The King Generation is nearly gone; who is stepping up?

Sitting in an Ebenezer Baptist Church pew ten days ago at John Lewis’ funeral, Jared Sawyer Jr.’s mind raced back to 2016.

Then 18 years old, he visited Lewis in Washington, D.C., for the opening of the National Museum of African American History and Culture. After an hour of chatting in Lewis’ office, Sawyer excused himself to go to the White House, where at the invitation of President Barack Obama he would give a speech on the museum’s significance.

Lewis, who was headed to the White House for the same ceremony, asked, “Would you like to go with me?”

They walked along the National Mall, with the Lincoln Memorial, where a 23-year-old Lewis had spoken so brilliantly at the March on Washington in 1963, serving as a backdrop. Lewis was the last remaining speaker from that historic day, which included the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and other giants of the movement who have passed on. Sawyer recalls people constantly stopped Lewis on their walk, wanting to talk. He asked the congressman and civil rights icon if he ever got tired of it.

Lewis told him: “Why would I? It is an honor to talk to them. And it is affirming that they have not forgotten, so that history will not repeat itself.”

Sawyer has become one of the links between that history and the new, loosely organized movement under the banner of Black Lives Matter, which is roiling the national consciousness with protests across the nation. The new generation of young protesters look to those like Lewis, but they face their own set of challenges and issues.

Lewis tied the two movements together in six words in his last essay, released the day of his funeral.

“Emmett Till was my George Floyd,” he wrote.

Till was a 14-year-old Black boy in Mississippi who was beaten, murdered and thrown into the Tallahatchie River in 1955 for supposedly saying something inappropriate to a white woman. His death galvanized the civil rights movement and got international attention.

The death of George Floyd this year was one of a string of killings of Black people that kindled protests across the U.S., demanding social justice and an end to police and vigilante violence.

Weeks before he died, Lewis, in his last public appearance, visited Black Lives Matter Plaza in front of the White House, as an act of solidarity with the nascent movement.

Then he passed the baton with these words in his essay, “Ordinary people with extraordinary vision can redeem the soul of America by getting in what I call good trouble, necessary trouble.”

“In my life I have done all I can to demonstrate that the way of peace, the way of love and nonviolence is the more excellent way,” Lewis wrote. “Now it is your turn to let freedom ring.”

The Foundation

The nation lost in the last three months three pillars of the American civil rights movement, each of whom had close professional and personal ties to Martin Luther King Jr.

On July 17, Lewis, 80, and C.T. Vivian, 95, died peacefully in their homes in the city’s black enclave, Southwest Atlanta. Three months earlier in the same neighborhood, Joseph Lowery died in his home at 98.

King’s generation were often called “foot soldiers” in the movement. Like the veterans of World War II, a dwindling number remain to remind America of what the country has been through, what was gained through their efforts and how much work still needs to be done.

King died at 39 years old in 1968. Ralph David Abernathy, Hosea Williams, Fred Shuttlesworth, Wyatt T. Walker and James Orange and many others died as old men. Rosa Parks, Coretta Scott King, Dorothy Height and Ella Baker also lived full lives.

Collectively, they helped transform America by exposing the country’s glaring contradictions, and they got laws and legislation passed to even the playing field — at least on paper.

“Their impact was so enormous that I search for words to describe it,” said Johnnetta Betsch Cole, the president of the civil rights group the National Council of Negro Women. “But if we give an assessment today, we can say that 10 years from now, 100 years from now, whenever we finally get the work done, we will still be talking about them.”

When Lewis and Vivian died on the same day, historians were reminded of July 4, 1826, when John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, America’s second and third presidents, died within hours of each other.

Adams and Jefferson were Founding Fathers and crafted a Declaration of Independence that promised: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

But that wasn’t true. Many of them owned slaves.

Even after The 13th Amendment of 1865 officially ended slavery, Blacks endured another 100 years of Jim Crow and segregation until the passage of the Civil Rights and Voting Rights acts in 1964 and 1965 — due to the efforts of the civil rights workers.

Jesse Jackson, who ran for president in 1984 and 1988, said leaders of the Civil Rights movement should be considered a second set of American Founding Fathers.

“In 1776, a white, nationalist nation was born,” Jackson told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. “But America was born in Selma when Americans found democracy.”

It was there, after news films of violence done to peaceful protesters were broadcast, that Americans had had enough. On Feb. 16, 1965, Vivian was beaten by law-enforcement outside of the Dallas County Courthouse when he tried to register Black voters.

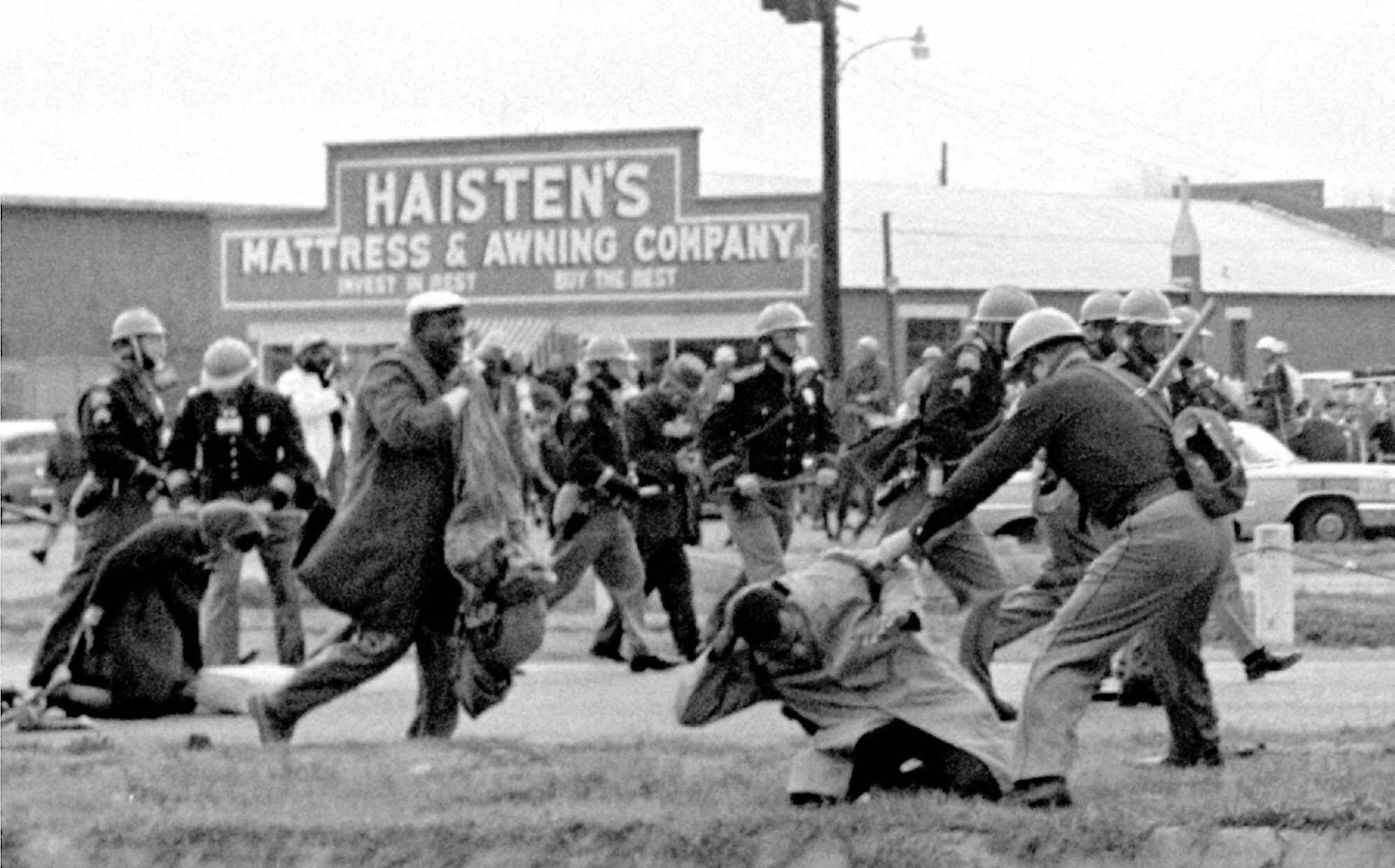

On March 7, 1965, Lewis was beaten to the brink of death by state troopers as he and Hosea Williams tried to lead marchers across the Edmund Pettus Bridge.

Within months, the Voting Rights Act was proposed and passed.

“Did we know that we were changing America?” asked Bernard Lafayette, Lewis’ former college roommate and a co-founder of both the Nashville Student Movement and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. “Yes, we did.”

Yet work remains to be done, he and others say. Changing all hearts and minds has been a tougher, longer project.

A movement matured

Derrick Johnson, 51, president of the NAACP, said the civil rights movement never ended.

“It is a continuum. It didn’t start with those individuals and will not end with them.”

It’s bigger, broader. There are actually more people working in the arena of civil rights today than there ever has been, because of the work done in the 1950s and 1960s, he said.

“Environmental, criminal justice, voting, housing policies, economic justice. You name it, you can find young, older and middle-aged people all lending their voices to advance social justice for society,” Johnson said.

But unlike the civil rights movement, where strong personalities emerged with enough power to demand audiences with presidents, a new generation of grassroots activists without centralized leadership are building networks and strategic alliances through social media hashtags. They have yet to earn their sit-downs.

Mary-Pat Hector, a 22-year-old Spelman College graduate, who has been planning and leading several of the Atlanta protests, works for the Lowery-founded Georgia Coalition for the People’s Agenda as a black youth vote coordinator, where she trains poll workers.

No one could ever fill the shoes of leaders like Vivian, Lewis and Lowery, she said. She feels “spoiled” having had them for so long and regrets not engaging with them.

“But there were so many more questions that we could have asked. And now that we are in a critical moment, we miss that. How beneficial would it have been to have real conversations about organizing and work?”

Still, “Their work is done,” she said.

“Now it is time for other people to do the work.”

Hope in a new generation

That is why Cole, 83, is hopeful. She ran for president of the NCNW, on the promise to make the civil rights group more intergenerational, to train young leaders.

Training and education were things she was familiar with as the only person to serve as president of both of the country’s historic black colleges and universities for women — Spelman and Bennett College in Greensboro, North Carolina.

“People of our generation have the amazing ability to forget that we were once young,” Cole said. “My very cautious optimism comes in some measure of seeing young people out there in non-violent protests.”

While most of the protests have been peaceful, some have devolved into violence.

Just days after Lewis’ funeral, Lafayette, now 80, spent three days doing nonviolence training for 250 people in eight countries on Zoom through a program he started at the University of Rhode Island.

“We are keeping up the work the best we can under the circumstances,” Lafayette said.

The marathon

Sawyer, now a senior at Morehouse College, has led recent protests, megaphone in hand. He is only 22 years old, a year younger than Lewis was when he spoke at the March on Washington.

On Thursday, on the 55th anniversary of the signing of the Voting Rights Act, Sawyer and Hector visited the John Lewis Mural on Auburn Avenue. Later that evening, they hosted a mass meeting – via Zoom – about the historic legislation that was signed after intense pressure from civil rights leaders to protect the rights of Blacks to vote.

“I am focusing on being the voice of my generation and building a bridge between the next generation of activists and the baby boomer generation of activists who have been there and remind us that there is nothing new under the sun,” Sawyer said.

He has started The Tired Campaign to mobilize organizations toward change in local communities nationwide.

“There will never be another King, Lowery, Vivian or Lewis,” Sawyer said. “But what we can do is honor the work that they have done, and are doing. This is a long fight. This is a marathon and we are gonna be running for a long time.”

The King Generation

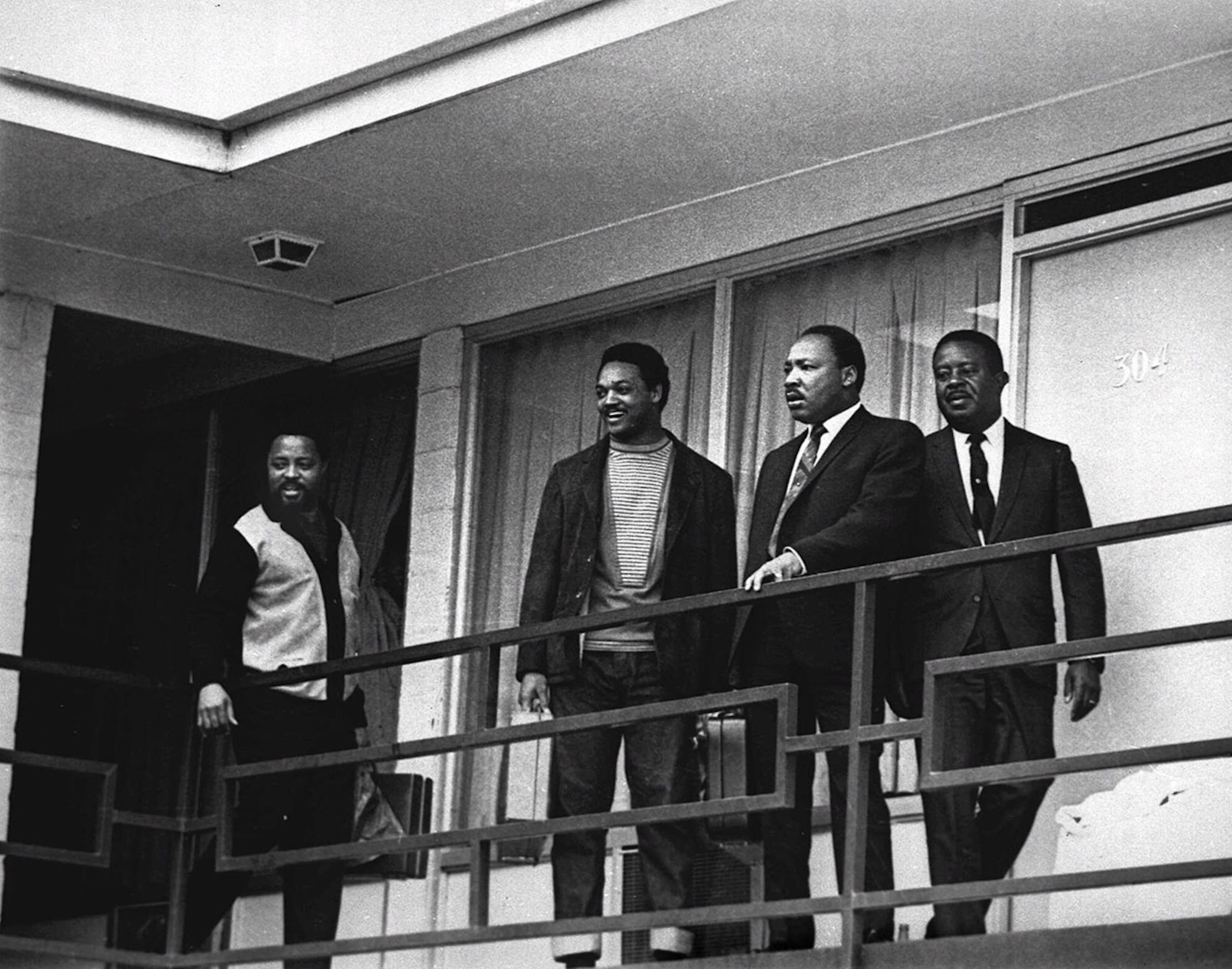

During his time as an active civil rights leader, roughly from 1955 until 1968, Martin Luther King Jr. surrounded himself with a dedicated group of advisors, who helped him strategize, marched with him, and who were at his side at his death. With the recent deaths of Joseph Lowery, C.T. Vivian and John Lewis, most of them are gone. In the photo illustration above, AJC designer Richard Watkins, re-imagines, King’s court. See the numerical key below.

1. The Rev. C.T. Vivian – 1924-2020: On Feb. 16, 1965, Vivian challenged Dallas County Sheriff Jim Clark by passionately articulating the rights for Black residents of Selma to be able to vote. Clark punched Vivian down the stairs of the courthouse. Vivian, who years later would receive a Presidential Medal of Freedom, stood back up and continued making his point.

2. The Rev. James Orange – 1942-2008: Standing well over 6 feet tall and 300 pounds with a booming baritone voice and strong views, Orange was described as one of the “real soldiers of the movement ... a gentle giant,” who kept things peaceful. He joined the civil rights movement in 1957 as a Freedom Singer and was hired in 1965 by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference as a field staffer.

3. The Rev. Joseph Lowery – 1921-2020: Known as the “Dean of the Civil Rights Movement” in his later years, Lowery integrated buses in Mobile, Alabama, months before the Montgomery Movement. He was one of the founders of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and its longest-serving president. After the historic election of Barack Obama, Lowery delivered the benediction at his inauguration.

4. Hosea Williams – 1926-2000: “Unbossed and unbought,” Williams marched alongside John Lewis on Bloody Sunday, where he was among the dozens who were beaten by Alabama state troopers. In 1970, he started Hosea’s Feed the Hungry and Homeless, which is still run by his daughter.

5. Ella Baker – 1903-1986: A force behind the scenes, Baker played the mentor role in the NAACP, then the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, working with W.E.B. Du Bois, Thurgood Marshall, A. Philip Randolph and King. Over Easter in 1960, she invited a group of Black college students to Shaw University to talk about activism. At the meeting, attended by John Lewis, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee was formed.

6. Coretta Scott King – 1927-2006: The wife of Martin Luther King Jr., she was by his side since they were married in 1953, until his death. Just months after his death in 1968, she started the Martin Luther King, Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change. In 1986, her efforts to keep her husband’s memory alive led to the establishment of the King federal holiday.

7. The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. – 1929-1968: The undisputed leader of the civil rights movement, King was at the center of nearly every major offensive. He delivered the landmark, “I Have a Dream,” speech at the 1963 March on Washington and won the 1964 Nobel Peace Prize. He was assassinated in Memphis on April 4, 1968.

8. John Lewis – 1940-2020: The “Boy from Troy,” earned his civil rights stripes as a member of the Nashville Student Movement and a Freedom Rider. He was the youngest speaker at the March on Washington and led marchers across the Edmund Pettus Bridge on Bloody Sunday. He represented parts of Atlanta for 33 years as a member of the United States House of Representatives.

9. Dorothy Height – 1912-2010: As the president of the National Council of Negro Women, focusing on gender issues, she was one of the powerful women in the movement. She also served as the national president of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority from 1947 to 1956.

10. Rosa Parks - 1913–2005: “The Mother of the Freedom Movement,” Park’s 1955 refusal to give up her seat to a white man on a Montgomery bus launched the modern civil rights movement. Martin Luther King Jr., an unknown 26-year-old pastor was chosen to lead the 381-day Montgomery Bus Boycott.

11. Wyatt T. Walker - 1928-2018: An early board member of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, he was also one of the founders of the Congress for Racial Equality. But he helped raise the SCLC to national prominence as the group’s executive director.

12. The Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth - 1922- 2011: One of the most vocal and fiery leaders of the civil rights movement, Shuttlesworth was a member of the SCLC and active in Birmingham. On Christmas Day 1956, his Birmingham home was bombed. The next day, he led 250 people in a protest of segregation on buses in Birmingham.

13. The Rev. Ralph David Abernathy – 1926-1990: King’s closest ally, Abernathy started with King in Birmingham and was with King on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in 1968 when he was assassinated. He succeeded King as president of the SCLC.

STILL MARCHING

Andrew Young: A key King lieutenant who went on to a successful life in politics and business. He became a United Nations Ambassador under President Jimmy Carter and a two-term mayor of Atlanta.

Jesse Jackson: Started the Rainbow/PUSH organization in 1971 before running for president in 1984 and 1988.

Bernard Lafayette: A founder of the Nashville Student Movement and SNCC, he went on to become a scholar and college president. He is currently the chairman of the SCLC board.

Diane Nash: As a student at Fisk University, Nash emerged as a key strategist with the Nashville Student Movement and SNCC.

Bob Moses: A member of SNCC, Moses is a co-founder of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party and was an organizer of the 1964 Freedom Summer. In 1982, he used a MacArthur Genius Grant to start the Algebra Project, a minority math-based teaching initiative that emphasizes community activism.