Georgia town’s activism challenges South’s racial narrative

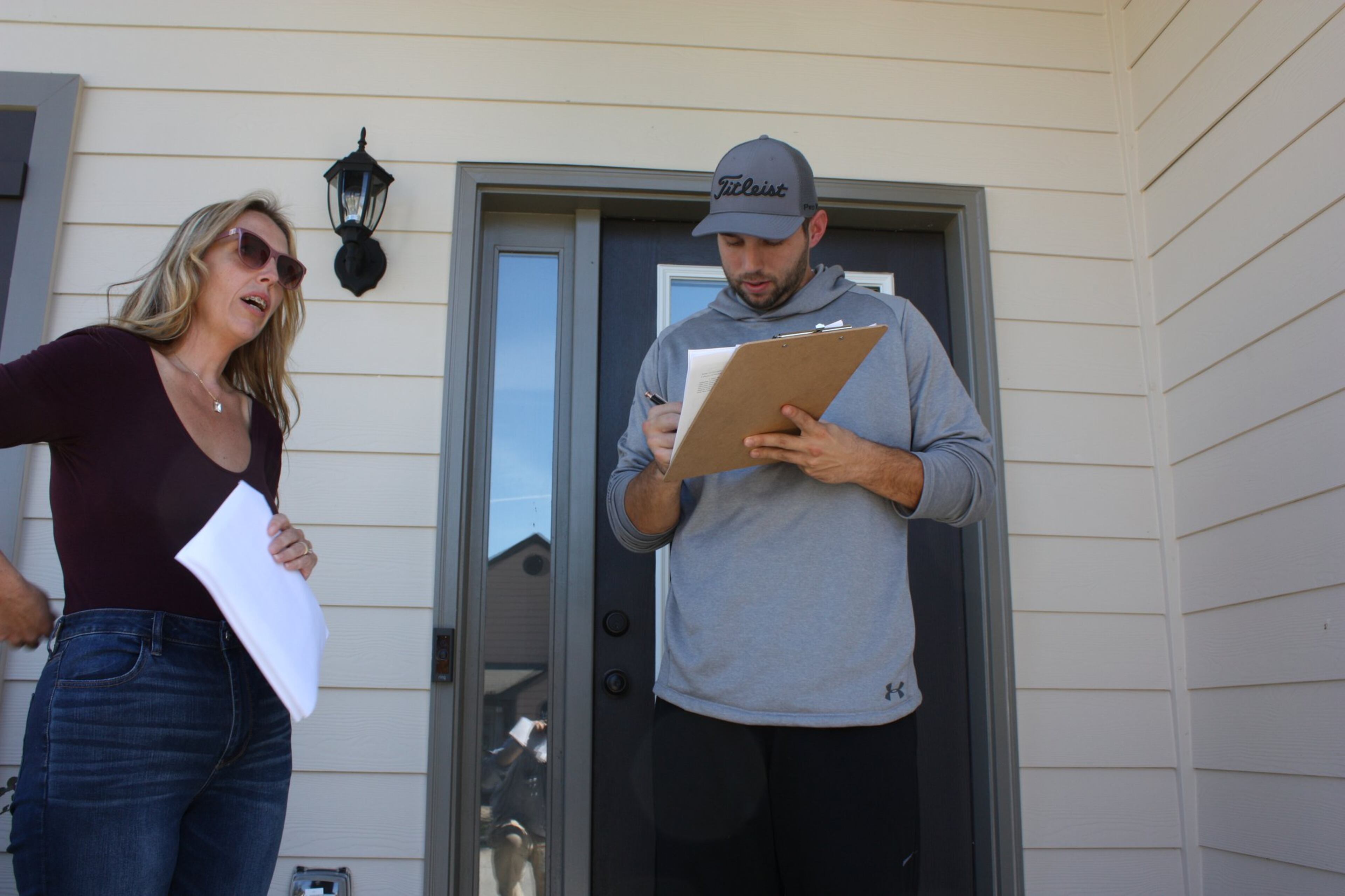

On a cool November afternoon in Hoschton’s Brook Glen neighborhood, resident Michael Jackson answered the door with a wary glance at the two people clutching worn sheets of paper. But he smiled when he recognized one as a neighbor.

“We’re with the recall committee,” Kelly Winebarger said.

Jackson needed no further preamble. He grabbed a pen and added his name to a growing list of residents in favor of recalling three-term Mayor Theresa Kenerly and Councilman Jim Cleveland.

“This is an upcoming city. Negative publicity is not something needed or wanted around here,” Jackson explained. “I’ve got two young kids, 7 and 4.”

The political struggle in tiny Hoschton, a city of fewer than 2,000 just northeast of Gwinnett County, is entering a new phase. Last Tuesday’s city elections changed the balance on the City Council and the move to force Kenerly and Cleveland from office is maturing despite long odds.

“This is high stakes,” said Erma Denney, a former Hoschton mayor who now serves on the Jackson County Board of Election. “This is the integrity of a community, and it will keep it divided until it is remedied.”

Six months ago, Hoschton became a national reminder of the South's legacy of bigotry and segregation following an Atlanta Journal-Constitution investigation into claims that Kenerly sidetracked a black candidate for the city administrator because of his race, telling council members the mostly white city wasn't "ready for this."

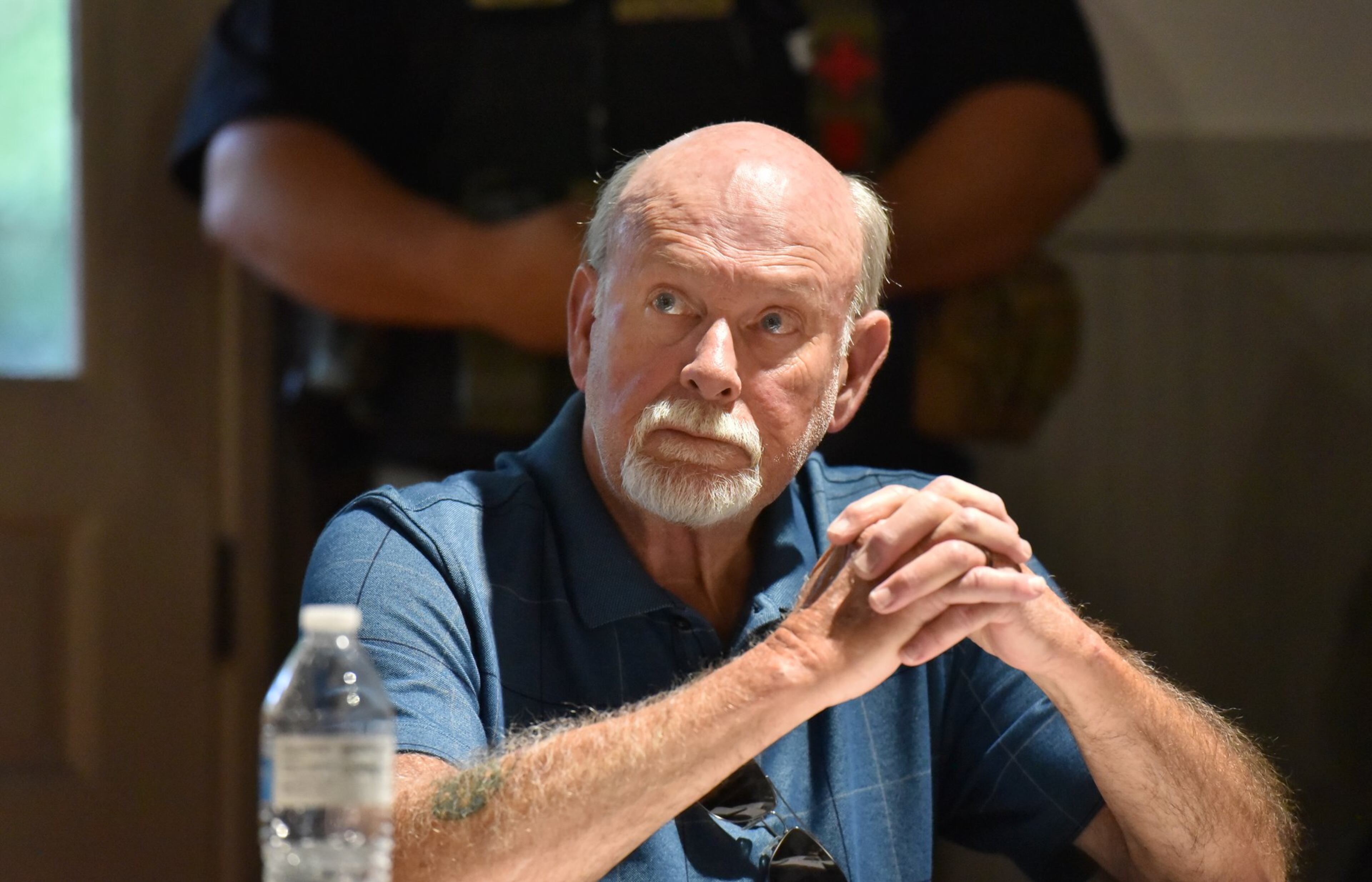

Cleveland, a political ally of the mayor, came to her defense, backing the sentiment while saying her tearful apology the following week was “very sincere.”

“I understood where she was coming from,” he said. “I understand Theresa saying that, simply because we’re not Atlanta. Things are different here than they are 50 miles down the road.”

Cleveland then poured gasoline on the fire by volunteering his belief that interracial marriage wasn’t “Christian” and that seeing interracial couples of television “makes my blood boil.”

Neither Cleveland nor Kenerly responded to calls and emails soliciting comment for this story.

Newspapers and wire services across the nation picked up the thread and Hoschton, for some, became that week's example of America's racial divide. As one Twitter user wrote, "Where's Sherman when you need him?"

But what’s happened since has upended stereotypes and awakened a political movement.

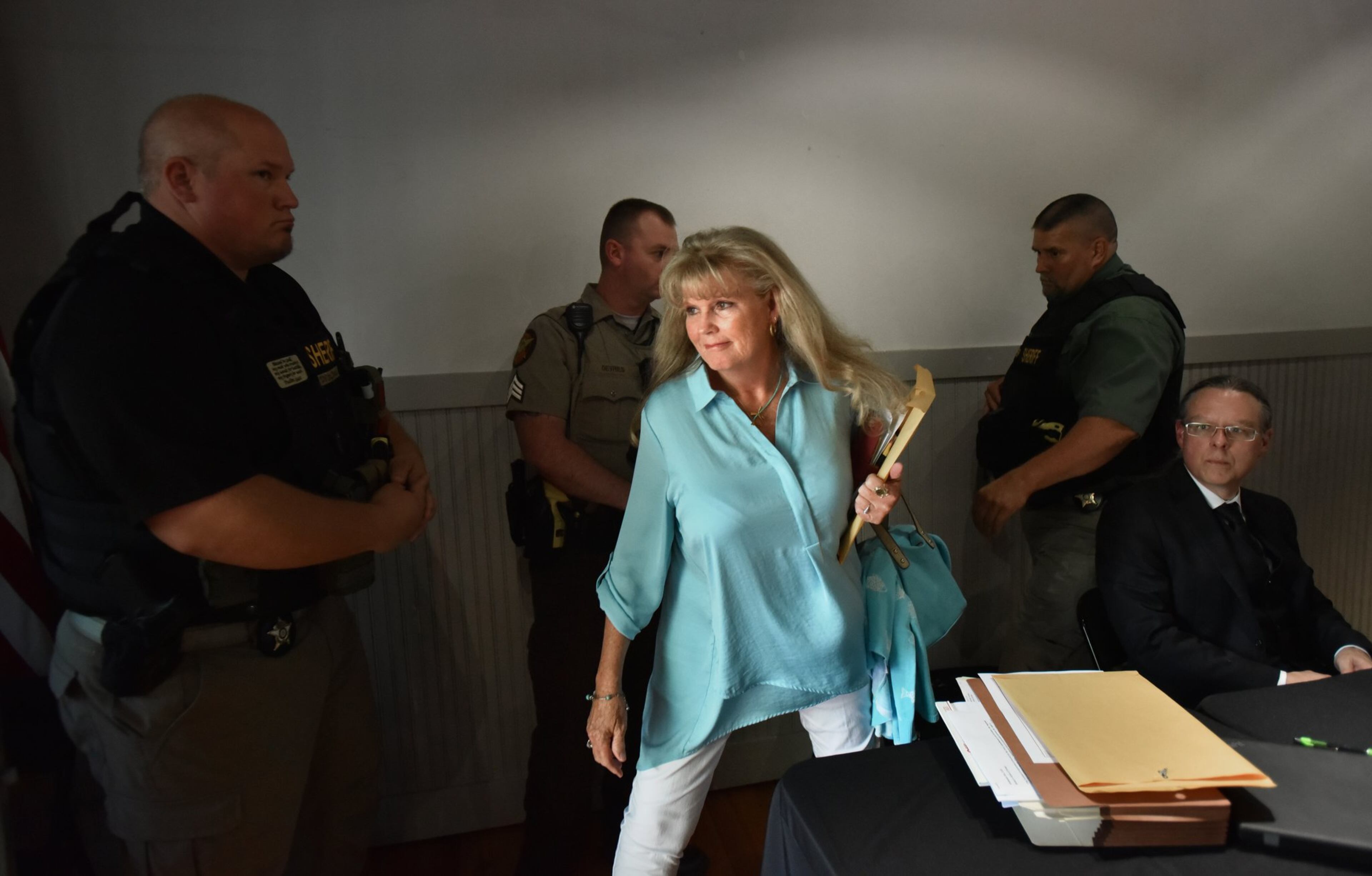

In this small town in the Deep South where nine of 10 people are white, dozens of residents lined up to file ethics complaints against their white mayor and a long-serving white councilman because of their bigoted statements about black people. In a show of solidarity, the heads of the Jackson County Democratic and Republican parties sat side by side to receive them.

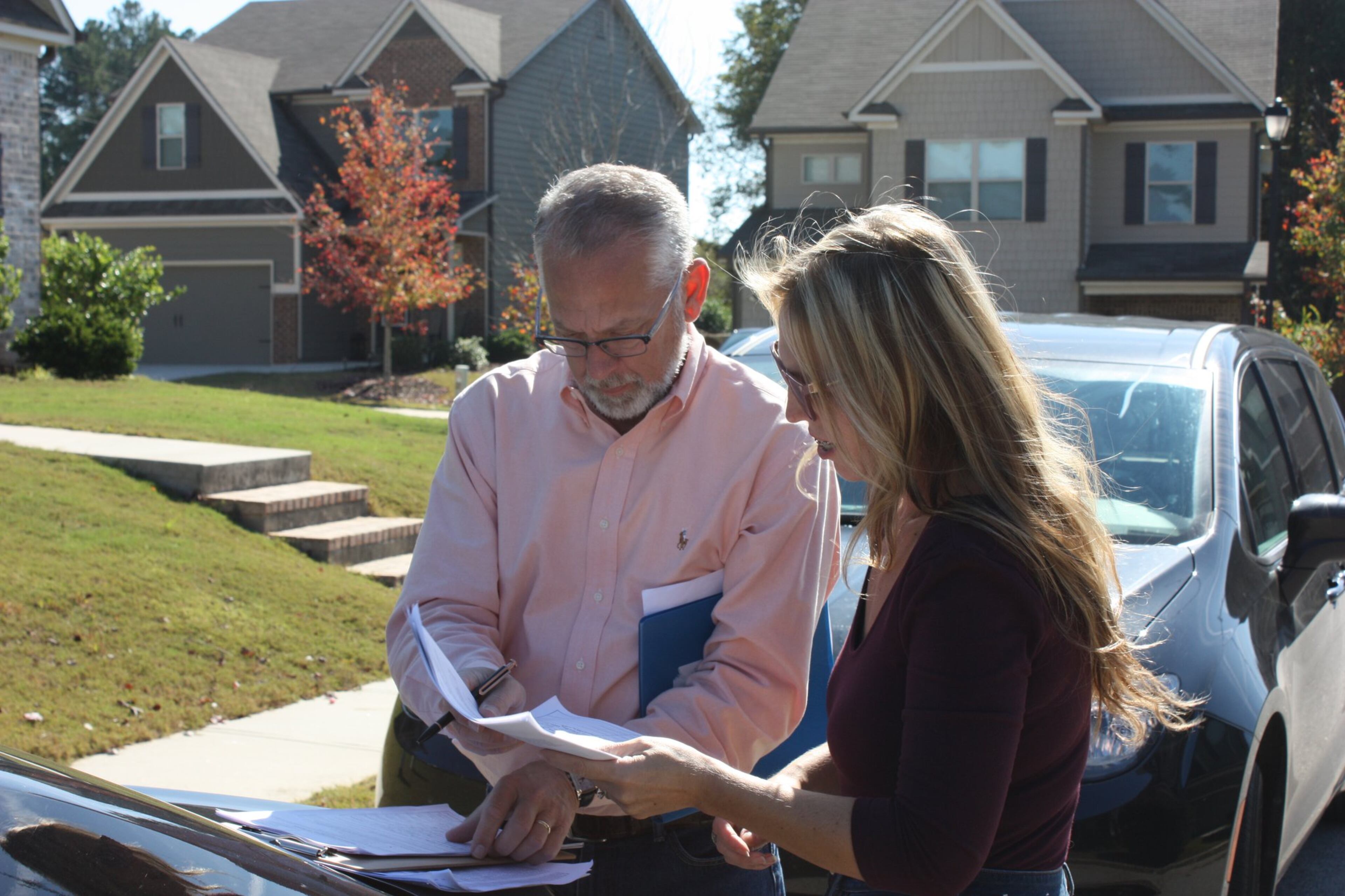

That campaign failed because the council had long ago neglected to appoint an ethics commission. So residents instead reorganized as a recall committee to force Kenerly and Cleveland out of office. Some, like residents Adam Ledbetter and Shantwon Astin, saw in the controversy a political awakening and filed to run for City Council.

‘Giving citizens their voice back’

Last weekend, Ledbetter and Astin chatted with local voters at a candidate “meet and greet” days before the election. The two men — one white, one black — barely knew each other before the controversy. But they bonded and campaigned as a team, pledging to restore Hoschton’s good name.

Hoschton is growing fast as metro residents push farther out in search of quiet, affordable neighborhoods. Ledbetter said he is amazed how many voters have just moved to town and aren’t aware of the Cleveland’s comments or the alleged discriminatory actions of Kenerly.

“They have no clue,” he said. “Then they Google Hoschton and they are like, ‘Whoa!’”

Astin, who is black, talked to voters about restoring trust in government and representing their voice in City Hall.

“We don’t have a voice — yet,” he told a small group of white voters. “This is about giving citizens their voice back.”

He didn’t dwell on race, except to say he never has experienced racism from his neighbors.

“Everybody is ready to move on and get the business of the city done,” he said.

The Hoschton that made national headlines in May isn’t the city Astin said he knows.

“A lot of people are ashamed of the reputation of the city,” he said. “I have lived here three years and I’ve never had an issue with race. Not one.”

Campaigning with Ledbetter was a risky strategy for both. Hoschton doesn’t have wards or districts, so all council candidates run citywide with seats going to the top vote getters. As voters went to the polls Tuesday, there were two seats available, and one of them is held by incumbent Mindi Kiewert, who has been silent on the controversy but is viewed as an ally of the mayor.

“We can’t change Hoschton unless we get her seat,” Ledbetter said.

The gamble worked, and worked in a big way for small-town politics. Both Astin and Ledbetter won with nearly identical vote totals, defeating the incumbent by a two-to-one margin.

The campaign to recall Kenerly and Cleveland is the biggest political story in the city, but rather than hindering their campaigns, both Ledbetter and Astin said it actually was a boon. Residents who were disengaged from local politics are paying attention now, Astin said.

Recall hurdle high

With that election behind them, Hoschton residents turned their attention back to the recall, which is an even more improbable political solution.

Georgia has a complicated, multi-stage process for recalling an elected official, requiring two separate petition drives before an election can be called.

But if the Hoschton recall committee succeeds, it won’t be a first.

In 2015, voters in Meigs, a small town in southwest Georgia, successfully removed their mayor, a troublesome figure who had been arrested multiple times while in office and prompted numerous lawsuits from city employees alleging hostile work environments.

Most efforts, however, never make it to a vote.

Earlier this year, some Chattooga County residents attempted to recall school board chairman John Agnew over a decision by the board to revert from a four-day school week to a traditional five-day week. A judge tossed out the petition in May, ruling it was based on a false charge.

Kenerly and Cleveland tried the same approach in Jackson County Superior Court last month, but Judge David Sweat approved the recall committee's initial work, allowing the effort to go ahead.

For the second stage, committee members needed to collect signatures of at least 30% of voters who were registered during the last election to trigger a citywide vote to determine whether Kenerly and Cleveland would be cast out. Organizers say they exceeded that threshold last week, but have continued to collect signatures.

For Cleveland, that means a recall election is a near certainty. For Kenerly, maybe not. The mayor has appealed the Superior Court decision upholding the grounds for appeal to the Georgia Supreme Court.

In a brief filed with the court, Kenerly’s lawyers claim the first allegation in the petition, involving the mayor’s alleged comments about a black job candidate, are a “reprehensible mischaracterization” and that her words were “misconstrued … as indicative of personal racism.” In other words, Kenerly’s alleged assertion that Hoschton wasn’t ready for a black administrator was not a reflection of her personal beliefs.

The Supreme Court has 30 days to decide whether to take up the case. That raises the possibility that county elections officials could order two separate recall elections, beginning with Cleveland.

If the court rules in Kenerly’s favor, she will be allowed to complete her term. Ledbetter, now a councilman-elect, said he has heard from enough voters to know they are ready to move on.

“They want the reputation of our town restored,” he said.