Distrustful of government and riven by differences, metro Atlanta voters on Tuesday rejected a $7.2 billion transportation plan that business leaders have called an essential bulwark against regional decline.

The defeat of the 10-year, 1 percent sales tax leaves the Atlanta region's traffic congestion problem with no visible remedy. It marks failure not only for the tax but for the first attempt ever to unify the 10-county region's disparate voters behind a plan of action.

"Let this send a message," said Debbie Dooley, a tea party leader who early on organized opposition to the T-SPLOST tax measure. "We the people, you have to earn our trust before asking for more money."

Kasim Reed, who fought years for the referendum as a legislator and as Atlanta mayor, rallied supporters gathered at a hotel in downtown Atlanta. "The voters have decided," Reed said. "But tomorrow I'm going to wake up and work just as hard to change their minds."

Gov. Nathan Deal's office told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution he would now take a central role in transportation planning for the state's metro areas, and he would not support a sequel to Tuesday's referendum.

"It's heartbreaking," said Ashley Robbins, president of Citizens for Progressive Transit, one of dozens of organizations that worked for the referendum. She predicted a loss of valuable young workers to the region's economy. "If Atlanta's not the region that we want, the young energetic people that drove these campaigns are going to leave."

Results were still pending Tuesday night in the state's other 11 regions. The Transportation Investment Act of 2010, which set up the referendum, was touted to raise as much as $19 billion if approved district by district.

Leaders with the Metro Atlanta Chamber, which pushed to create the referendum in the Legislature and then poured millions into a campaign to pass the tax, did not immediately return telephone calls.

Voter revolt

The metro Atlanta result was no surprise to independent pollsters who in recent weeks predicted an overwhelming loss, fueled by citizens' distrust of government and the metro area's splintered transportation desires.

Voters interviewed Tuesday — urban transit fans and suburban drivers — confirmed the predictions.

Shirley Tondee, a Brookhaven Republican, thinks the region must do something to solve constant transportation woes. But she voted against the T-SPLOST anyway. "I just don't trust that government is going to take the money and do what they say they're going to do," the retired sales representative said outside her precinct.

Robert Williams, a 59-year old electronic technician and a Decatur Democrat, is skeptical too. But in the end he voted yes.

"It was a struggle," he said. However, "we need to be able to grow. Traffic is one of the things that employers do take into consideration when they're thinking about where to bring jobs."

The metro Atlanta tax would have built a $6.14 billion list of 157 regional projects — relieving congestion at key Interstate highway chokepoints and opening 29 miles of new rail track to passengers, among others — as well as $1 billion worth of smaller local projects. The list was negotiated by 21 mayors and county commissioners from all 10 counties, and it contained about half transit and half roads.

The compromise didn't work.

Re-playing 40 years of Atlanta history, controversy built instantly around the proposed expansion of mass transit. Some loved it, some hated it.

Nevertheless, the campaign had set its sights on winning over conservative voters — at least, more of them than might usually say "yes."

Perhaps as a result, the campaign for the tax seemed at times unwilling to trumpet the transit in the list. Advertisements for the referendum showed many cars but little mass transit, until later on.

But that affected some transit supporters. Some metro Atlantans love transit, and some business interests favoring the tax said its expansion was key to drawing new jobs. But how much those voters understood the transit and other projects in the list was unclear.

DeKalb T-SPLOST opponents hit hard on the fact that south DeKalb did not get a new rail line in the list. The T-SPLOST would, however, give $225 million for commuter buses and stations in South DeKalb and $600 million for upgrades to the current MARTA system.

Gladys Pollard, a Decatur Democrat and attorney, mocked promises of the T-SPLOST. "'We're going to improve roads,'" she said. "What does that mean? It's so vague."

Pollard voted "no" because she believes south DeKalb should have gotten rail.

"They're not proposing anything that will benefit me," Pollard said. "We're not getting anything out of this. People in the north — they're going to benefit big-time."

Soft-pedaling the transit message didn't help the campaign with transit opponents, either, who called the transit a waste of $3 billion in a car-loving region. They came out early and in force, starting with tea party gatherings where the first organized opposition met.

Deeper insecurities were at play as well. A poll conducted by the Atlanta Journal-Constitution last year found that 42 percent of respondents believed new mass transit brings crime.

By election day, the issue was such a hot potato that a number of elected officials who voted for the T-SPLOST law or for the project list had stepped away or turned against it.

The campaign

Those may be challenges beyond any campaign's control.

But for all the money poured into it — more than $8 million for education and advocacy — the campaign had its own problems.

It drew some critics who found it top-down or obtuse, and it hit turbulence almost from its first moments.

Campaign tensions naturally grind as pressure rises. But by election night, transit advocates wouldn't watch election returns with the central campaign, but went to their own location at a Midtown Irish pub.

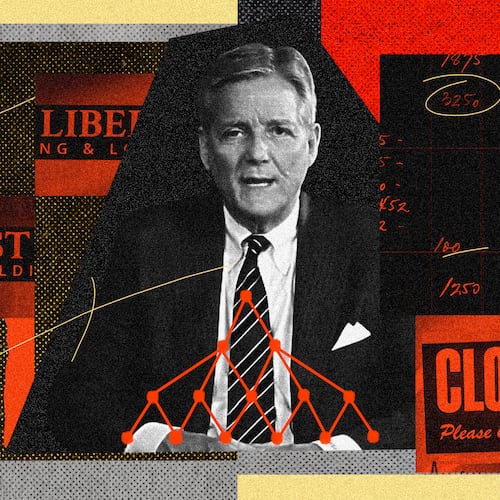

At the campaign's outset, its biggest hire was Glenn Totten, a Democratic strategist who once helped push the Georgia lottery to victory among referendum voters in this Bible-belt state. But within months, Totten, and then another Democrat, communications director Liz Flowers, left abruptly.

Those Democratic gaps in the Republican-Democrat team were eventually filled.

But when challenges arose within the T-SPLOST's Democratic, transit-fan base of voters, the campaign seemed to be caught flat-footed.

The campaign lost huge potential endorsements at the core of its voter base this spring, when the state organizations for both the Sierra Club and the NAACP came out against the tax, feeling there should be more transit in the list.

In each case, the decisionmaking boards of those groups spent weeks in debate over their positions, but were never contacted by the tax campaign, according to the heads of the groups.

Edward DuBose, president of the Georgia conference of the NAACP, said the NAACP even had a string of conference calls with speakers for and against, to help the group make its decision. They would have been glad to have a campaign representative speak, DuBose said, since the advocates the statewide group heard from didn't have a great deal of knowledge about the tax program. But he had no idea who the campaign manager was.

"I do find it odd" that they were never contacted by the campaign, DuBose said then. "Especially odd given that we are very visible."

Republican campaign supporters didn't run lock-step for it either. Although Gov. Deal helped the campaign, his first full-throated, passionate speech at a press conference urging its passage only came Monday, the day before the vote.

Deal said he had not had the opportunity to speak at large events for the Atlanta tax.

Now, with his predecessor's plan cashiered, the problem of funding a metro Atlanta traffic fix is his.

Staff writers Jim Galloway, Paige Cornwell, Greg Bluestein, Jeremiah McWilliams, Tammy Joyner, April Hunt and Wayne Washington contributed to this article.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured