Georgia colleges struggle with legacy of blackface, racist imagery

In the University of Georgia’s 1962 yearbook, the year after black students Charlayne Hunter-Gault and Hamilton Holmes integrated the school, the pair only appear in their standard class photos.

There is no mention of the court battles, protests, angry stares and a nighttime student riot that greeted Hunter-Gault and Holmes as they arrived on campus.

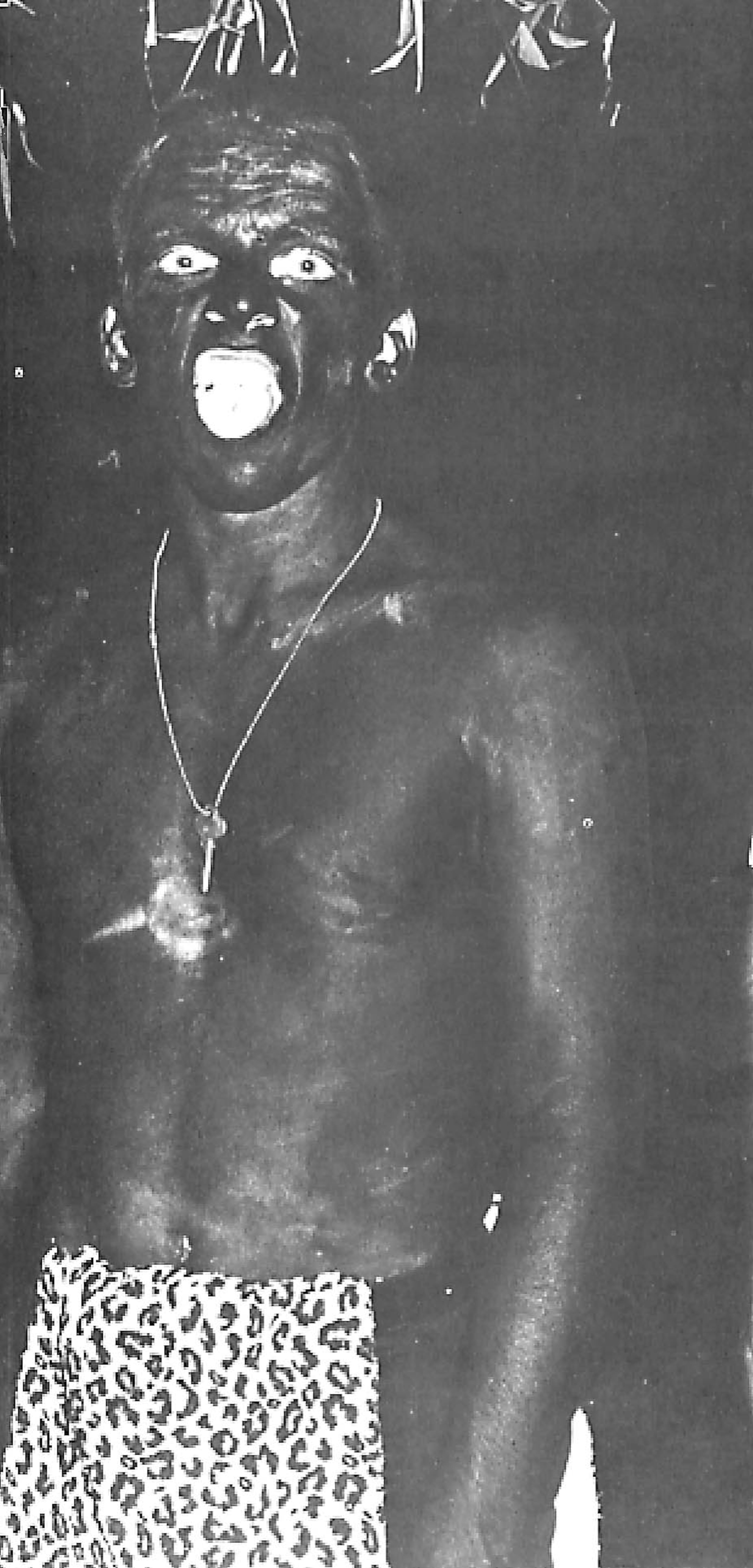

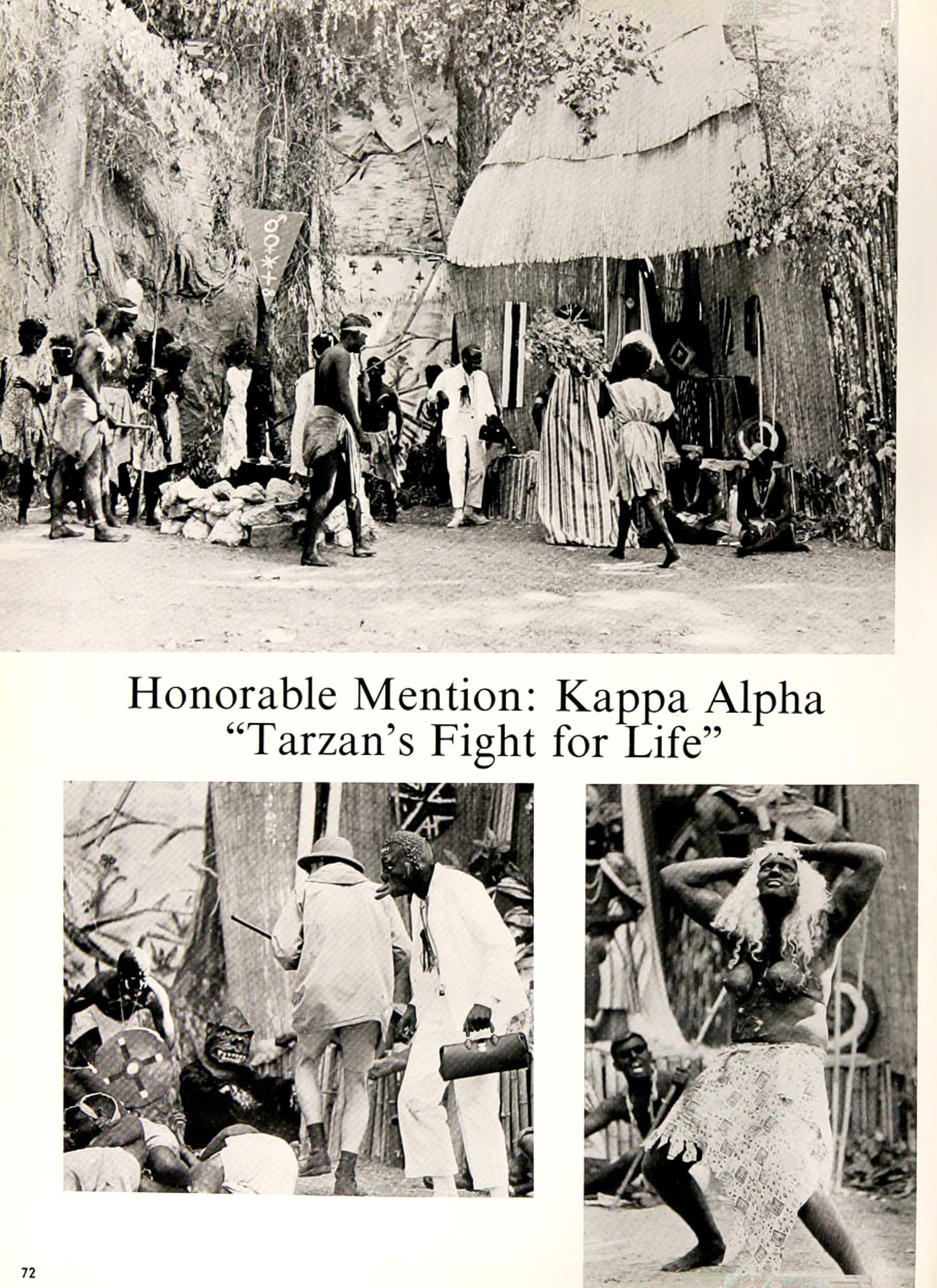

There were, however, at least two occasions where white students were featured in the book wearing blackface, a degrading satire of African-Americans that began in the early 19th century. On one page, two sorority girls laugh and pose as a black-faced couple. On another page, rows and rows of Kappa Kappa Gammas smile for their official sorority portraits, while a larger photo shows two of them dressed as black-faced pickaninnies, with one asking, “Lenda, who put the smile on the kool aid pitcher?”

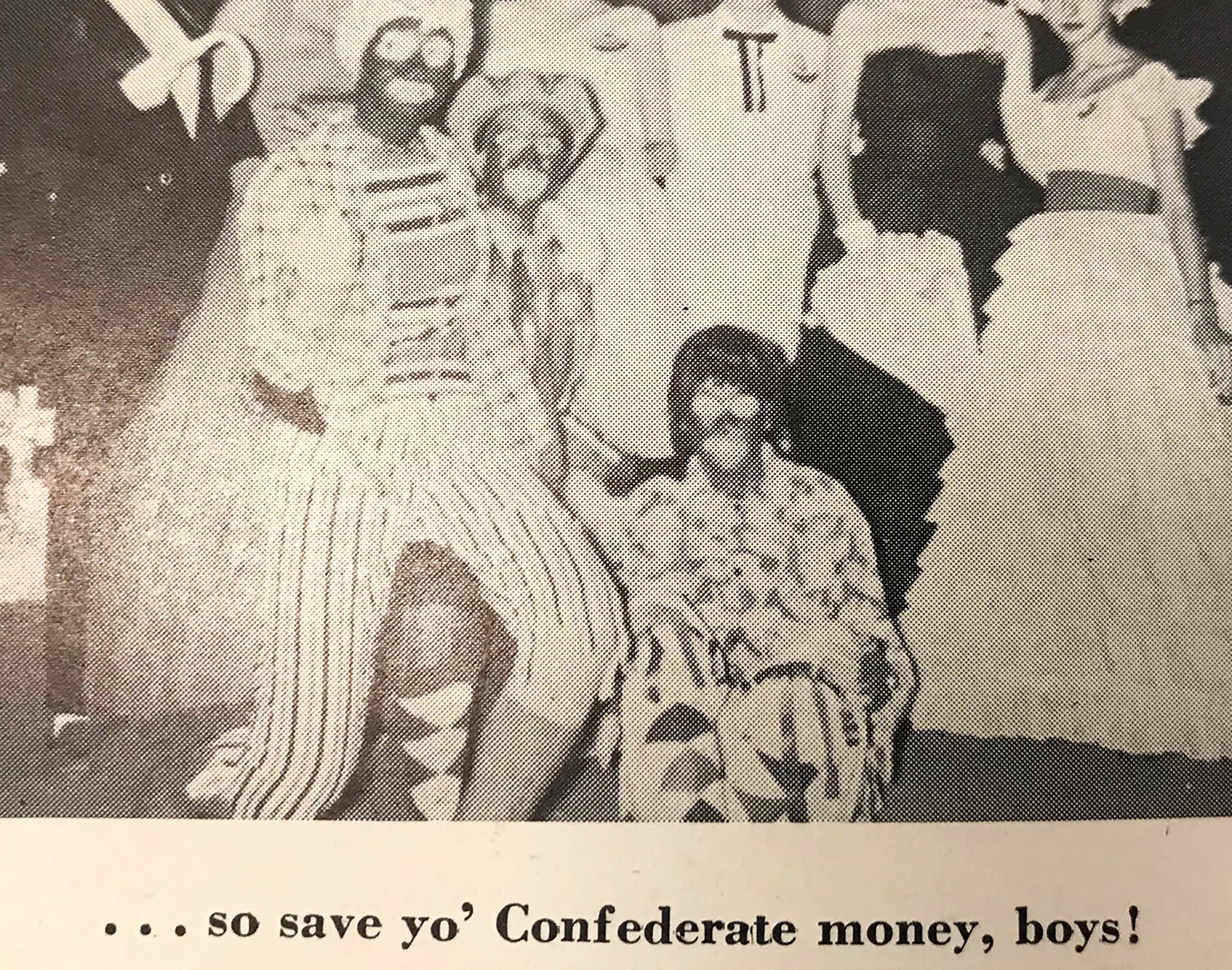

Such images seemed buried in history until Virginia was plunged into a political crisis this month when Gov. Ralph Northam and Attorney General Mark Herring were accused of wearing blackface during their college days. The trigger was a photo of students in blackface and a Ku Klux Klan hood in Northam’s 1984 medical school yearbook.

Similar photographs have been found in dozens of college yearbooks from recent decades. They highlight how even the country’s highest institutions of learning have struggled to move past a history of racism. While African-Americans have long viewed blackface as offensive, some white Americans still don’t understand why others say the images are problematic.

Here in Georgia, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution recently reviewed several decades of yearbooks of some of the state’s largest colleges and universities. It found more than two dozen images of typically unnamed students in blackface at UGA, Emory, Georgia Tech, Georgia Southern, Georgia State and Mercer universities.

Most of the photos were in the 1950s and 60s, during the height of the Civil Rights Movement, and were typically confined to fraternities and sororities. As such images receded from yearbooks, incidents of blackface continued to roil campuses in Georgia as recently as 2004.

The attention has forced a renewed reckoning, at a time when many colleges are already answering how they profited from slavery or have buildings or memorials named after Confederate leaders. Emory President Claire E. Sterk announced last week she plans to create a commission to review racist images in yearbooks and other publications.

Conversations about the past

Blackface dates back to the 1830s, when traveling white entertainers darkened their skin with polish or burnt cork to mock slaves and free blacks.

White minstrel performers distorted the features and mannerisms of blacks to portray them as lazy, stupid, irresponsible, superstitious, hypersexual and inarticulate cowards. They wore old clothes, exaggerated their movements and adopted a stereotypical black vernacular. Often, they would paint the mouth and area around it with red or white polish to give the appearance of big lips.

» Read more about the history of blackface and its early 19th century roots

“By distorting the features and culture of African Americans — including their looks, language, dance, deportment and character — white Americans were able to codify whiteness across class and geopolitical lines as its antithesis,” according to an essay on the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture’s website.

Fredrick Harris, an African-American from Atlanta who earned his undergraduate degree from UGA in 1985, was unaware of the yearbook photos. He recalls several other situations on campus he considered offensive such as the annual “Old South” celebration where some white students wore Confederate uniforms or students who sang “Dixie” at football games.

"It's important to have the conversation so we no longer have these conversations," said Harris, who teaches political science at Columbia University and was part of protests at UGA to increase racial diversity among faculty. "To get beyond the racial fissures in society, we have to have conversations about the past."

Even today, not everyone is convinced theses images are offensive.

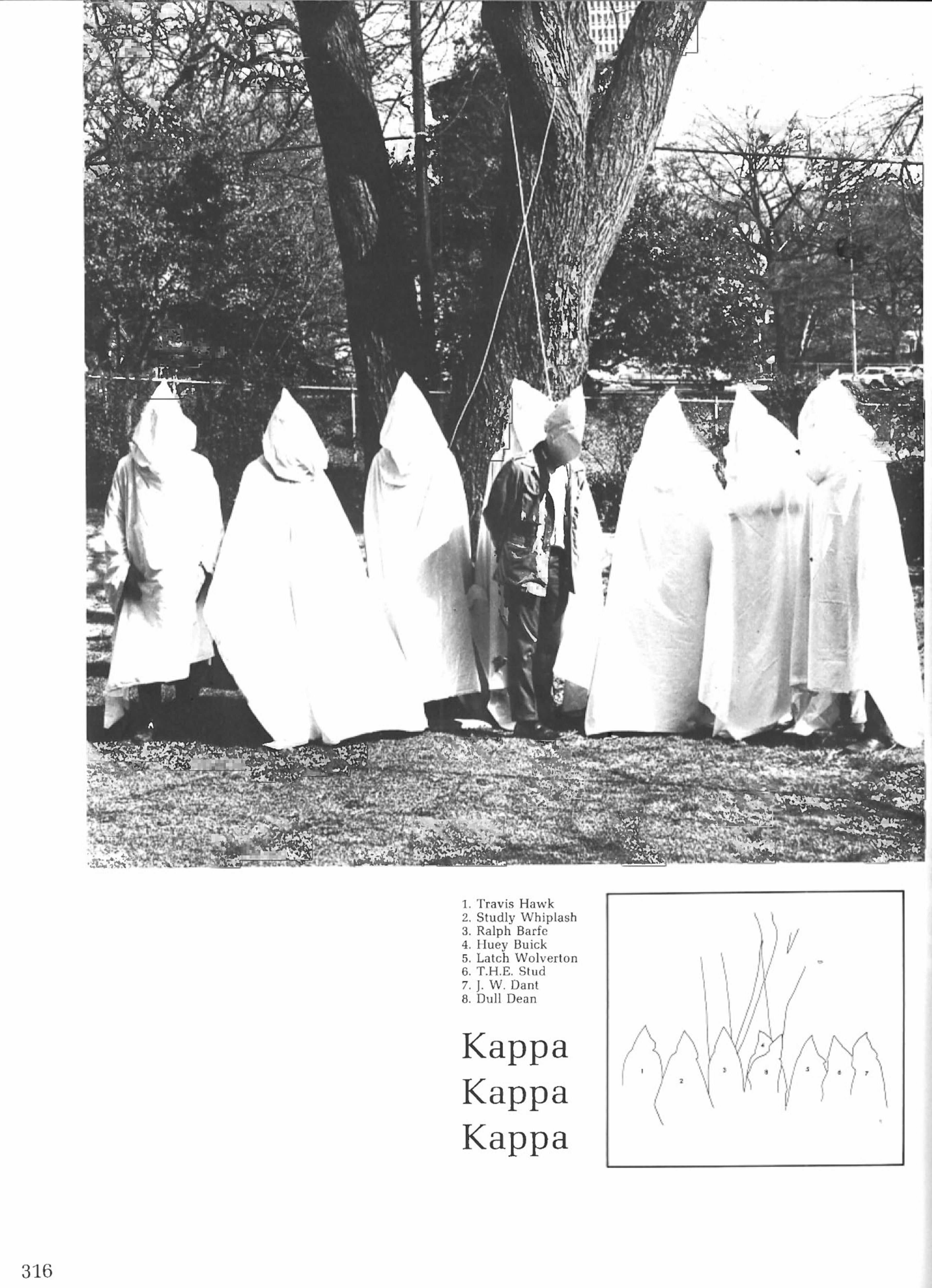

Russell Rheams was a junior at Georgia Tech and one of the yearbook editors in 1968. That year’s yearbook included a photo of seven people wearing white Ku Klux Klan robes and hoods gathered at the foot of a large tree in broad daylight. In the middle of them stands a man in plain street clothes with his hands behind his back, a cloth bag over his head and a noose around his neck.

Rheams, 72, who now lives in Sacramento, Calif., said he was not involved in including it in the yearbook.

“For the time, it was meant to be in good humor,” Rheams said. “Nobody meant anything bad by it. It was just another way of being funny, a bunch of kids being irreverent.”

He said he doesn’t condone the mock lynching that is depicted in the photo, and that “by today’s standards it’s rough, but you can’t judge the past by today.”

What would Rheams, who is white, say to people who are offended by the photo today and what it symbolizes? “Chill out,” he said.

Something done indifferently

The largest number of blackface photos found by the AJC were at the University of Georgia, the first state-chartered university in America. UGA has had a complicated history on race matters. While the university this month celebrated Hunter-Gault and Holmes in its "Georgia Groundbreakers" series, it's been criticized in recent months for its handling of a slave burial site on campus.

UGA has slowly increased its enrollment of African-American students to eight percent, but it is still less than several similarly-sized public universities in Georgia, such as Georgia State (41 percent) and Kennesaw State (22 percent).

Some blackface photos found in UGA yearbooks had racially-charged captions.

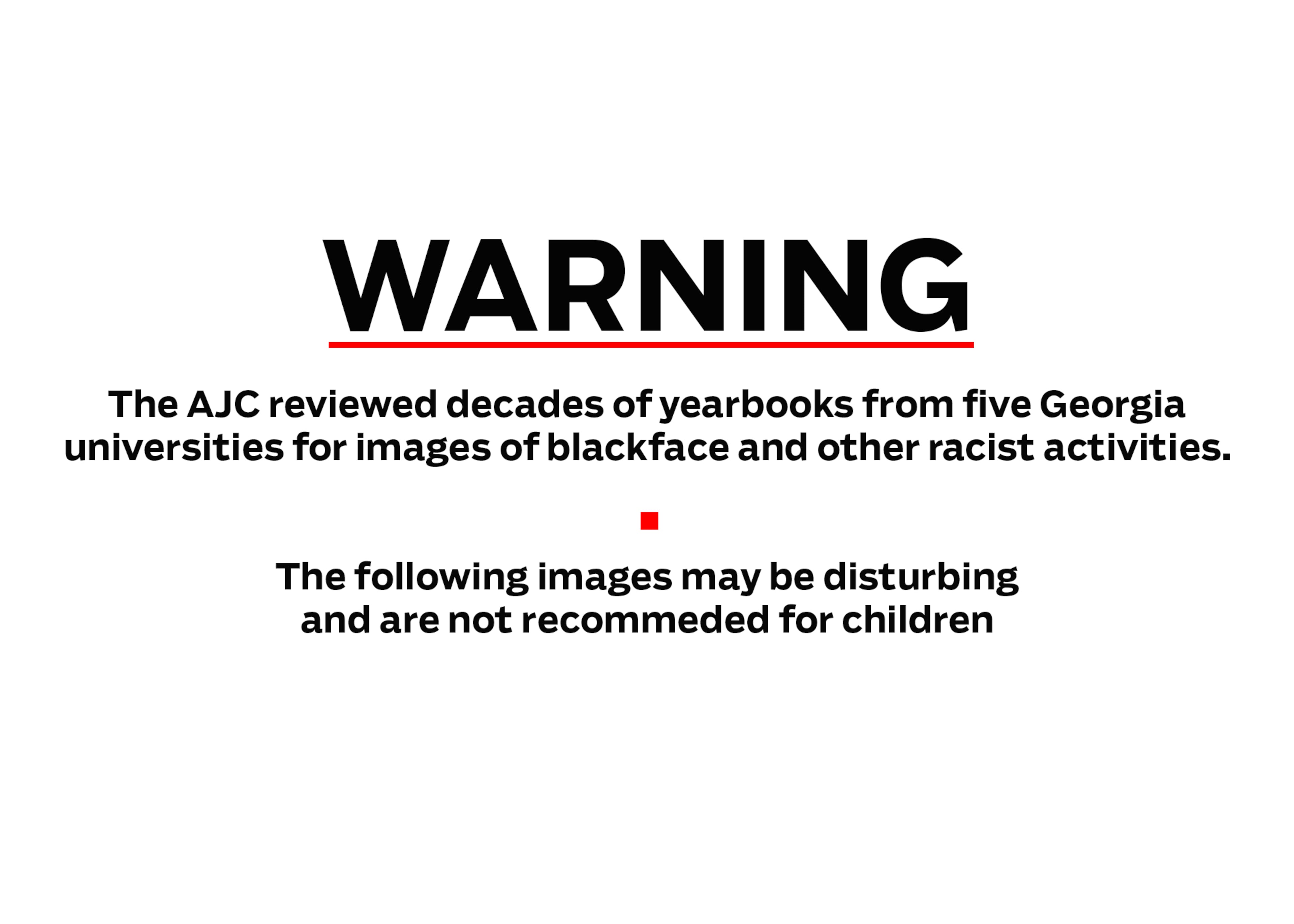

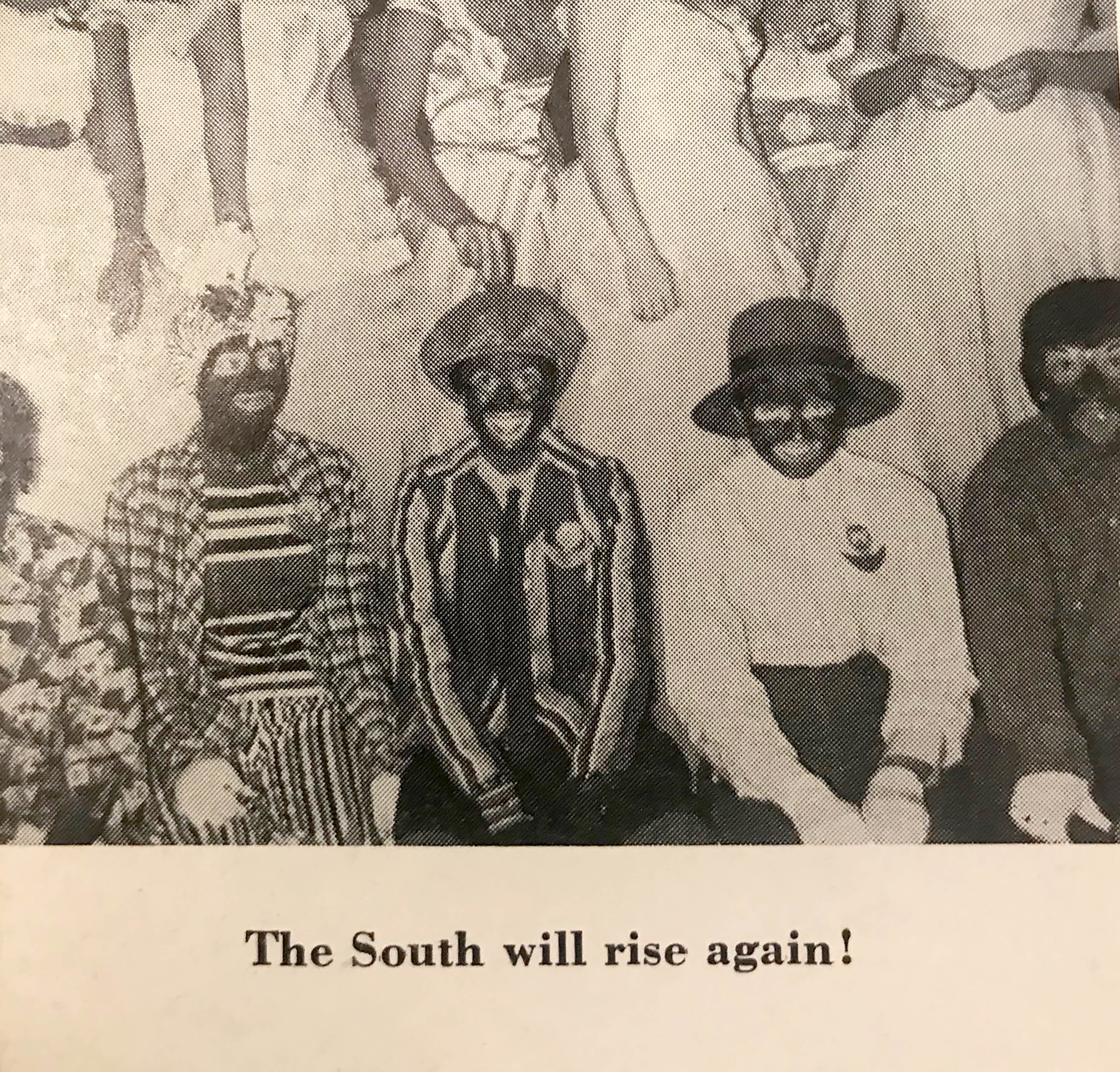

“The South will rise again,” read one caption of a 1958 yearbook photo of several women dressed in gowns with four people seated in front of them in blackface. On the next page were students in blackface with the caption “…so save yo’ Confederate money, boys!”

Many of the students in the fraternities and sororities at the height of blackface were well-to-do and later became well-connected, said retired UGA history professor Jim Cobb, who is white. For some white students, Cobb said, their only interaction with African-Americans were with those who were custodians or servants.

“It was one of those things that was historically trendy or rebellious to ‘go black’ and adopt black hipster lingo and people took it very lightly about what social implications it may have,” said Cobb, who attended UGA from 1965 to 1969 and called the images awful. “It was something done indifferently without any thought put into it.”

Cobb could not recall any protests of blackface. White students who would have spoken out would have been ostracized, Cobb believes. Black students were still in small numbers and already faced blatant racism, he said. Fighting a battle about blackface would have been difficult, he said.

Mercer yearbooks during those years included several blackface photos at such gatherings, including 1964, the year a young Nathan Deal was its student government association president. Asked if he was aware of the photos or gatherings where classmates were in blackface, Deal, the former two-term governor, said last week through Chris Riley, his business partner and former chief-of-staff, “absolutely not.”

Blackface increasingly became socially intolerable. African-Americans, in the wake of the Black Power Movement, which began in the latter part of the 1960s, became more vocal about campus discrimination. History books were being rewritten. Slavery, once written about as benign, was described as unconscionable.

The images largely disappeared from yearbooks in Georgia after the 1960s, but occasionally surfaced. A 1981 UGA yearbook includes an image of what appears to be a costume party in which four members of Alpha Delta Pi sorority are wearing blackface.

It remained a part of campus life outside the yearbooks. In 1992, a Georgia State University fraternity displayed a picture of members in blackface and wearing Afro wigs. In 1997, members of a University of West Georgia fraternity performed a Jackson 5 skit wearing blackface. Both universities this week condemned such acts.

Mark Anthony Thomas became the first black editor of UGA’s Red & Black newspaper in 2000. His appointment was heralded as a sign of Southern progress and attracted national media coverage. During his four years on the paper, he doesn’t remember ever publishing images of blackface. But he said the paper did publish Southern heritage images leading to internal debates.

“There was a celebration of the old South and Confederate culture that we had to accept,” said Thomas, now an economic development official for New York City. “At the same time, black students built their own culture and community and both Athens and the university supported us.”

There were still occasional eruptions. In one highly-publicized incident in 2004, two Georgia State fraternity members showed up with their faces painted black at a hip-hop theme party. A black student group retaliated with a flier using the fraternity’s name, Pi Kappa Alpha, on a picture depicting a Ku Klux Klansman and a man in blackface with a noose around his neck.

The reckoning continues

Two years ago, Wesleyan women’s college in Macon apologized for Ku Klux Klan rituals that were a part of student life in the early 20th century and continued for generations.

UGA said in a written statement that all yearbook content has been reviewed by Student Affairs staff prior to publication for at least a decade, and all student organizations are on notice such behavior is not tolerated. The renewed debated over blackface has prompted “many discussions in Mercer classrooms and other settings,” said university spokesman Kyle Sears. In a statement, officials at Georgia Tech and Georgia Southern condemned the images.

» RELATED | Emory University to create commission to review racist yearbook photos

Emory’s president, who took office in September 2016, said in an email to students and employees she will update the campus on plans for a commission that will review how the university “depicted images in our community” through yearbooks and other publications. The yearbooks are on an Emory website. For now, the university has no plans to remove them.

“The offensive and racist images in our yearbooks cannot be erased any more than they can be forgotten. They are a permanent part of our record,” Sterk wrote. “It is my fervent hope that they will serve as an indelible reminder to all current and future Emory students, faculty, and staff of the type of ignorance and hate we must passionately oppose.”

HOW WE GOT THE STORY

After admissions by Virginia's governor and attorney general that they appeared in blackface while in college, a team of Atlanta Journal-Constitution reporters and editors reviewed several thousand pages of yearbooks, spanning decades, from some of Georgia's oldest and largest colleges and universities. The newspaper found more than two dozen blackface photos. The AJC reached out to each school and others for comment about the images.