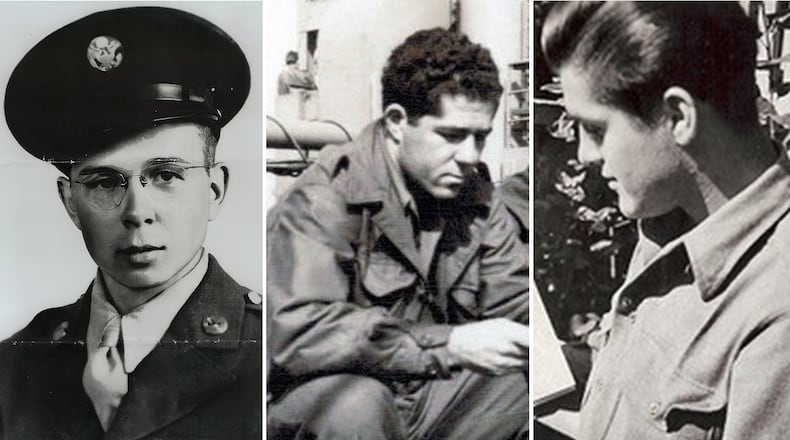

Alan Kinder narrowly survived an artillery attack in World War II. Hilbert Margol confronted the horrors of the Holocaust. And Andy Negra got so close to German soldiers during the Battle of the Bulge that he could hear their conversation.

All Georgia residents, the three are among dozens of WWII veterans who are traveling from across the country to Normandy in June to commemorate the 80th anniversary of D-Day.

Their trip will coincide with a state visit by President Joe Biden, who will appear in Normandy and deliver a speech about the importance of defending democracy. French President Emmanuel Macron and many U.S. legislators and military leaders are also expected to appear at some of the events.

But much of the attention will be trained on the surviving WWII veterans, a rapidly dwindling group. As of last year, there were just 2,362 of them still alive in Georgia, according to the National WWII Museum. Here are three of their stories.

‘Lucky breaks everywhere’

Alan Kinder was on his way to the Battle of the Bulge when he and some fellow soldiers took shelter in a three-story house north of Luxembourg City in December of 1944. As he prepared to go to bed, Kinder bent over to untie his shoes.

Though he doesn’t remember the blast, a German artillery shell struck the house, killing some of Kinder’s fellow troops in the attic. Knocked out, Kinder came to with a mattress on top of him. He was shaken but uninjured.

“It was just a stroke of fate,” Kinder said. “There were lucky breaks everywhere in my life.”

He was born in the Seattle area. His father helped manage a sewer pipe manufacturing plant and his mother stayed at home raising Kinder and his younger sister. When Kinder was 18 in 1943, he was drafted. His harrowing job in the U.S. Army: Working close to the frontlines to detect enemy artillery positions with microphone technology.

He could not see much when landed on Utah Beach late in the evening of Aug. 17, 1944, four months before the shell struck the house he was in.

As his unit moved inland, Kinder saw parachutes hanging from trees and the wreckage of glider planes from the allied invasion. As the Battle of the Bulge began, Kinder’s unit was told to pull back. Unnerved by the retreat, Kinder heard Germans had taken U.S. military uniforms from their American prisoners and were infiltrating Luxembourg.

“We couldn’t trust anybody,” he said. “It was a spooky time.”

After the deadly battle, Kinder’s unit camped in Belgium. It was snowy and cold. To build fires, the soldiers began pulling up farm fence posts. They gave the owner receipts.

Kinder remembers passing by women who had their heads shaved as punishment for fraternizing with the Germans. He saw German prisoners of war being marched past his unit. He remembers crossing the Rhine River on a pontoon bridge. German military pilots landed at an airfield so they could surrender to Kinder and fellow U.S. soldiers instead of the Russians. He remembers helping German farmers cut and stack hay and pick strawberries.

After the war, Kinder graduated from college and married. He and his late wife, Vaida, raised two daughters. Kinder worked as a ceramic engineer and then started a tiling business, working until he was 83. He will turn 100 on Jan. 26.

Kinder is looking forward to actually seeing the coast when he returns to Normandy for the first time in 80 years. He’s making the trip with the help of a charitable nonprofit called Forever Young Veterans.

His grandson, Justin Marsh, and 5-year-old great-grandson, Carter, recently visited him at his retirement community in Gainesville to deliver a framed commendation. Signed by Gov. Brian Kemp, it recognizes Kinder for his “life of dignity and honor” and for his “distinguished service to our nation.”

Kinder has another vivid memory. In December of 1944, he spent Christmas at a family-owned tavern north of Luxembourg City. Military policemen arrived with a small Christmas tree. They also brought wine and liquor from a wrecked German truck. The tavern featured a jukebox that played Christmas songs. Kinder called the experience “unimaginable.”

“It was the strangest experience,” he said. “It was like something out of Disney.”

The inseparable twins

Hilbert Margol and his identical twin brother, Howard, were traveling with their artillery unit to Munich in April of 1945 on a two-lane country road, when they detected a strong odor. They asked for permission to investigate. Their sergeant told them to move quickly.

The brothers hurried into the woods, soon reaching railroad tracks and some open boxcars. In one of the cars, they saw bodies. They ventured deeper inside the camp and spotted more bodies stacked like cord-wood.

The Margol brothers eventually learned they had stumbled upon the Dachau concentration camp, the infamous prison that held roughly 200,000 people, including Jews, Gypsies, Jehovah’s Witnesses and resistance fighters. More than 30,000 of them died from typhus and a variety of other ailments or were killed, according to Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Center in Jerusalem. Many were forced to build roads, toil in quarries and drain marshes. Others were subjected to cruel medical experiments.

“We just didn’t understand what we were seeing,” said Hilbert Margol, a 100-year-old Dunwoody resident who is married and has three children. “We just couldn’t comprehend it.”

It was personal for him and his twin. Both Jewish, the brothers had relatives in Lithuania who were murdered by Nazi sympathizers.

Hilbert Margol is visiting Normandy for the first time with a charitable organization called Best Defense Foundation, a nonprofit founded by former NFL linebacker Donnie Edwards.

Born in Jacksonville, Margol and his twin were inseparable. They both joined the ROTC and the U.S. Army Reserve while studying accounting at the University of Florida. After they were called to active duty in 1943, Hilbert was sent to the 42nd Infantry Division in Oklahoma, while Howard was assigned to the 104th Infantry Division in California.

Their mother wrote to President Franklin D. Roosevelt, asking for her sons to be united. The government granted her request, and Howard Margol was transferred to his brother’s unit.

Howard Margol told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution in 1987 that officers tried to scare him with “horror stories” about serving with relatives and the possibility of watching loved ones die in combat. He said he responded, “If something happened to my brother, I would want to be there, rather than hear about it 10,000 miles away.”

The brothers arrived in Marseille, France in January 1945. They served as artillery gunners. Hilbert Margol remembers the shock he felt when he saw the bodies of dead German and American soldiers lining the sides of the roads they traveled.

“You never forget that,” he said. “But as you move on through combat, it becomes just part of the scenery, so to speak. By the time we got to Dachau, it was more of the same. So it wasn’t that great of a shock.”

After the war, the Margol brothers went into the furniture business. Howard Margol died in 2017 at 92. His brother has publicly shared their story many times, including at high schools and places of worship.

Asked about people who deny the Holocaust, Hilbert Margol repeated something he has said many times before: “I hope and pray that the offspring of those who hear my story will outlive the offspring of the deniers.”

‘Keep going’

Andy Negra was riding in a half-track vehicle through Germany with his Army unit in the spring of 1945 when he saw a camp surrounded by a tall fence.

“I can remember a couple of the prisoners that were inside there walking and talking to one another,” said Negra, a retired U.S. Agriculture Department worker who lives in Sautee Nacoochee near Helen.

Later, men from Negra’s unit visited the sprawling site northwest of Weimar and found more than 21,000 people inside. It was the notorious Buchenwald concentration camp, where the Germans had imprisoned about 250,000 people from across Europe and murdered at least 56,000 of them, including about 11,000 Jews, according to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Negra has other vivid memories from the war: Celebrating Christmas Eve in France with turkey, stuffing and cranberry sauce. Sleeping in a bowling alley in Luxembourg. Riding in tanks.

He was drafted in 1943, the same year he became the first in his family to graduate from high school. The son of immigrants from Central and Eastern Europe, Negra was born near Avella, Pennsylvania. His father worked in the coal mining industry, while his mother raised Negra and his three siblings.

After he was drafted, Negra trained in North Carolina and then headed to Wales in February of 1944. Attached to an artillery battalion, he landed at Utah Beach on July 18 of that year.

As he rode to the Battle for Brest in northwest France, Negra’s column came under attack from German fighter planes. He scrambled out of his half-track and took cover behind a stone well. The German fire split the log holding a bucket over the well, but Negra was unscathed.

His unit moved on to other missions in France before crossing into Luxembourg and then Germany. Along the way, Negra worked in his unit’s survey section, helping locate enemy positions for U.S. artillerymen. He also rode in tanks a few times. During the Battle of the Bulge, a fellow tanker admonished him: “Don’t say anything because the Germans are all around you. And if you make any noise, you are a goner.” One night, the German soldiers were so close to his tank that Negra could hear them speaking to one another.

At the end of the war, Negra participated in the allied occupation of Berlin. He returned home and was honorably discharged in December 1945. Negra’s wife of nearly 71 years, Viola, died in 2017 at age 90. They raised a daughter and two sons.

This will be Negra’s second year in a row commemorating the anniversary of D-Day in Normandy. Like Margol, he is traveling to France with the Best Defense Foundation. Negra still remembers last year’s parades, bands and the gifts he was given by adoring French citizens.

“It was an amazing thing. In every town we went, the streets were lined up,” Negra said. “No matter where I went, somebody wanted to shake your hand.”

Negra turned 100 on May 28. His recipe for longevity includes keeping a positive attitude and not harping on your own misfortune.

“If you have a problem, solve it. And if you can’t solve it, do like you are crossing the street and you have a puddle of water in front of you. Either go through that water or around the water or jump over the water. But keep going.”

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured