The fight for a cure

Decatur resident Norman Hulme chose an unconventional approach to do his part in the fight against the coronavirus pandemic.

The 65-year-old Emory University employee volunteered in a trial vaccine at the school, getting a small injection of a compound with a portion of the disease about two weeks ago.

Emory researchers anticipate his body will fight the disease, similar to the process of getting a flu shot. He’s one of several dozen trial patients, one of the few volunteers older than 55, the age group physicians believe is more susceptible to COVID-19.

» MORE: Plasma therapy could be ‘liquid gold’ for COVID-19 treatment

“I think we all feel a little bit helpless,” Hulme, explaining his decision, said in a telephone interview last week. “We all want to do something.”

A potential vaccine from this study, and others being pursued in Georgia, could take a year. It’s a daunting timeline but the race is on to find treatment and vaccines at Georgia’s research universities.

There are about 20 ongoing studies at the schools, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution found through a review of published documents and interviews with researchers. Other work is being done, but researchers aren’t discussing it until they feel there are developments worth sharing, said Susan Shows, senior vice president of the Georgia Research Alliance. There are about 90 vaccine studies, the World Health Organization says.

One therapeutic study involving Emory sparked enough hope last week when federal health officials said the research of an experimental drug called remdesivir showed enough promise that they authorized it as emergency treatment. Emory has 103 patients in the 1,063-patient study, more it says, than any of the 68 sites involved in the research. Georgia State's use of auranofin, an arthritis drug, as a COVID-19 treatment has also piqued the curiosity of fellow researchers.

Therapeutic research is ongoing at both state universities and other institutions, including Georgia State, Mercer University, the Medical College of Georgia and Morehouse School of Medicine. Shows and others say the research is the largest collaborative effort she’s ever seen by Georgia’s universities to combat one disease.

Some researchers at different schools are working together, and in several cases, they are working with local and international companies that provide equipment and other resources, typically in exchange for a share of future profits from manufacturing the drugs.

“This is a pretty interesting and intense network, which shows you the cooperation by the state and local universities,” said Dr. Ted Ross, director of the University of Georgia’s Center for Vaccines and Immunology and Georgia Research Alliance Eminent Scholar.

Federal officials have a multi-step process for any vaccine to be approved. It includes clinical trials, inspection of the manufacturing facility and presentation of findings to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration's Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee. The FDA can require a manufacturer submit the results of their own tests for potency, safety and purity for each vaccine lot. The FDA can require each manufacturer submit samples of each vaccine lot for testing.

After approving a vaccine, the FDA continues to oversee its production to ensure safety. Monitoring of the vaccine and of production activities, including periodic facility inspections, must continue as long as the manufacturer holds a license for the vaccine product.

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

THE RESEARCH

Here's some of the research taking place at various Georgia universities and schools.

⁃ Emory University is a leading partner on worldwide treatment research that has shown quicker recovery times and smaller percentages of death rates. Researchers stress the results are preliminary and need more study. More than 1,000 patients are involved, including 103 at Emory.

⁃ A team at the University of Georgia, led by Professor Biao He, is working on a vaccine he hopes will be ready for FDA approval by the end of the year. The vaccine is based on research tested in dogs to mount a defense against the spike proteins in the coronavirus that causes Middle East respiratory syndrome. The novel coronavirus attacks the human body in a similar fashion, through spike proteins.

⁃ Morehouse School of Medicine researchers are working on an herbal treatment used about 15 years ago to treat HIV patients in Senegal who they say are now symptom free. The plant-based extract, they say, has little to no side effects. The team is working with the Southwest Research Institute, based in San Antonio, on the research.

⁃ Georgia State University last month released research on auranofin, a rheumatoid arthritis drug it says made about 95% of the virus disappear in 48 hours through tests of COVID-19 cells. Auranofin is FDA-approved and has been used as a potential treatment for diseases such as cancer and HIV. The team is planning more testing and mixing it with other drugs to determine if that will strengthen its effectiveness.

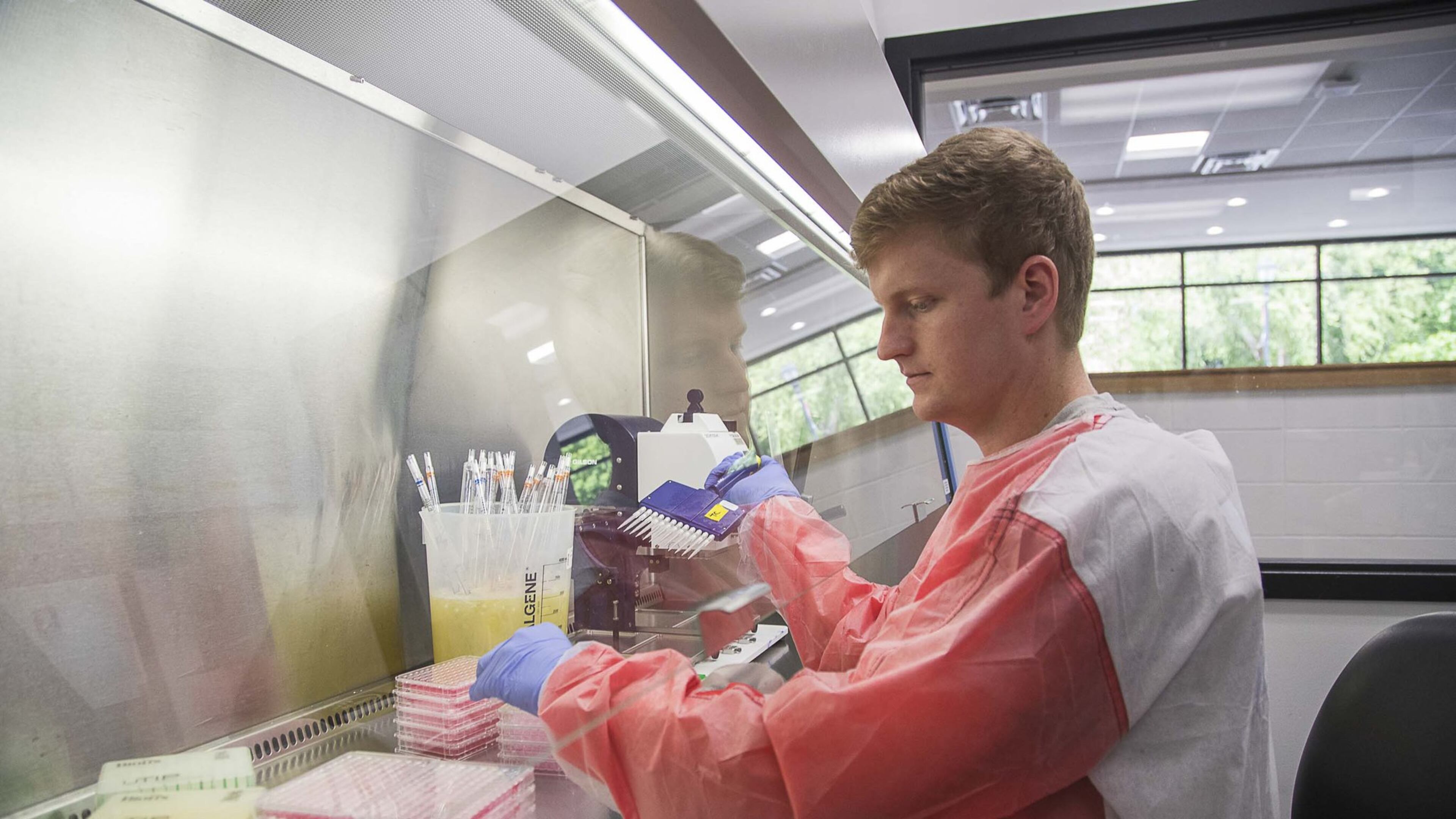

⁃ Emory University is doing human clinical trials on a potential vaccine with Kaiser Permanente Washington. They are injecting portions of the genetic material that causes COVID-19 but cannot cause the infection. The process is similar to a flu shot. Emory will see how effective the immune system of each participant is in generating antibodies against the virus.

Most of the campus research is in the early stages. Much of it did not start until the disease landed on American soil.

Most of the work on Georgia campuses involves treatment. It includes the use of drugs already approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, such as auranofin, experimental drugs like remdesivir, and taking blood plasma from COVID-19 survivors and injecting it in current patients for treatment.

The Morehouse School of Medicine team is working with Prometra, a Senegal-based company with 28 sites worldwide, on a herbal treatment used to treat HIV patients in the west African nation they say are symptom free. COVID-19 attacks the body similarly to HIV, the Morehouse team said, so they believe the treatment could be effective.

“The first line of defense is to develop treatment,” said Vincent Craig Bond, professor and chair of the medical school’s department of microbiology, biochemistry and immunology.

Dr. Virginia Floyd, an associate professor in the school's department of community health and preventive medicine, said she feels the need for treatment is critical. It's personal for the team at the historically black school. They noted the disproportionate percentage of African Americans diagnosed and dying from the disease.

“Our timeline (for finding treatment) is yesterday,” Floyd said.

In Georgia, the vaccine research is being led by UGA and Emory, which has among the largest vaccine research centers in the nation. The work is being funded by federal research dollars and through private partnerships. President Donald Trump signed a bill in March that included $3 billion for vaccine and therapeutic research. The vaccine research that Hulme is participating in, through a partnership with Kaiser Permanente Washington, is being closely watched.

Emory’s remdesivir work

Any vaccine or treatment must by approved by the FDA. Vaccine research is done through clinical trials, first using animals, to determine does it work, is it safe and does it have limited side effects. Most clinical trials fail, but the hope is something will work with so much research underway across the globe. There’s no current vaccine or federally approved treatment for the disease.

The animal rights group, PETA, has concerns about some research. PETA wrote a letter Monday demanding Emory stop all experiments until it can show that no monkeys have been exposed to or infected with COVID-19. Emory officials said Yerkes National Primate Research Center personnel are taking precautions, including wearing personal protective equipment when in animal areas and social distancing masks in common areas, working split schedules to reduce the potential for disease transmission and watching for any signs of respiratory illness in the animals.

Many of the drugs being researched have been used for studies of horrific diseases such as Ebola, H1N1 and Middle East respiratory syndrome. For researchers, finding something to manage or cure this disease is what they’ve been trained to do. It’s their moment.

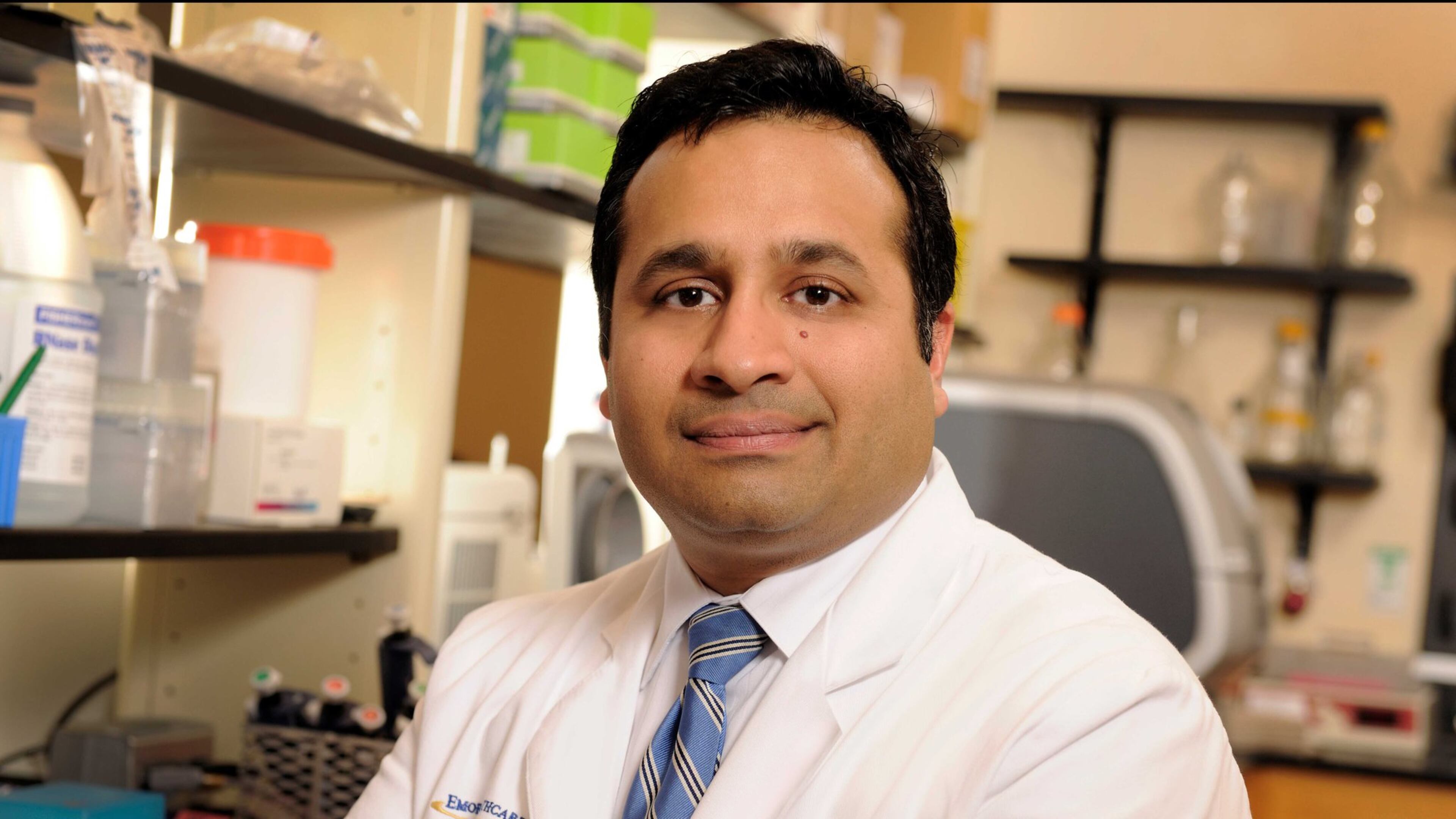

For one of those researchers, Emory’s Dr. Aneesh Mehta, there’s little time for rest.

A husband and a father of two young children, Mehta has had four days off in the past two months. Mehta, an associate professor of medicine in Emory’s division of infectious diseases, is part of the global team doing research of remdesivir, which is designed to block the infection of healthy human cells. The study patients received 200 milligrams the first day and 100 milligrams a day for up to 10 days. Last week’s preliminary study showed the median time to recovery was 11 days for patients treated with remdesivir compared with 15 days for those who received a placebo. The mortality rate for patients who received remdesivir was 8% versus 11.6% for the placebo group, Emory said.

Emory is also determining how remdesivir works with other drugs to combat the disease. Mehta cautions their remdesivir work needs more research. Separate remdesivir testing by Chinese researchers has found less positive results. The Chinese study had fewer patients.

The challenges

As the nation completes its second month in a shelter in place from the pandemic, it feels like the disease has been here forever, but there is still little researchers know about COVID-19 and there are questions, like whether cases will spike again this summer or fall.

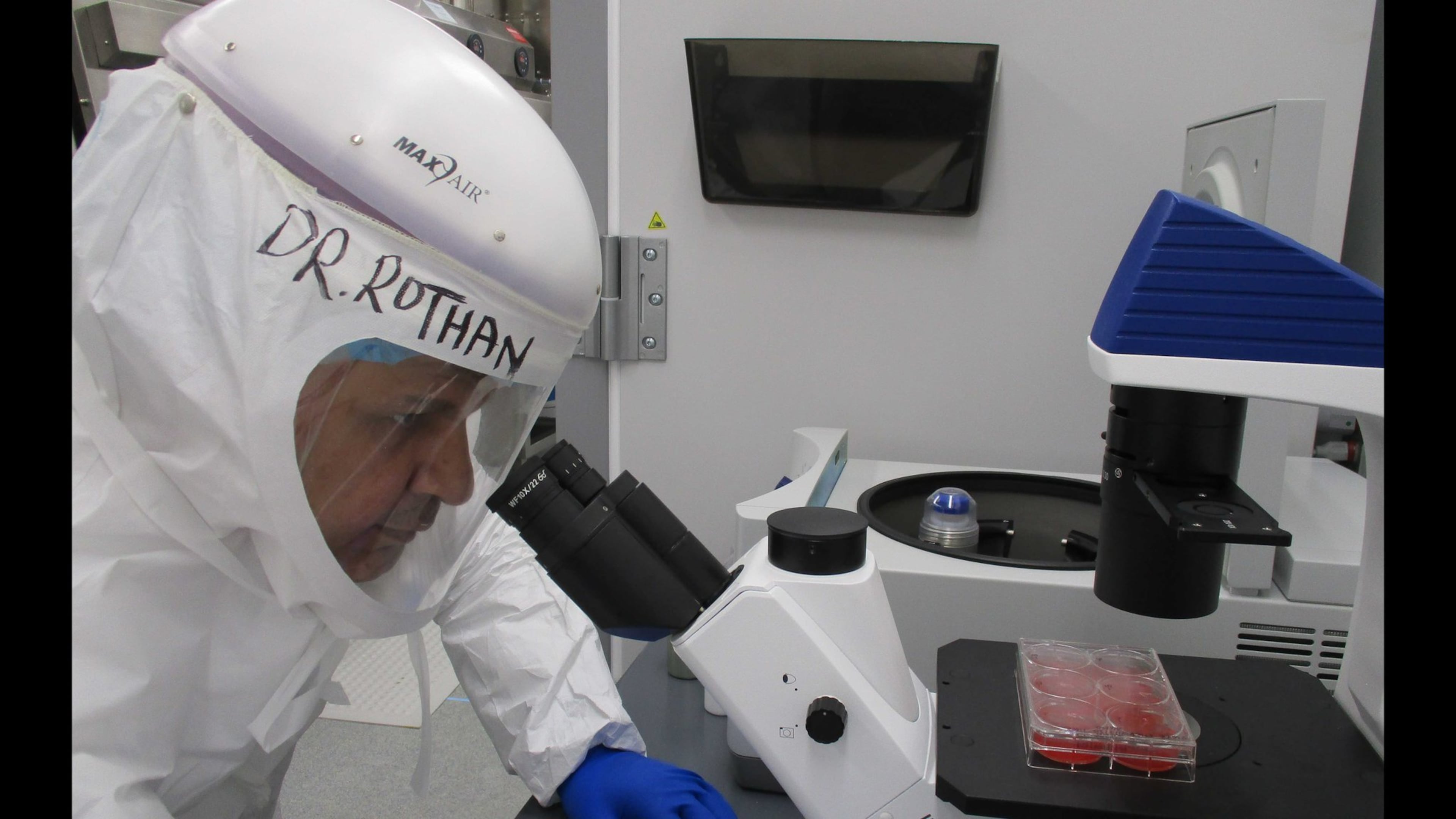

Ross, who has been doing vaccine work for 25 years, has similar questions, and a practical concern. His team at UGA, which includes graduate students, is on pace to run out of some personal protective equipment by mid-June.

“If we run out of PPE, we have to stop our work,” Ross said before leading a reporter and photojournalist inside a research lab.

Ross said the vendor they use is the same used by many researchers. PPE donations are welcome, he said.

Shows is creating a list of needs from researchers. They include high-resolution microscopes and imaging equipment. They hope to get state funding for some items when the new budget year begins July 1. The Morehouse School of Medicine team said it could use more lab space, researchers and money. Drug Innovation Ventures at Emory (DRIVE), a not-for-profit biotechnology company owned by the university that was created to discover and develop antiviral drugs, created a GoFundMe page for fundraising.

‘A long road’

The UGA teams working with Ross operate in shifts. Some from 8 a.m. to early afternoons. Others from noon to dusk.

“Every day is a very long day right now,” said Ross, who often ends his comments with a chuckle.

The labs are often loud and noisy. Many team members are graduate students, eager to help and to do something productive away from home.

UGA announced in late September it is leading a federally funded effort to develop a new, more advanced flu vaccine to protect against multiple strains of the virus in a single dose. Ross, the lead researcher, is now trying to apply the same strategies to create a respiratory vaccine for influenza and the novel coronavirus.

Ross is studying three potential vaccines, using computer algorithms to determine the best approach. One is with EpiVax, a Providence, Rhode Island-based biotech company. Another is with Vaxine, an Australia-based biotech firm. The third is in house.

The teams are hoping its vaccine will stimulate the body to make antibodies that will neutralize the virus when a person is exposed. Ross said it will be several months before his team has results that show which vaccine may work best. He believes it will be about a year before they have a serious vaccine contender. Finding a vaccine, he said, would be “fantastic,” but he tempers expectations.

“It’s a long road,” he said.

Emory researchers speak similarly about timelines. Dr. Rafi Ahmed, its vaccine center director, said it is trying to create a vaccine with cellular and humoral immunity capabilities, meaning it can kill the virally infected cells and can create a good antibody response. Ahmed said it may take time, but he understands the need for a breakthrough.

“We badly need a vaccine,” he said.

Hulme, the Emory vaccine patient, learned about the study through the neighborhood app Nextdoor, and from his ex-wife, who encouraged him to volunteer.

Hulme did his homework and went through the screening process, which included giving blood samples. His second and final injection is scheduled for mid-May.

So far, he said, no side effects.

“To take part in one small piece of this is a honor,” he said.