Why the South is anything but solid for either Clinton or Trump

The South is hardly a political monolith that votes in neat lockstep. But this presidential election threatens to fracture the region unlike any other in decades, smashing what once was called the “solid South” into a purply stew.

Republicans are playing defense in territory once considered safe harbor for conservatives, and top GOP strategists openly talk of relying on the same strategy that helped a generation of Democrats win local races even as the region was turning red.

Florida and Virginia could give its bounty of electoral votes to the Democrats for the third straight presidential election, and Hillary Clinton’s campaign is honing in on North Carolina. Georgia and even South Carolina could be competitive this year, and demographic changes could transform Southern neighbors’ electorates in the next decade.

At the same time, conservatives are consolidating their strength in deep-red bastions such as Alabama and leveraging the powerful advantage the GOP retains in much of the region thanks to the way congressional districts are drawn. And some Republican leaders are testing new messages and innovative policies to brace for the demographic changes.

November’s election comes as the South asserts itself in new ways. The advent of the “SEC primary,” the March votes featuring mostly Southern states, helped shape the presidential contest. Clinton and Republican Donald Trump have since crisscrossed the region, with Trump recently adding stops in Mississippi and flood-ravaged Louisiana among visits to Southern states.

The attention has left voters in both camps more energized. And polarized.

“Oh, he’ll carry the South,” Melissa Moore Truell, an educator waiting for a meeting in her central Alabama town, said of Trump. “He wants to protect our borders, safeguard the Second Amendment, defend religion. He’s not a politician; he’s a businessman and he’s an American.”

But Barbara Lee, a retiree from Staunton, Va., said she can almost feel the South turning blue.

“I’m not worried — I see the change,” Lee said at a get-out-the-vote rally in Virginia. “I think (Clinton’s) going to pick up North Carolina, South Carolina and Florida because of the grass-roots movement.”

A stronghold no longer

The South was for decades a stronghold for Democrats, though a renegade ticket led by Strom Thurmond briefly splintered the region in 1948. By the mid-1960s, that began to change.

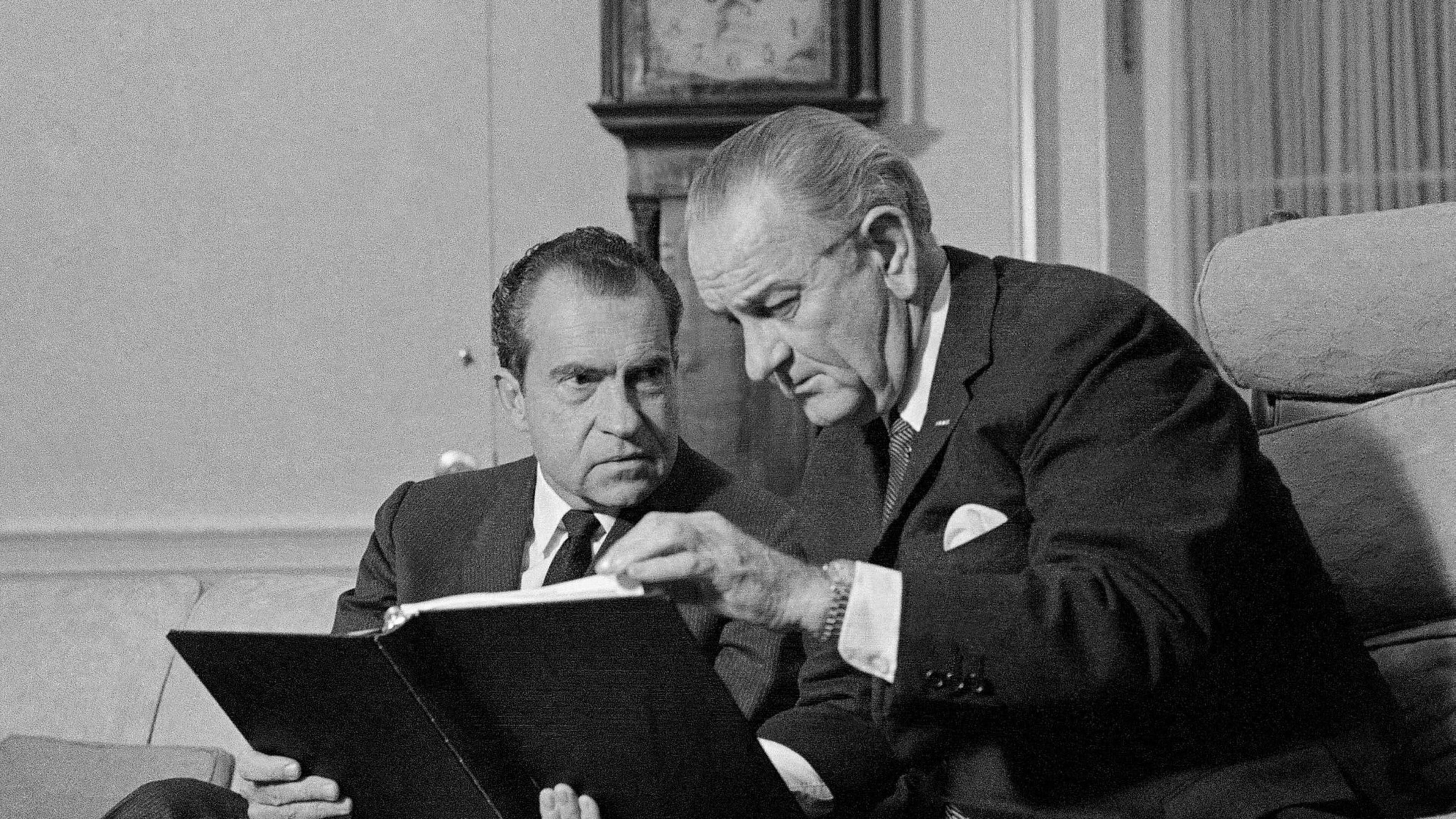

President Lyndon Johnson, after signing the 1964 Civil Rights Act, predicted that the Democratic Party had “lost the South for a generation.” That same year, conservative Barry Goldwater won only six states for the Republican Party, but five of them were in the South.

In 1968, George Wallace — who came to national prominence by declaring “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever” — took the Thurmond approach, winning Georgia, Alabama, Arkansas, Louisiana, Mississippi and one electoral vote from North Carolina as a third-party candidate.

Republican Richard Nixon, employing his “Southern strategy,” won every other state in the South that year except for Texas. The Republican Party, especially under Ronald Reagan, then transformed the region into a bulwark for the GOP.

Bill Clinton of Arkansas picked off Georgia and a few Southern states in his 1992 campaign, but the beachhead was short-lived. It was Barack Obama, though, who might have splintered the region for good. He won North Carolina, Virginia and Florida in 2008 and followed that up with a victory in the latter two states in 2012.

The Republican counterrevolt after Obama’s election, though, was devastating to Southern Democrats. The tea party movement breathed new life into conservatives, putting Democrats in swing districts across the region on the defensive.

By 2014, the GOP reclaimed U.S. Senate seats in Arkansas and Louisiana, and it ousted U.S. Rep. John Barrow of Augusta, the last white Democrat in the House of Representatives from the Deep South. But Democrats made gains, too, putting John Bel Edwards and Terry McAuliffe in the governor’s mansions in Louisiana and Virginia.

Democratic strategists are already looking to the next decade, when they hope growing numbers of black and Hispanic voters — who helped Obama win Southern states — could shape the votes in the South’s biggest states well into the next decade.

Democrats hope that Republicans and independents skeptical of Trump could hasten the changes. Libertarian Gary Johnson is polling double-digits in Georgia and some of its neighbors, and Trump’s divisive remarks and controversial policies could turn off college-educated white voters who helped fuel the GOP’s success.

Charlie Cook of the nonpartisan Cook Political Report recently silenced a room of some of Georgia’s most influential business leaders when he outlined the bad news that November will likely bring for Republicans. Given Clinton’s dismal favorability rating, he said, any Republican would likely have had a better shot at beating Clinton than Trump.

“In short, if Republicans nominated a potted plant, they’d probably win. Even with the structural advantages against the Republican Party that we have right now,” Cook said, adding that Ohio Gov. John Kasich or another “fairly innocuous” candidate “would have beaten Hillary Clinton like a rented mule.”

A campaign game of chicken

While Trump and Clinton joust over Florida and North Carolina — both states seem crucial to the Republicans’ election chances — complicated maneuvering is unfolding in some of the neighboring states. Talk of Clinton’s new investment and hires in Georgia led Trump’s running mate, Mike Pence, to make a recent two-day visit to the Peach State.

In an interview, Pence said he was certain that the campaign’s themes would resonate across Southern states, most of which Trump won by hefty margins in the party’s primaries.

“The message of a strong military, a strong America on the world stage, of revitalizing the American economy through less taxes, less regulation, more American energy, and smarter and tougher trade deals” reverberates in the South, Pence said. “It’s resonating across Georgia and across the country.”

Emory University political scientist Alan Abramowitz said it’s hard to decipher Trump’s unpredictable campaign strategy.

“But I suspect Trump will be spending his time in the traditional swing states as well and they will just hope that Georgia will end up in the GOP column as usual,” he said.

At the same time, though, more Southern Republicans are under pressure to distance themselves from Trump by using the very same blueprint their Democratic brethren used in decades past.

Veteran Republican pollster Whit Ayres said down-ticket GOP candidates could help preserve their elections by giving “no more than lip service” to Trump while focusing on local achievements in their districts.

It’s much like the strategy employed by U.S. Sen. Johnny Isakson, who has endorsed Trump but largely avoids his name on Georgia’s campaign trail.

Just as important to the GOP’s vitality in the South, Ayres said, was tapping into voter unrest while appealing to the growing number of minority voters the party needs to remain viable.

“The challenge from the Republican Party is to be able to accept that anger and frustration,” said Ayres, “and turn it into a productive direction.”

Staff writers Tamar Hallerman and Jim Galloway contributed to this article.

Shifting South

This is the first installment of a weekly series by The Atlanta Journal-Constitution on the political currents that define our region. Today’s story, by Greg Bluestein, probes the presidential race in Alabama ahead of the November election. Future pieces will look at Georgia’s other neighbors.

64 days until vote

Monday marks 64 days until Americans vote in federal and state races on Nov. 8. All year, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution has brought you the key moments in those races, and it will continue to cover the campaign’s main events, examine the issues and analyze candidates’ finance reports until the last ballot is counted. You can follow the developments on the AJC’s politics page at https://www.ajc.com/politics/ and in the Political Insider blog at https://www.ajc.com/politics/politics-blog/. You can also track our coverage on Twitter at https://twitter.com/GAPoliticsNews or Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/AJCGaPolitics.

Explore the series

Why Alabama is Trump’s red-state constant

Changing demographics drive Virginia’s purple reboot

In South Carolina, Democrats enjoy ever brief moment of parity

Florida, once again, could play lead role in deciding election