50 years of Loving: Interracial couples reflect on Supreme Court decision

Americans today mark the 50th anniversary of Loving v. Virginia, the U.S. Supreme Court decision that legalized interracial marriage in the United States.

The decision voided a Georgia law, in force since 1750, that made it unlawful for any nonwhite person to marry any white person.

» RELATED: Interracial couples that changed history

» RELATED: A timeline of Loving v Virginia

» RELATED: The ‘fake news’ history of the word ‘miscegenation’

Census figures show that Georgia today is home to nearly 11,500 interracial couples. The average age of these couples is 49. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution contacted several of them in metro Atlanta, covering a range of ages, to ask them what the Loving decision has meant to them and what they’ve learned in their relationships. These are edited transcripts of our interviews with them.

Sam and Marti Hagan, East Lake

Married: 1974

New Yorker Marti Ellis met Georgia native Sam Hagan in 1973 when she was managing the Lake George Opera Festival in upstate New York and he had a summertime contract to sing at the resort town.

He opened his mouth at a rehearsal and she fell in the love. The feeling was mutual. But bringing a white wife back to Georgia could have been problematic.

“Sam’s family was a little concerned because I wasn’t Seventh Day Adventist, but at least I was a Christian,” she jokes now.

» RELATED: Tenor Sam Hagan has been the sound of the holiday season

There were also archaic laws on the Georgia books forbidding interracial marriage. “Certainly, if it wasn’t for the Supreme Court case that happened in 1967, Georgia would not have been an option for us,” said Marti, 73. “So the Loving decision played a huge factor in our lives.”

She continues to work in opera management and, since retiring from his first career as a biology teacher, he has continued to sing. They’ve made beautiful music together.

Sam has seen bigotry, but on the whole their relationship has been accepted by friends and acquaintances and even by those they meet in their frequent travels around the country and around the world, whether at a B&B in South Georgia or a hotel in Iceland.

This might be because they’re not looking for it. “If you go out there looking for trouble, then you get it. And you react to it, and it bothers you,” said Sam, 75. “To me, ignoring it, or not even being aware of it, has helped us not care about it. …

“I’ve been in almost every national park in the system,” he said. “The kind of people that you meet in places that we like to travel to are typically people who are accepting of our relationship.”

Perhaps their good experience resulted because their sensitivity is dialed way back. “It would have to hit me in the face,” said Marti.

Their advice for a lasting union?

Sam: “A happy marriage is one where you listen to each other. The biggest thing is forgiving. Forgiving and forgetting.”

Marti: “You have to be committed and then whatever obstacles or struggles, whether you’re in a same-race marriage or an interracial marriage, if you’re committed you’re going to find your way through. And you’re not going to be committed if you’re not in love.”

Chris and Michelle Render, Hampton

Married: 2009

For everything that Michelle Render gained when she married her husband Chris, there were things that she lost.

“I have family who will walk out of the room when we show up,” Michelle said. “We haven’t seen some family members in six years.”

Some 50 years after the Loving case was decided, the idea of interracial marriage is still not universally accepted. Especially in the South. But that doesn’t seem to bother the Renders.

“I heard a little bit about the case, but it didn’t play a part in why I became friends with him,” Michelle said. “I don’t look at people for their color, I look at people for their heart. I didn’t go out and say I want to marry a black guy. He was the first, he was the only, and I couldn’t be happier. I fell in love with his personality, his heart. He has the biggest heart out of anyone I know.”

Chris said he heard about the Loving case. But never read it. He missed the movie last year, but remembers watching the documentary that inspired the movie about the Virginia couple.

“These people had to give up a lot to get to what they loved,” Chris said. “I remember thinking, if I loved someone that much, or if someone loved me that much, it is all worth it.”

The couple, who met innocently enough at work 14 years ago, were married on Aug. 19, 2009.

“Color never played a part in why I fell in love with him. We had so much in common. We were very family oriented. We really wanted to be around positive people,” Michelle said. “From the moment I met him, even when I was having a bad day, he would say, ‘That’s OK, Michelle. You alive, you’ll be OK.’ We had a bond that was almost instant.”

“For men, we are sight driven. And she was the most beautiful thing that had ever graced my eyes,” Chris said. “I was moved by her. And in talking to her, she drew me in even more.”

Now with two children — 6-year-old Madeline (a budding actress, whose movie “Megan Leavey,” opened Friday) and 5-year-old Cameron — the Renders have settled in nicely in Henry County.

Their kids are in good, culturally diverse schools and they have lots of friends.

But everything has not gone smoothly.

“I’m not going to lie, there are parts of my family that still do not agree with it,” Michelle said. “So I have had to separate them from my life.”

Luckily, their closest family members have always been cool. Chris’ older brother married a Filipino woman years ago. And Michelle’s mother actually knew Chris before she did.

“She always says, ‘I met him first. He is mine,’” Michelle said.

And they still live in the South in a county that is now embroiled in a tense fight over the flying of the Confederate flag. Michelle tells the story about walking into a restaurant with her husband and her parents and the hostess walking up and asking if they were a party of three, completely overlooking Chris.

But Chris said he takes it in stride.

“It is one of those things where we say, keep the blinders on and keep moving. I am here with her and if you don’t like it, that’s on you, because I am happy,” Chris said. “If you ask me a question and I give you an answer, you can’t use ignorance anymore. I want people to see that we are people who love and care about each other. That is the only thing that matters.”

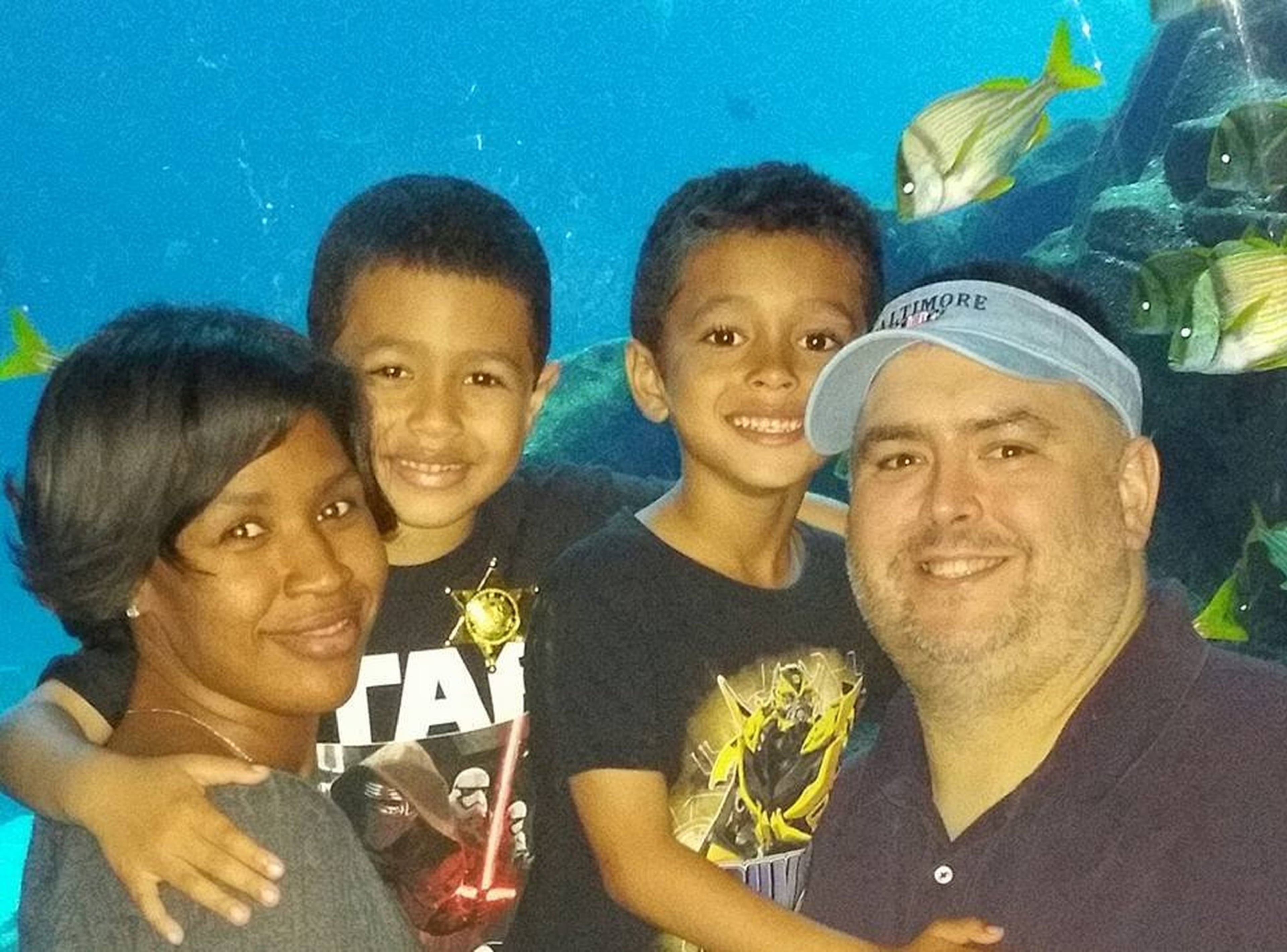

Wayne and Tareka Haydin, Lawrenceville

Married: 2009

Wayne J. Haydin Jr. gets emotional when he talks about the first time he read about the Loving case. It was 2006 and he was in his first year at the Southern University Law School.

“The thing that touched me the most was that it wasn’t so far removed; I wasn’t reading about the Civil War. Mr. Loving was alive when I was born, and when I was reading the case, Mildred Loving was still alive,” Wayne said. “When something affects you personally like that, it hits home. So I was one generation removed from a time when I couldn’t marry the young woman sleeping in the other room.”

In 2003, three years prior to reading about the case, Wayne met Tareka Brisco on the campus of Southern University, a historically black college and university (HBCU) in Baton Rouge, La.

On May 30, 2009, three years after reading about the case, the couple got married.

“I was attracted to his personality, and he is a looker,” Tareka said. “He wants to experience the world and everything around him.”

In the early 2000s, their world was Louisiana. Wayne grew up in New Orleans and only attended all-black schools.

“I have never actually dated a white girl. Not to say that I wouldn’t, but there weren’t many into the same things I was into,” Wayne said. “In New Orleans, once you dated a black girl, you were viewed as tainted. So even if I wanted to date a white girl, chances are I was going to be viewed as not eligible. But that was fine with me. I am good where I am.”

Most of his teachers had attended Southern University, so it wasn't a stretch for him to attend. But it was a stretch in 2003 when he was elected Student Government Association president — becoming the first white person in the school's then 123-year history to hold the office.

The first person to congratulate him was Tareka Brisco, who was a freshman and a native of Baton Rouge.

“I thought that was important to introduce myself and congratulate him, because a lot of people were not happy that he was elected,” Tareka said.

“When she introduced herself, I was like, ‘How you doing?’” Wayne said. “She had a certain spunk and spark about her. I loved the way she carried herself. The way she talked. And she had a BS detector. I knew she was the one when she got me to break down my walls and realize my full potential.”

Tareka said when they started dating and decided to get married, she wasn’t familiar with the Loving case, but did her own research around Baton Rouge. So she talked to every interracial couple, from every walk of life, she met.

“I felt it was important to get an insight into their experiences and learn how they overcame obstacles. How they handled the looks, stares, questions and assumptions. How they raised their kids,” Tareka said. “I wanted to get a better understanding and learn how to handle myself appropriately. It made me feel that we were not out there by ourselves.”

But there were still issues. The couple initially settled in Baton Rouge, where Tareka said “interracial relationships are not the best.”

“I was afraid to raise kids in an environment where there were so few kids who looked like them,” Tareka said. “I was afraid of close-mindedness.”

The couple have two sons: Wayne III and David Christopher II.

In Baton Rouge one night, Wayne rushed Wayne III to the doctor because of a rising fever. A friendly enough white nurse came out to play with Wayne III. Then she paused and looked at Wayne.

“She said to me: ‘And what is mom?’” Wayne recalled. “I just looked at her and said, ‘Mom is my wife.’ And that is the end of that.”

The family moved to Atlanta on New Year’s Eve 2012, settling in Lawrenceville. Compared to Baton Rouge, it has been like night and day, they said.

“When we moved to Atlanta, we weren’t looked at or stared at,” Tareka said. “We had a positive vibe. We saw a lot of interracial couples and they seemed comfortable here.

“Being an interracial couple doesn’t define our relationship. It doesn’t define the narrative,” Haydin said. “Obviously, people notice, but I truly believe that when people see and know us, they don’t see us as that interracial couple, they see us as the Haydins. I want you to see color. But I want you to not care.”

“I just want people to know that we are a multiracial family, but just like everyone else,” Tareka said. “We fight and we love just like other families. We are just different colors.”

Note: Commenting for this article is being moderated by AJC editors.

New this summer: The AJC covers race

Georgia is in the midst of a dramatic transformation in which minorities will become the majority in about 15 years. The AJC is covering that story in all of its manifestations -- digging deep for data that expose the trends and examining how our daily interactions affect one another.

» Interactive: Watch as Georgia transforms before your eyes

» Read: The new face of Cobb County