Treating Jimmy Carter's cancer

Melanoma, the cancer that has afflicted Jimmy Carter, is a quick and insidious killer. It typically is a cancer of the skin that readily spreads to other parts of the body. In years past, a diagnosis was often a death sentence, but recent advances in treatment have changed the calculus for many melanoma patients.

Carter announced last week that his melanoma had spread to his liver and brain.

Cancer patients are said to be in one of four primary “stages” of cancer. Carter’s melanoma is stage IV, the most advanced and difficult to treat.

Stages and survival rates of melanoma

The four primary stages are subdivided according to the progress of the disease within that stage. Important note: the five-year survival rates below were set in 2008; cancer research has made great progress in melanoma treatments since – outcomes that are not reflected in the rates:

Stage I: a small tumor has formed in or on the skin but has not yet spread.

Five-year survival rates

- Stage IA: 97 percent

- Stage 1B: 92 percent

Stage II: the tumor is larger and may have ulcerated the skin.

Five-year survival rates

- Stage IIA: 81 percent

- Stage IIB: 70 percent

Stage III: cancer spreads in the skin and to one or more lymph nodes.

Five-year survival rate:

- Stage IIIA: 78 percent

- Stage IIIB: 59 percent

- Stage IIIC: 40 percent

Stage IV: The cancer has metastasized (spread) to other organs including, in 40 percent of cases, the brain.

Five-year survival rate:

- Stage IV: 10 to 15 percent

New treatments

Melanoma treatment entered a new era in 2011 with the development of the first “immunotherapy” cancer drug, which rallies the patient’s own immune system to fight the disease. The government has approved six such drugs, and they’ve been shown to shrink tumors in 90 percent of patients. The drug being used to treat Carter costs about $100,000 for a course of treatment.

Aging and cancer

Doctors sometimes call cancer a “disease of aging”: 77 percent of all new diagnoses are among people 55 and older. With roughly 70 million baby boomers, cancer diagnoses are expected to increase substantially. The overall cancer death rate fell more than 22 percent from 1990-2011. Today, there are more than 14 million cancer survivors in the United States.

The medical team

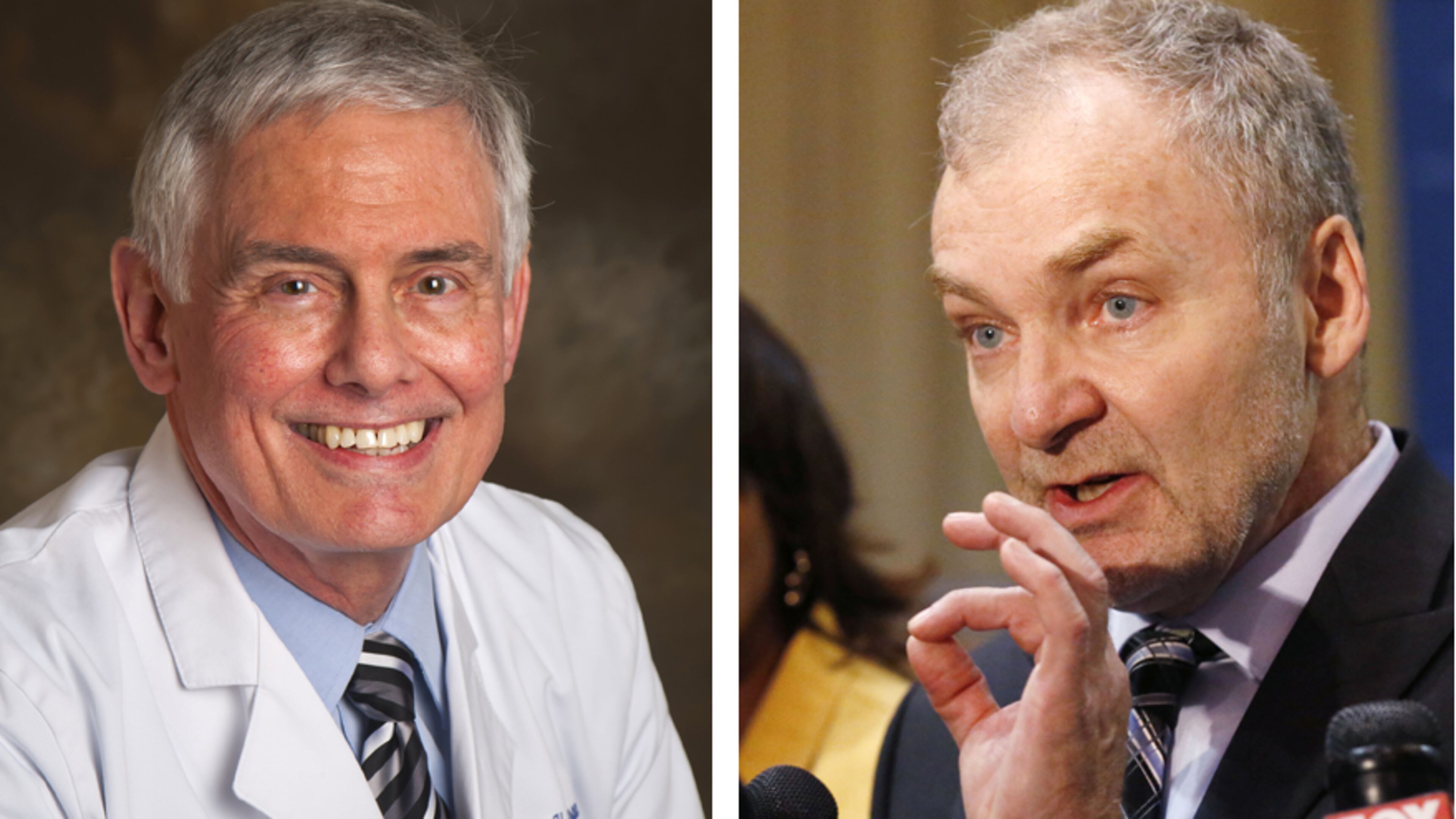

The two doctors taking care of Carter are Dr. Walter J. Curran Jr., executive director of Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University and one of the nation’s leading radiation oncologists, and Dr. David Lawson, a medical oncologist and head of the melanoma program at Winship.

Dr. Walter J. Curran Jr. 64

Curran knew from the time he was a kid growing up in Beverly, Mass. that he wanted to be a doctor. But he also knew he wanted to be a teacher.

When he enrolled at Dartmouth College as a freshman, he told his adviser that he wanted to do both.

“That sounds like a stupid idea,” his adviser replied, Curran recalled on Friday.

Curran ended up teaching middle school science before he decided to enter the Medical College of Georgia, now called Georgia Regents University. Once in medical school there, he said, Curran found that “every aspect of every course” led him to oncology.

He specializes in the treatment of brain tumors and locally advanced lung cancer. He also is a director of the American Society of Clinical Oncology and the group chairman of NRG Oncology, the largest of the five clinical trials network groups funded by the National Cancer Institute.

He has been chairman or co-chairman of more than 40 clinical trials, and he has authored or co-authored more than 700 scholarly papers and abstracts.

Curran was a track coach during his middle-school teaching days and remains an avid runner. Soon after taking over at Winship, Curran decided the institute needed a yearly 5K run. In 2011, the Winship Win the Fight 5K was launched, with Curran its biggest cheerleader — and fastest runner in his age group. The fifth run will be Oct. 3. Money raised from that event goes to research at the institute.

Curran said he believes breakthroughs in treatment are close in many cancers. And while he is happy that survival rates are better than ever — with two out of three cancer patients surviving, Curran said, “We’re looking for that third person.”

Dr. David Lawson, 70

Like Carter, Lawson grew up in a small Georgia town, Perry, about 60 miles from Plains. And, like Carter, his Southern roots are evident in the rich cadences of his speech.

Lawson went to undergraduate school at Duke University and then went to Emory for medical school in 1970. He never left.

He has been involved in several clinical trials over the years involving immunotherapy and authored many journal articles. Like many melanoma experts, Lawson is thrilled about the advances that have come from immunotherapy in recent years.

Immunotherapy, he said, works by “taking the brakes” off the immune system so that it can fight the cancer cells.

At first, a foreign substance triggers a response from the immune system, but that response must be shut off. So the body pulls back, shutting down the immune system.

“The idea is, when you have an immune response, the body tends to want to suppress it,” explained Lawson.

Researchers like Lawson and others have found that “taking the brakes” off the system can benefit patients with melanoma.

Equally exciting, Lawson said, have been breakthroughs from the immunotherapy drugs that allow them to work on tumors that have spread to the brain.

“Brain metastases have been the curse of cancer therapies,” Lawson said. That is changing, he explained, because, with its natural immune system activated, the body can fight some tumors in the brain. That is a major breakthrough for people, like Carter, who have brain metastases.

“We have two trials here now looking at melanoma brain metastases,” Lawson said.