A Chicago nonprofit the state paid to review charter school applications foot the bill for education agency employees to attend training sessions and conferences, even offering top staffers $1,000 stipends to take part in the events.

The nonprofit — the National Association of Charter School Authorizers — did not file mandated reports disclosing what it spent on employees of the State Charter Schools Commission of Georgia. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution found out by reviewing 4,500 pages of emails and documents.

Such vendor spending on state staffers may be prevalent.

Or maybe not.

It’s impossible to know because only about a dozen of the thousands of companies that do business with the state file vendor gift reports each year. Nobody is ever fined or prosecuted for not doing it.

Lobbyists must report regularly throughout the year on what they spend to influence lawmakers and state employees in Georgia. But vendors — the businesses that sell products to state government or do consulting work for agencies — are required to file once a year. And experts say they seldom do.

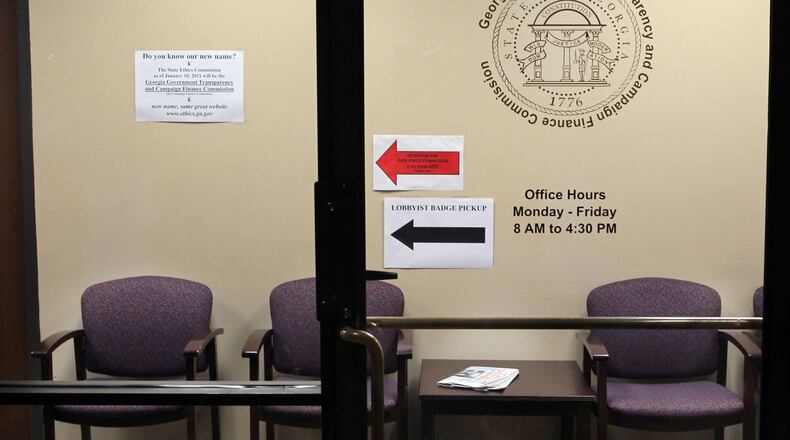

“There are no checks and balances in the system. There is no way to track it,” said Rick Thompson, a former executive secretary of the state ethics commission, where companies are suppose to file vendor gift reports. “We never tried to monitor it. If you wanted to file, you filed. There wasn’t anything we could do.”

Officials with the nonprofit charter school association said they didn’t know they were supposed to report what they spent on state employees.

“NACSA was not aware of Georgia’s vendor reporting requirements, and we appreciate the paper bringing this to our attention,” said Corrie Leech, the communications director for the association. “Moving forward, we’ll make sure we do everything necessary to be in compliance.”

The public traditionally follows the exploits of lobbyists who wine and dine lawmakers, particularly during General Assembly sessions. But bureaucrats, rather than lawmakers, often are the ones making million-dollar decisions on how the state spends its $26 billion annual budget.

Building ties with state staffers

The recent ethics scandal at Georgia Tech spotlighted the relationship between companies that do business with the state and its employees.

Reports released earlier this summer said that four high-ranking, highly paid Georgia Tech administrators committed a series of ethical abuses, including receiving pay from a German company to serve on its board at the same time the company was being paid to do work for Georgia Tech and playing golf with vendors during work hours.

Georgia Tech President George P. “Bud” Peterson fired an executive vice president, and the other three resigned.

An internal report found that Paul Strouts, then-vice president of campus services, had Barnes & Noble pay $35,000 a year, starting in 2013, for a Georgia Tech football suite. Barnes & Noble operates a bookstore on campus.

University System of Georgia officials say the box was worked into the company’s commission to the school, so it would not have fallen under the heading 0f a “gift” and therefore Barnes & Noble didn’t need to file a vendor disclosure.

The coziness between the people who represent state vendors and government employees came to light in the 1990s, when Gov. Roy Barnes fired the head of the state’s purchasing agency for accepting gifts from software firms.

A state investigation found that, at a 1997 convention, a saleswoman for Oracle Corp. had given Dotty Roach a spa gift certificate worth $359 and a $540 ride in a hot-air balloon. The saleswoman later earned $450,000 in commissions after the state bought $40 million in software from Oracle and PeopleSoft Inc.

The state ethics commission fined each company $2,000 in 1999 for failing to disclose the gifts to Roach. According to longtime state officials, that may be the last time anyone has been punished for the offense.

Most gifts are outlawed

On the first day Gov. Sonny Perdue took office in 2003, he signed an executive order banning gifts worth more than $25 to state employees under his command. Gov. Nathan Deal followed suit in 2011.

Under the gift ban, employees are not allowed to take “honoraria,” or payments. An employee may accept “reasonable expenses for food, beverages, travel, lodging and registration to permit the employee’s participation in a meeting related to official or professional duties,” but he or she is supposed to file a report after such expenses are paid by an outside person or company.

“Notwithstanding this provision, the preferred practice is for agencies and not third-parties to pay such expenses,” Deal’s executive order says.

Under state law, vendors who make gifts to state employees exceeding an aggregate $250 in a year must file a report with the ethics commission. Anyone who “knowingly fails to comply with or knowingly violates” the disclosure law is guilty of a misdemeanor.

The most common “gifts” reported last year were for meals and to pay for employees to attend conferences.

For instance, SAS Institute, a multinational developer of analytics software, paid $922 each to have six Kennesaw State University professors, lecturers and administrators attend a conference last year in Washington.

SAS did $243,000 worth of business with Kennesaw State in 2017, the largest total for any of the University System schools.

Pearson Education, a publishing and assessment service that did about $10 million worth of business with state agencies and colleges in fiscal 2017, spent about $2,500 on airfare, lodging and meals for Professional Standards Commission members and college professors, mostly to attend workshops and other events.

Probably no company has been more faithful about filing reports than Georgia Power, the utility giant that was paid about $160 million by state agencies and public colleges to supply power to them in 2017. The company reported spending $13,000 on state officials, mostly for meals, refreshments and the odd desk calendar or box of candy.

Most of the meals and refreshments were spent on employees from the Georgia Department of Economic Development or the Public Service Commission, which regulates utilities.

Georgia Power bought meals or refreshments for PSC staffers more than 100 times in 2017, a year in which the agency was studying whether to allow continued construction of two nuclear reactors at the company's Plant Vogtle. The PSC eventually voted unanimously to allow the company to move forward on the project, which is far over budget and behind schedule.

Staffers recommended the commission verify and approve only $44 million of the $542 million in costs the company said were incurred from January to June 2017 and that stockholders take on any additional costs overruns deemed unreasonable by the commission. The PSC rejected those recommendations.

John Kraft, a Georgia Power spokesman, said: “We make every effort to be as transparent as possible throughout our business. We regularly meet and engage with state employees or officials on issues related to our business, and we report any expenses as appropriate.

“The Georgia Public Service Commission and Department of Economic Development are two of the state agencies that we work with every day to ensure reliable and affordable energy across the state and grow Georgia’s economy.”

Bill Edge, a spokesman for the PSC, said Georgia Power pays for meals when his agency’s staffers meet with company officials.

“They are paying for lunch for meetings with staff to talk about various issues, including Plant Vogtle, rate cases, solar and renewal energy,” Edge said.

An aberration or the norm?

It may be an aberration that vendors such as Georgia Power file every year. But it’s also unclear how many are like the National Association of Charter School Authorizers.

The nonprofit has performed work for the state Charter Schools Commission in recent years, being paid $264,000 since early 2015 to help review charter petitions and applications, for consulting services and other duties. The state commission has the power to approve or deny petitions for state charter schools and renew, nonrenew or terminate state charter school contracts.

According to agency emails, the association has offered to pay Bonnie Holliday, the commission’s director, and other senior staffers for them to attend conferences and group events since at least 2015.

The emails show Holliday and Gregg Stevens, the commission’s deputy director and general counsel, submitted reimbursements to the company to pay for travel at least four times in 2017 in amounts higher than the $250 that would trigger a requirement that the association file vendor gift disclosures.

On the day a consulting contract was being finalized in June 2017, the association offered Stevens $1,000 as a “consulting stipend” and travel reimbursement to speak at a conference. Stevens turned down the payment.

Records show the association offered Holliday a $1,000 “consulting/facilitating fee” in 2017.

Holliday provided the association with a W-9 form — which is issued by the Internal Revenue Service for a payer to obtain someone’s taxpayer identification number — on Sept. 6 of last year. In an email, the association stated that the form would be used to prepare Holliday’s “contract for work as a session manager” at an October conference in Phoenix.

Under Georgia law, “No public officer other than a public officer elected state wide shall accept a monetary fee or honorarium in excess of $100 for a speaking engagement, participation in a seminar, discussion panel, or other activity which directly relates to the official duties of that public officer or the office of that public officer.”

However, in a written response, Lauren Holcomb, the commission’s communications director, said Holliday was asked to lead a session at the conference, forcing her to develop content and an agenda, organize speakers and present information, among other duties. She said those duties were outside the scope of Holliday’s job with the state, for which she was paid $125,000 in fiscal 2017.

“Our general counsel determined that it was legal and appropriate for her to accept a stipend in this circumstance as the stipend did not fall within the definition of a ‘gift’ or ‘honoraria’ as defined by the governor’s executive order,” Holcomb said.

“In short: the stipend was provided as payment for work that fell outside the duties of her position at the SCSC — not as a gift,” Holcomb said.

William Perry of Georgia Ethics Watchdog, an Atlanta good-government group, said he was stunned a state employee would accept a stipend for taking part in a conference.

He said the lack of vendor reporting makes it easy for companies to get around more closely watched lobbyist disclosures of gifts.

“I think lobbyists use that to their advantage by allowing their client’s corporate executives to give gifts and not report it,” Perry said.

He said “ignorance of the law,” in the case of the National Association of Charter School Authorizers and other state vendors is no excuse for not following it.

“You should know if you are taking out a government employee, that has to be reported,” he said.

Vendor spending

Few companies that do business with the state report spending money on state employees for meals, gifts, etc. Below are some of the vendors who did report, and what they spent in 2017:

Georgia Power

$13,316

Mostly for meals, refreshments for Department of Economic Development, Public Service Commission employees

SAS Institute Inc.

$10,489

Mostly for public college, schools employees to attend conferences

TIAA

$7,831

Mostly public college employees, hotel lodging, meals, snacks, beverages

Google Inc.

$5,671

Mostly for public college, Department of Community Supervision officials to attend conferences, meals

Pearson Education

$2,452

Conference lodging, meals for public college and Professional Standards Commission staffers.

ACT Inc. and affiliates

$1,702

Public college employee meals and lodging

Source: Vendor filings with the state ethics commission

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured