As Georgia fights coronavirus, Kathleen Toomey catches spotlight

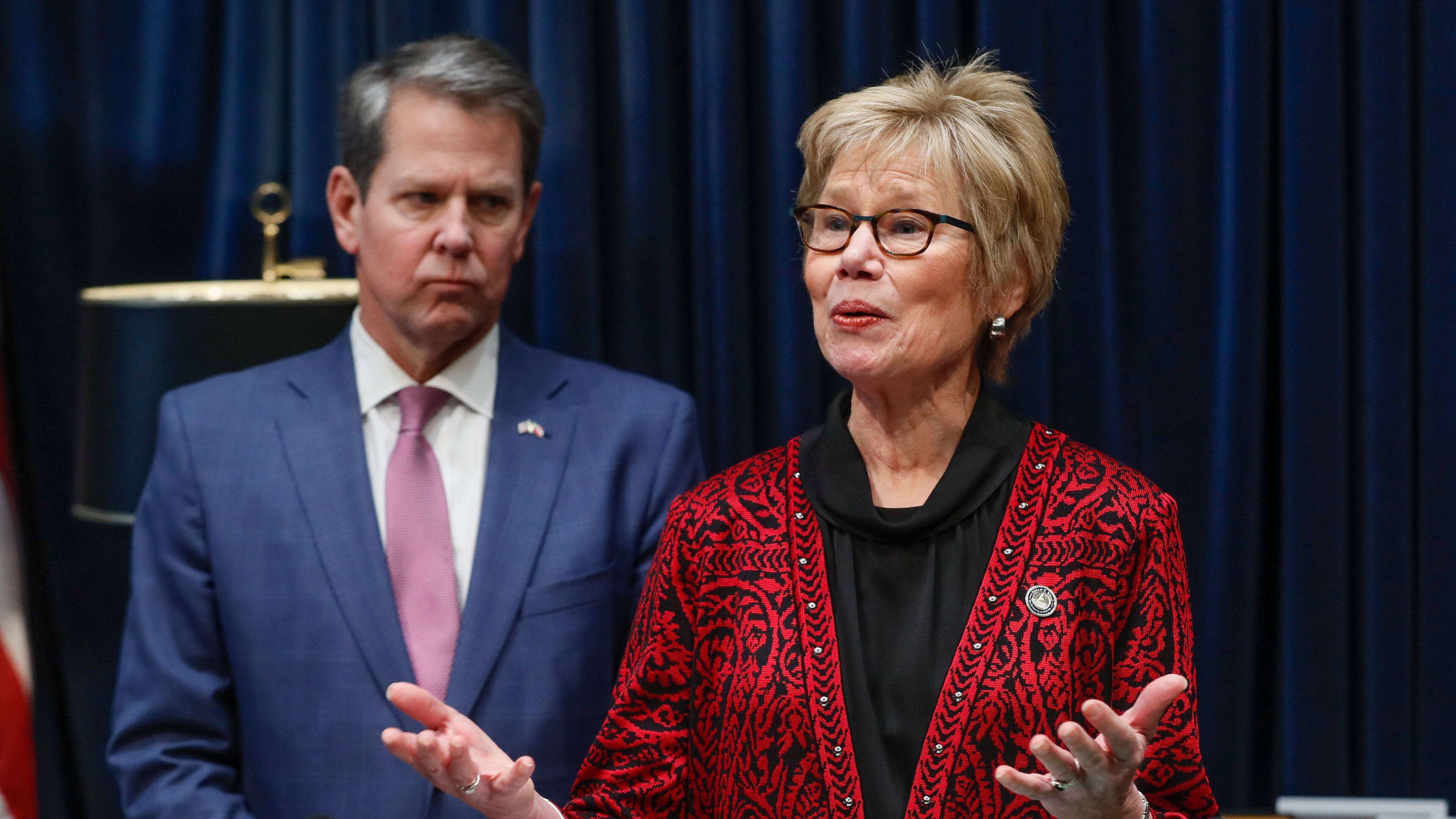

Gov. Brian Kemp long resisted issuing a statewide shelter-in-place order. When he finally did at a press conference last week, he said it was based in no small part on the counsel of the woman standing somberly a few feet away: Public Health Commissioner Kathleen Toomey.

Dr. Toomey has stood behind and beside but rarely in front of her boss as Kemp’s critics accused him of moving too slowly to combat the coronavirus pandemic. She is one of the state’s most visible leaders during the growing emergency, even as the governor’s office often has kept a tight grip on health officials commenting publicly.

Georgia’s chief medical officer has delivered dire messages about the state’s limited coronavirus testing and the scientific imperative for social distancing – sometimes in more urgent terms than those used by Kemp. But unlike Anthony Fauci, the nation’s top infectious disease expert who’s occasionally corrected or disagreed with President Donald Trump in media appearances, Toomey has been careful not to contradict Kemp.

Her responsibilities are huge. She oversees testing and efforts to secure ventilators and other emergency equipment. The roughly 5,600-person Department of Public Health she heads is the clearinghouse for coordination between state agencies, health care providers and medical facilities, and it was recently granted power to close any business that doesn’t comply with Kemp’s shelter-in-place order.

History will ultimately determine how effectively the state protected Georgians during this fast-moving crisis. But Toomey, serving her second stint as Georgia’s top public health official, so far has received high praise for her work, even among some Democrats and public health officials who have been unsparing in their criticism of Kemp.

“I am certainly a big fan of Dr. Toomey,” said state Rep. Pat Gardner, D-Atlanta. “We are very lucky to have her.”

Toomey's four-decade career has taken her from an Inuit fishing village to Botswana, from the beginnings of the AIDS crisis in San Francisco to Atlanta, where she worked for the state, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Fulton County overhauling its health department.

The coronavirus, however, represents a career-defining challenge on an entirely different scale.

Toomey declined to be interviewed for this story, saying she did not want to be singled out in a team effort.

“This pandemic and the response is unprecedented,” Toomey wrote in an email to The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. “I don’t want to do anything that in any way will undermine the team spirit we have developed that will ensure our continued coordination and collaboration for a strong response.”

‘Very personal’

You could say the 68-year-old Toomey has long feared something like the coronavirus.

When she interviewed to join Kemp’s team, Toomey was asked about what kept her up at night. Without skipping a beat she responded, “the potential for a pandemic flu outbreak,” according to people familiar with the exchange.

Those who have worked with Toomey describe her as passionate, intelligent and down-to-business. In her media appearances – which have largely been managed by Kemp’s office – Toomey has stuck to the science and the numbers: what the state knows about the virus, how many tests have been processed and which groups of people are being prioritized to use them.

In recent weeks, though, Toomey has shown occasional flashes of how the fast-moving coronavirus has affected her personally.

She indicated she was deeply troubled by the number of people who have described the virus as a hoax on social media in a March 27 interview with the AJC. And in a March appearance on Georgia Public Broadcasting, Toomey disclosed her grandfather died of Spanish flu during another globe-sweeping pandemic more than a century ago.

“This is very personal to me,” Toomey said on “Political Rewind.” “I’m in a position now where I can actually have the outcomes of this pandemic be different than what happened to my family.”

From Alaska to Atlanta

Toomey devoted much of her early career to another type of infectious disease: the sexually transmitted variety.

As a new doctor working in tiny Kotzebue, Alaska, in the early 1980s, Toomey discovered that more than 25% of the native population she was serving had chlamydia. Her work developing a screening program and treating patients roughly 1,000 miles away from the nearest major hospital inspired the 1990s television program “Northern Exposure.”

Toomey moved to Georgia in 1987 to join the CDC, and by the mid-1990s she was working as the state’s epidemiologist. It was in that position where she ended up in the middle of her first major public health crises.

In 1994, the state used its public health legal powers to quarantine two men who had drug-resistant tuberculosis. One was an AIDS patient named John Kappers, who died while appealing for his release. The state argued the men needed to be quarantined to receive enough treatment to make them noninfectious, but it prompted an outcry from the LGBTQ community and a lawsuit from the ACLU, which argued the patients’ civil liberties were being flouted.

Attorney Gerry Weber, who was legal director of the Georgia ACLU at the time, said he came away impressed from his interactions with Toomey as they successfully pushed for the legislature to overhaul the state’s tuberculosis control law.

“She was a dream to work with,” Weber said in a recent interview. “She was very thoughtful. She pushed back when she needed to but she listened and gave us insight about the medical issues.”

Three years later, Toomey was promoted to lead the agency that was the precursor to the Department of Public Health, or DPH. In that role, she expanded the agency beyond its traditional role of infectious diseases and services for the sick and helped prep the state for homeland security threats like anthrax in the aftermath of 9/11.

She took heat at the end of her tenure, in 2003, for signing off on a botched spot market purchase of 100,000 flu vaccines as the state’s supply rapidly depleted. Georgia was eventually able to recoup the $1.65 million it spent, but the state’s involvement in the convoluted scheme involving several companies in multiple states prompted an FBI investigation.

‘Toe that line’

Since Kemp lured her back to her old position in March 2019, Toomey has stayed in step with her boss.

Earlier this year, she defended the governor's proposal to trim funding from state health programs and insisted they wouldn't disrupt core services even as legislators of both parties pushed back.

Her efforts to thread the needle as a Kemp appointee and steadying scientific voice came into focus in March as the coronavirus put a halt to nearly all aspects of everyday life in Georgia.

During an early press briefing, Toomey didn't correct one of her deputies, state epidemiologist Cherie Drenzek, when she said that people who are "not showing symptoms of COVID-19 disease do not pose a risk," even though the CDC had issued guidance that "some spread might be possible before people show symptoms." Weeks later, as Kemp announced a statewide shelter-in-place order, he was ridiculed for seeming to suggest asymptomatic transmission had just been discovered.

As Kemp faced intensifying pressure to issue the order, Toomey repeatedly dodged questions about what courses of action Kemp should take.

“It is not simply a public health decision,” Toomey said when the AJC asked about a statewide shelter-in-place order five days before Kemp made the call. “There are also political implications I can’t possibly imagine and economic issues that I do not know about.”

After the governor ultimately announced the new restrictions on April 1, Toomey embraced them wholeheartedly.

“We feel the time is appropriate to take very aggressive community mitigation measures to address spread,” Toomey said.

Democrats, public health officials and others have kept Toomey separate from Kemp for not acting faster and DPH for not releasing more detailed statistics and limiting the hours for its coronavirus hotline.

“She’s doing as well as anyone can do. We’re dealing with a situation that’s changing every day,” José F. Cordero, head of the University of Georgia’s department of epidemiology and biostatistics, said of his former CDC colleague.

State Rep. Jasmine Clark, a Lilburn Democrat with a PhD in microbiology and molecular genetics, said public health officials may not be entirely free to speak because of politics.

“I still think behind-the-scenes there’s only so much that can be said without being accused of undermining those who are in power,” Clark said. “I do feel like (Toomey) has to kind of toe that line and be really careful about not appearing to undermine the governor’s decisions.”

Kemp's office has sought to remove any daylight between the governor and Toomey, especially after the governor's chief of staff suggested in late March that the threat of the coronavirus has been overstated.

Toomey “is the key advisor on all questions of public health for the state,” Kemp said in a statement to the AJC. “Commissioner Toomey’s expertise and wealth of experience is near un-matched across the country and Georgia is lucky to have her at the helm of DPH.”

Toomey said she’s “proud of the work we have done together across the state” and declined to comment on her work with Kemp beyond that.

Her defenders say that there’s no one better positioned to take on the crisis for Georgia.

“I know she’s doing a great job,” said Atlanta City Council Member Carla Smith, who worked with Toomey on the Fulton Board of Health. “At some point, people are going to start looking for people to point their finger at, but it won’t be her. She will have done everything.”

Staff writers Ariel Hart, Alan Judd, Greg Bluestein and Helena Oliviero contributed to this article.