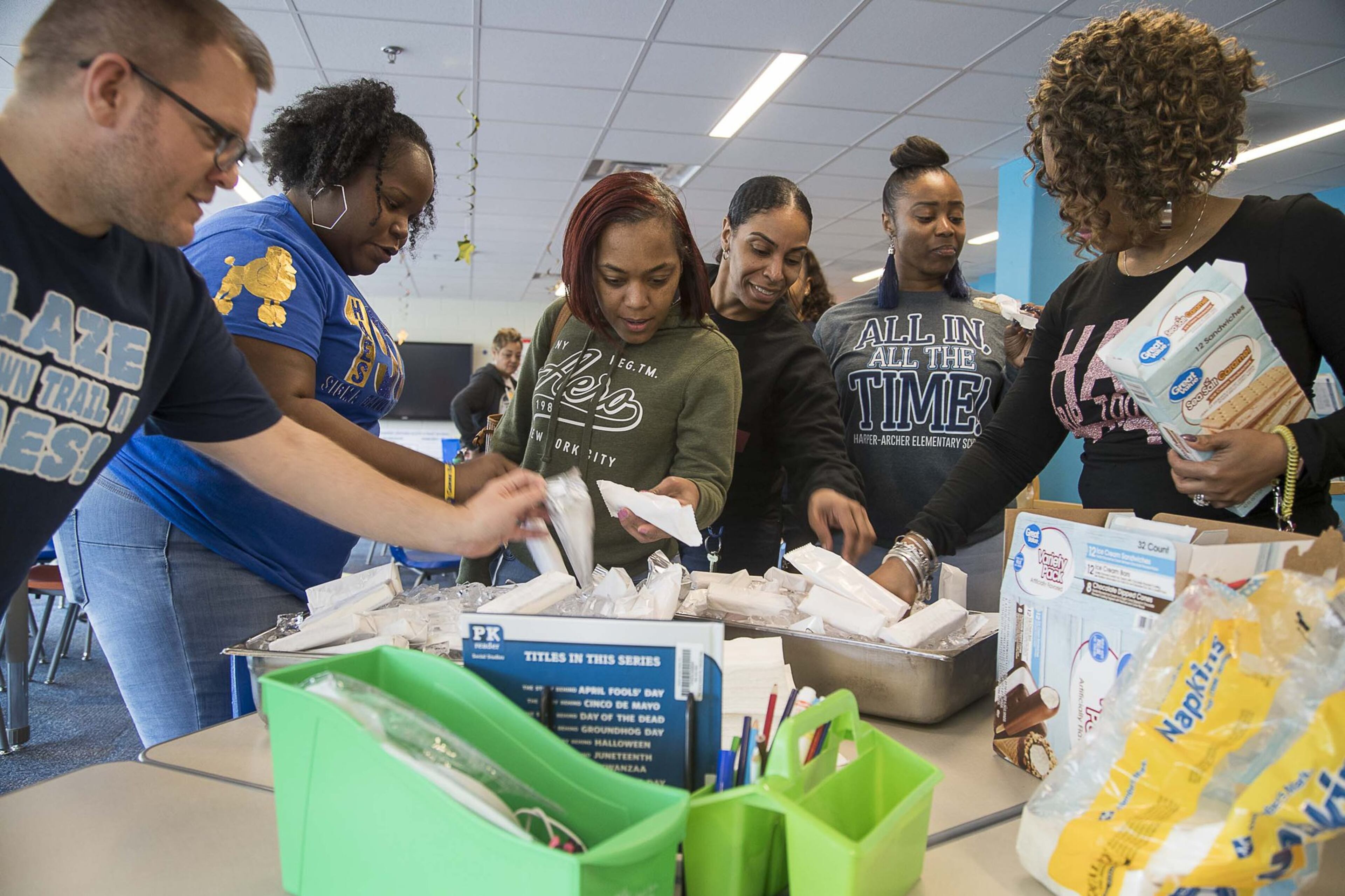

Before the building emptied, Taylor held an all-staff meeting. She passed out ice cream sandwiches and reminded teachers to clock in daily from home and keep their cellphones on.

“We are not off work; we are just not at work,” she said.

Plans, benchmarks upended

Atlanta’s districtwide turnaround strategy, launched in 2016, targets about two dozen struggling schools and provides extra services and academic support at Harper-Archer. The challenge is daunting. Critics have urged the district to hold schools more accountable and intervene more quickly when they don’t get better, and experts caution that boosting chronically failing schools can take several years.

Stability is critical in turnaround schools, and the coronavirus crisis has upended schoolhouses and homes. The need to close buildings and switch to distance learning will disproportionately harm low-income students who are already behind, experts predict.

“Just the fact that their day-to-day lives are so disrupted, I think it really doesn’t bode well for students who are most in danger of not doing well in school,” said Lam Pham, whose research at Vanderbilt University has focused on school turnaround efforts. “You can’t expect students to grit their way through a pandemic.”

Parents who live paycheck-to-paycheck may not be able to stay home to oversee their children’s schoolwork, or they’re among the millions of workers across the United States who are suddenly unemployed and scrambling to meet basic needs. And what happens if they get sick?

In some schools, students just don’t have the same foundation for learning as others. It’s a problem Atlanta’s school district has been confronting for generations, and the district has been in a multiyear, multimillion-dollar project aimed at helping.

Some steps, such as turning six schools over to charter groups to run, have been controversial and watched nationally, since educational inequity is a problem all over the country, not just in metro Atlanta.

Teachers know that whatever they do in the classroom, they can’t control some factors – parental involvement and generational poverty, for example – that have powerful influence on their students’ ability to learn. Atlanta’s results so far underscore just how difficult turnaround is. Schools have seen some gains, but there’s minimal evidence it’s because of the turnaround investments.

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution wanted to know: Just how does the school give students the proper education they’ll ultimately need to compete with their peers for adequate jobs, and to be responsible, productive citizens in our communities?

To answer that question, we knew we had to be in the classrooms and hallways of a school trying to find solutions to these challenges.

We knew we had to speak to community residents and parents.

The AJC asked Atlanta school officials to give us unprecedented access to a school being targeted for special attention because of its long-standing challenges.

Harper-Archer Elementary, the “turnaround school” the district selected when the AJC proposed this project, is new. The west Atlanta school opened this year to serve neighborhoods that are among the poorest in Georgia.

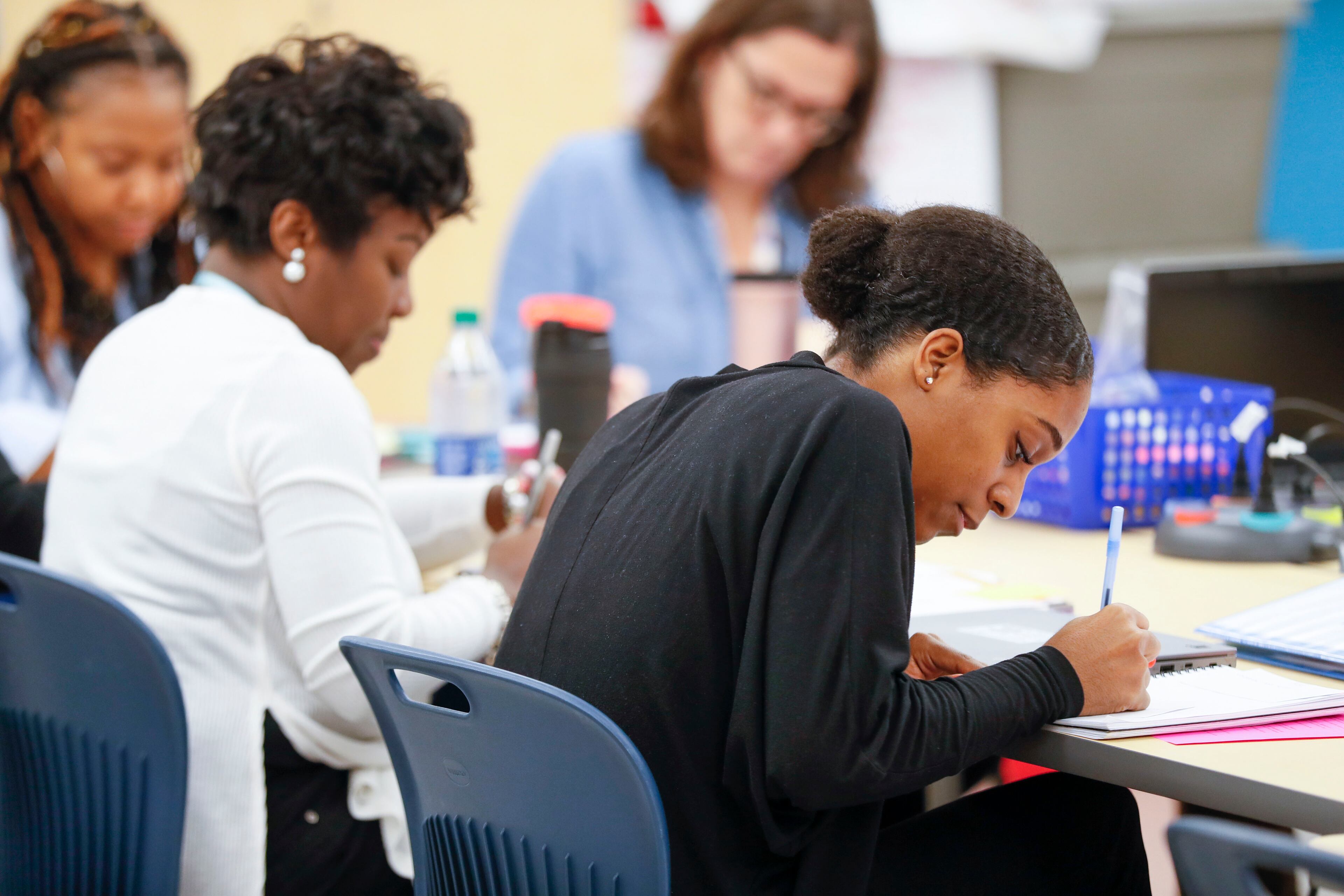

School officials allowed our reporter and photographers a close-up view of the people and the everyday goings-on in the life of that school community.

Over several months, AJC reporter Vanessa McCray and photographers Alyssa Pointer and Bob Andres spent many days observing, interviewing and recording the efforts and the motivations of the dozens of people who are trying to ensure that what’s in store in the lives of the children there can be brighter than their beginning.

Successful communities support and invest in the education of children. Strong schools use that support to set high expectations and to execute bold, cutting-edge initiatives.

Not every school in Atlanta can claim such success. For some city schools, the challenges seem too great to overcome.

Students at Harper-Archer Elementary School come to class each day from Atlanta neighborhoods struggling with the harmful side effects of generational poverty. They also suffer from inconsistent parental engagement and many of these children lack basic reading skills – the foundation for academic accomplishment.

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution wanted to know, just how do teachers, principals, counselors, and other school staffers try to give these children the proper education they’ll ultimately need to compete with their peers for adequate jobs, and to be responsible, productive citizens in our communities?

Atlanta Public Schools gave the AJC unprecedented access to the inner workings of its efforts to turnaround this school. The stories inside this special section are the result of our reporter and photographers spending dozens of hours at Harper-Archer over several months.

If the folks at Harper-Archer are successful with their bold plans, the school will serve as a template for other urban schools struggling to meet basic standards.

We interviewed school leaders, teachers, community residents, and parents, to get the full picture of the magnitude of the challenge and of those who are trying to find solutions.

They are stories of determination and hope.

- Todd C. Duncan, Senior Editor Local Government and Education

Measuring how schools are doing also will be tougher. The state has suspended its Milestones tests given in the spring. Harper-Archer can track students’ progress in other ways, but now it will take two years to establish the baseline marker used by the public.

New turnaround schools can use that first-year state test data to show quick wins and foster continued support for their efforts, so educators will have to rely on other indicators of improvement like enhanced parent engagement, Pham said.

They’ll also need to spend the summer months thinking about how to accelerate learning even more than before, Taylor said. Teachers began texting her about planning for next school year immediately after they learned the closure would last through May. When students return, they’ll have to devote more time to remediation and re-establish rules and routines.

Younger students learning to read likely will feel the impact of the time away the most, Taylor said. They’re also the ones teachers have had the hardest time connecting with online because they can’t do it without a parent’s help.

The school has focused on the building blocks of literacy, and for students on the cusp of reading, the closure could cause a slip in skills. Teachers are working on ways to help students along while they are at home, but it’s hard to replace an experienced instructor who understands the science of reading.

Help for parents goes on

After the Harper-Archer building closed, the school distributed more than 550 Chromebooks and iPads so children could keep up with digital lessons.

Parents pulled in the driveway and gloved staffers handed just-cleaned devices through open car windows. Some parents walked to the school in the rain or boarded buses to pick them up.

First grade teacher Jocelyn Davis met up with a handful of families to deliver devices that first weekend and worried about the few she couldn’t reach in the first week.

She tried not to compare herself to teachers in other schools who quickly began posting creative lessons online. Her first focus had to be making sure her students had food, a school iPad, internet, paper and pencils.

Westbrooks created a schedule with “brain breaks” built in. She suggested art, music and physical education videos, and introduced students to virtual field trips. She began using video conferencing to give interactive lessons.

Throughout the school year, Harper-Archer staff have used “All in, all the time” as a rallying cry. “We never knew how far we would have to be in,” Westbrooks said.

As the virus shuttered more businesses, Harper-Archer’s parent liaison began offering same-day help to parents to polish their resumes.

The Parent Teacher Association, formed just three months ago, started a weekly “Stay-in storytime” live on social media. During the first one, Taylor Robinson, the group’s president, recorded herself and one of her daughters reading a book together. A handful of classmates and parents tuned in and greeted each other in the comment section.

Robinson, who is able to stay home with her children, has called and texted teachers and found they’ve been “ahead of the game.”

On a recent morning, she supervised as her daughter completed a writing assignment using the “OREO” method. Students start by stating an opinion (O), give reasons (R) and examples (E), and then restate their opinion (O). Robinson said her daughter writes the passage, shows it to her, they take a photo and then turn it in.

‘We’ve got you’

Some parents have attempted to meet the new demands but encountered difficulties, like the mom who tried to set up internet service but had to wait for her apartment managers to approve installation.

Students will not receive a “zero” grade for failing to turn in assignments and will be given multiple opportunities to complete the work, Superintendent Meria Carstarphen has said. She urged patience as principals figure out how to handle those situations.

In a YouTube video posted this week, principal Taylor pleaded with parents to contact teachers often. Without parents helping and urging children to do their schoolwork, learning could stop completely.

“You can give them a device and upload a million assignments, but it still requires a parent,” she said earlier.

For some parents and teachers, the frequent communication may build deeper relationships.

Clovis Lyons, a mom of three Harper-Archer students, said her refrigerator broke just before school buildings closed. She lost about $700 worth of food. Family and friends offered support, and she signed up for food stamps. A teacher also brought over supplies.

“That was a blessing. You don’t see stuff like that. A long time ago, it used to be like that with teachers who actually cared,” said Lyons, who is currently out of a job because the preschool where she works is closed.

Lyons is using the time off to take online college courses, and now she and her children can do their homework together.

The difficulties of the last few weeks underscored what Taylor said she’s known all along: Love conquers all. A flash of that optimism swept over her face as she greeted parents with air kisses when they came to pick up computers on a recent damp afternoon.

“We’ve got you,” she shouted from afar, through open windows and across car hoods.

She remained upbeat after the governor announced that classrooms wouldn’t reopen. Her first thought? How to celebrate students and staffers when they can’t all be in the same room for an end-of-year awards day.

“There are so many beautiful things that happened this year,” she said.

Even if they have to redo the first year, even if it takes longer to turn around Harper-Archer, she’s not giving up.

“We are not going to let this take us out,” Taylor said.

» NEXT STORY: Developing a plan for failing schools

Inside a turnaround school: APS’ formidable challenge

In dozens of Atlanta schools, students have fallen behind. They struggle with reading, writing and math, and many depend on schools to provide social services, help for their families and a little extra love. In 2016, Atlanta Public Schools launched a turnaround effort aimed at improving its chronically failing schools. Harper-Archer Elementary opened in August to serve students from some of Georgia’s poorest neighborhoods. Over more than six months, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution has gotten a close-up look at Harper-Archer’s work, documenting the hardships and triumphs.