Preparing for surge, hospitals limit visitors, reschedule surgeries

Some Georgia hospitals are already straining to cope as a surge of people concerned they may have the coronavirus swamp emergency rooms and more beds are filled with suspected cases.

The state Department of Public Health on Monday increased Georgia’s count of confirmed cases to 121, but that number is expected to swell as testing, which is still very limited, becomes more widely available. Already, one Georgia hospital is awaiting on test results for more than 50 severely ill patients.

Rationing is sweeping the system. Hospitals from Gainesville to metro Atlanta to Albany have stopped elective surgeries in order to free up beds. Hospitals know they don’t have enough masks and protective equipment for the long haul that they expect with this coronavirus.

» COMPLETE COVERAGE: Coronavirus in Georgia

» RELATED: As hospitals fight to keep up, they tell mild cases not to seek tests

On Monday, Emory Healthcare, which operates 10 hospitals and numerous clinics around metro Atlanta, started a two-week postponement of all elective surgeries and some procedures such as colonoscopies to free up resources to combat the outbreak.

“We are preparing for the long run and looking at this as a challenge that will be one of the biggest national challenges most of us have seen,” said Dr. Jonathan Lewin, CEO of Emory Healthcare.

Piedmont Healthcare on Monday announced it is also cancelling elective procedures to conserve resources and limit potential exposure for staff and patients. Kaiser Permanente, which operates 25 medical clinics across metro Atlanta and one in Athens, has temporarily shuttered nearly half of its clinics to consolidate operations and allow it to adequately isolate patients, when needed.

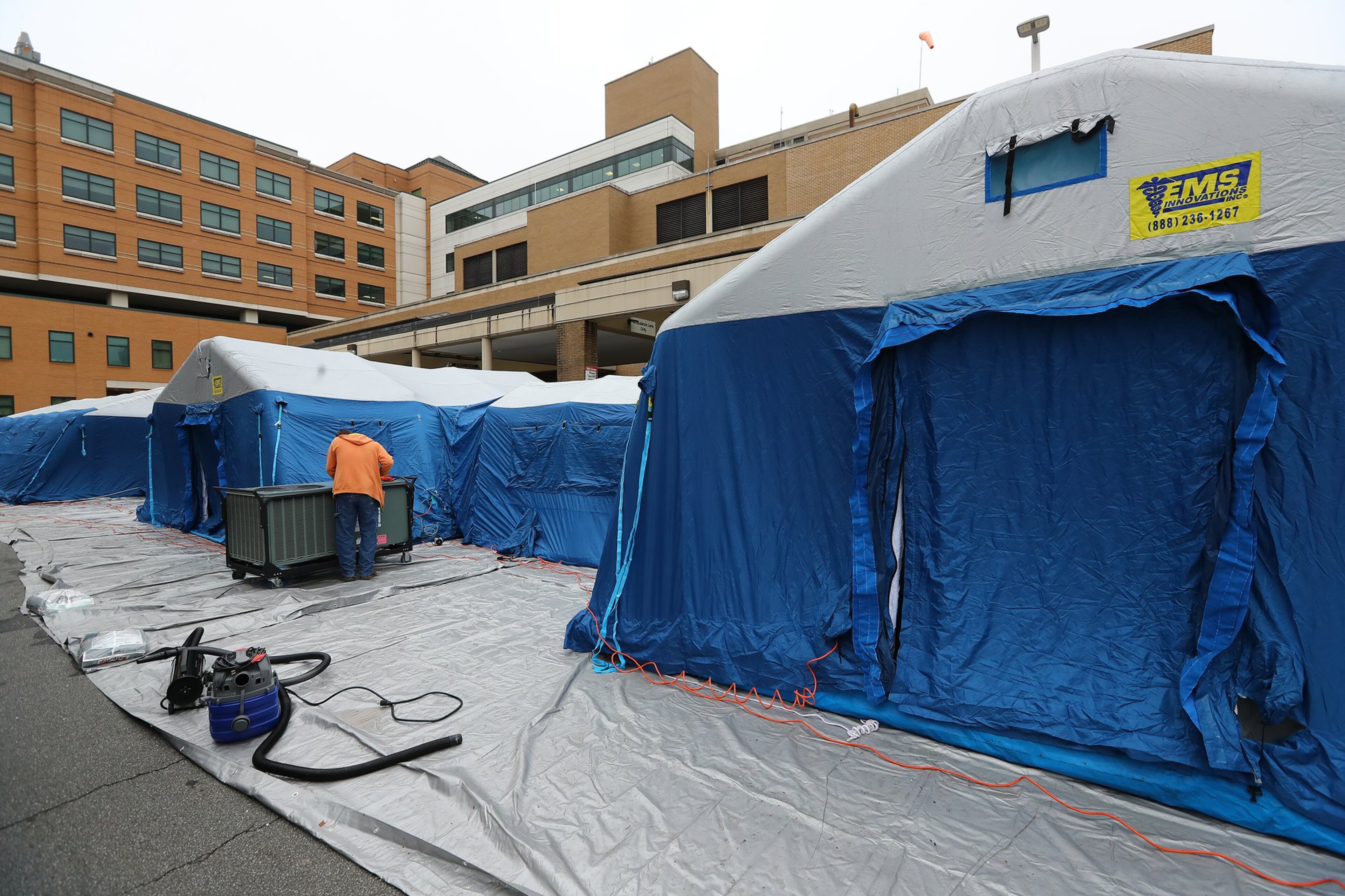

Some Georgia hospitals, including Wellstar Kennestone, have set up tents outside for triage or testing. Hospitals are also banning most visitors and screening those who do enter, even taking their temperatures.

Drastic measures across the health system reflect the crisis mode that has taken hold statewide, as frontline healthcare workers step through the doors of their workplaces at all hours and thousands of other Georgians are seeking shelter in their homes.

“Our frontline people are truly heroes,” Lewin said. “They’re working harder than anyone has ever worked both to prepare (and treat patients). We recognize this is the beginning of a surge and will get more challenging before it gets better.”

Supplies running short

Phoebe Putney Health System may be the canary in the coal mine. Its flagship hospital in Albany, a city anchoring southwest Georgia, has exploded with possible COVID-19 patients in the last five days. The hospital now houses 65 patients who’ve either been diagnosed with the disease or are waiting for tests to confirm the diagnosis. That’s just the inpatients; 115 more with less severe symptoms are at home, waiting for test results. The hospital released the numbers along with a plea to speed up testing.

Phoebe Putney’s other hospitals have more cases.

» RELATED: Georgia's first senior care coronavirus cases reported

» MORE: Nine doctors test positive for coronavirus, according to Gupta

The hospital system is well funded and connected for a rural one. But, says CEO Scott Steiner, they’ve run through five months’ worth of supplies in six days. They’re good for another five more days, he thinks.

“We might have thought we were overprepared,” Steiner said, looking back at the system’s years of disaster planning. “But you just can’t believe what we went through from a supply standpoint.”

“This event is unlike anything anyone has ever seen,” Steiner said. “You can throw in SARS and H1N1 and Ebola. There was Hurricane Michael – that was a big deal. But the thing is, Hurricane Michael came and went, and then you kind of pick up the pieces. We’re what, six days into this here. And it doesn’t appear to be slowing. Is it only a matter of time till all others feel the same?”

The system has identified employees who are willing to sew masks if there’s nowhere else to turn. They’ve turned to the connections of members of their governing board for other help. Bleach may be a problem; they’ve got friends in the chicken factories lined up to supply it. Gowns are already a problem, but someone found restaurants willing to hand over some boxes. Community volunteers picked up and delivered them.

"Our frontline people are truly heroes. They're working harder than anyone has ever worked both to prepare (and treat patients). We recognize this is the beginning of a surge and will get more challenging before it gets better." —Dr. Jonathan Lewin, CEO of Emory Healthcare

Healthcare workers are being spread over new duties. As of Monday the Albany hospital has set up a drive-through screening for coronavirus, where workers swab patients’ nose and mouth while they sit in the car. Eight or nine nurses are staffing a telephone line to screen those who call in for the service.

The hospital isn’t strained just because of the number of patients but because of the added burden of treating patients needing isolation. Each time they move or leave, that space needs a “terminal cleaning” that takes more time. Every hospital is used to a certain percentage of these, but now there are more.

In addition, Phoebe Putney has closed down its gym and converted it into a daycare space for employees’s children. On opening Monday, 196 kids were signed up.

“I’m telling you,” Steiner said, “if this really blossoms, you’ve seen nothing yet.”

Some wary

Part of the problem across the state is that people worried about their symptoms are crowding into emergency rooms seeking testing. But the state is still largely restricting testing to those with a doctor’s order and serious symptoms. From March 5-15, the Department of Public Health processed only 447 tests.

“This rush on the emergency departments is having a big impact on available supplies as we have to use a full set of personal protective equipment — mask, gloves, glasses, gown and in some cases face shields,” said Anna Adams, vice president of government relations with the Georgia Hospital Association. “Each time we have to use PPE on a patient who isn’t sick it takes resources away from current and future patients who are very sick.”

People with mild symptoms should not be rushing to the hospital or an urgent care center, said Dr. Aneesh Mehta, associate professor in the Division of Infectious Diseases at Emory University School of Medicine.

Meanwhile, the coronavirus outbreak prompted others to stay away from hospitals.

Terri Lynne Willis, who had a liver transplant 28 years ago when she was a teenager, had important doctors’ appointments at Emory University Hospital next week. After talking to her doctor, she decided since she is stable, it’s too risky to go a hospital.

Willis, of Douglasville, said she’s always on guard and avoids crowds during flu season. Now, she’s decided to hunker down at home for at least two weeks.

“I’ve decided it’s better to be safe than sorry,” said Willis. “If I get sick with this coronavirus, this is the thing that could kill me.”

Conserving resources

Almost every hospital is focusing its staff and resources on urgent needs.

Northside Hospital said any of its planned surgeries that could safely be postponed for two weeks would be. Grady is postponing elective surgeries, according to a staff email.

Piedmont explained that cancelling elective procedure would limit potential exposure for staff and patients, while also helping to conserve supplies and hospital beds. “Moreover, it allows us to focus on our priority, which is getting past this pandemic and helping the patients who need us during this time,” officials said in a statement.

Wellstar, which operates 11 hospitals in metro Atlanta, confirmed Monday that it is “treating patients diagnosed with COVID-19” but would not say how many or at which hospitals. Wellstar Kennestone Hospital, which treated the first Georgia patient to die of COVID-19, said the tents set up outside its facility Sunday were there “to more efficiently serve patients who are being tested for COVID-19.”

Kaiser Permanente, which serves 300,000 members in Georgia, acknowledges its decision to close some of its smaller clinics and consolidate operations may seem counterintuitive in light of the outbreak, said spokesman Kevin McClelland.

But its larger clinics have isolation rooms and are better able to manage the increased safety protocols necessary, he said, and consolidation also helps conserve protective equipment. Many elective and non-emergency procedures are being postponed and services that can be provided off-site are being conducted through phone calls, emails or virtual visits.

“This is so we can reduce the risk to our members,” he said. “If you need in-person attention we are absolutely there for you.”

He said the clinics could reopen during the crisis if they are necessary to serve their members.

“We just have to keep reevaluating it,” he said.

Identify, Isolate, Inform

Many hospitals around the country use a system called “identify, isolate and inform” to protect healthcare workers and other patients from possibly-infected individuals arriving at a hospital with a communicable disease such as the coronavirus, said Dr. Aneesh Mehta, associate professor in the Division of Infectious Diseases at Emory University School of Medicine

The first critical step is identifying people literally at the front door of an emergency department.

“We have signs up that point patients toward a mask if they have symptoms of a respiratory illness such as coughing or sneezing or a fever so that they put a mask on right away when they enter our doors,” Mehta said.

If they can get patients who may have the virus in masks as they enter, then health care workers can proceed to screen the patient with a series of questions, and isolate them if necessary.

“If there’s anything concerning, then we isolate the patient so we take them away from the general waiting area and put them in an area which is safe for us to continue asking questions and giving medical care without exposing anybody else,” Mehta said.