Two months before Georgia holds its presidential primary, top state Democrats still have no clear favorite in the race for the White House — and are increasingly worried the bitter race could further strain tensions between moderates and liberals dueling for the nomination.

Many of the party's grassroots leaders are wrestling over whom to back in the field of presidential hopefuls and mindful that the internal fissures could deal lasting damage to the party's chances of flipping Georgia for the first time since 1992, dozens of activists told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

And though the leading candidates have visited Georgia multiple times to raise cash and court voters, most have yet to establish a significant on-the-ground operation in the state that will help win the March 24 primary.

An AJC poll released this week, too, underscores the muddled state of the race in Georgia. It found that three top contenders had roughly the same favorability rating among Democratic voters, weeks ahead of the start of the first nominating contests in Iowa and other early-voting states.

The prospect of a prolonged and bitter Democratic fight looms so large that many local leaders won't dare reveal their pick in hopes of preserving a sense of unity. Others are torn over which Democrat can defeat President Donald Trump, whose approval rating in Georgia hovers around 51%.

“Even in the small town of Statesboro, I feel divisions between progressives and moderates. As chair, I’m spending a lot of time talking about unity,” said Jessica Orvis, the head of the Bulloch County Democratic Party, who hasn’t settled on a candidate yet.

“Rigorous debate between progressives and moderates has the potential to either divide us or make us stronger,” Orvis said. “The fact that we’re even willing to have these debates means to me that we should wind up stronger rather than divided. Here’s hoping.”

‘Shrewdness’

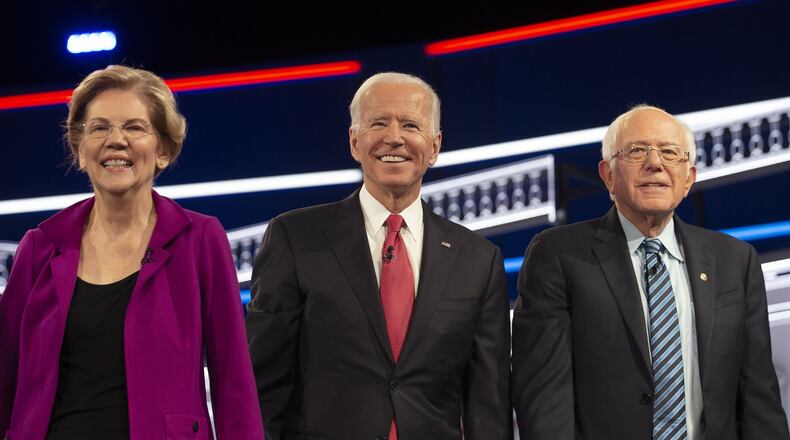

Recent polls have done little to clarify the jumbled field. An AJC poll in November showed that former Vice President Joe Biden would run strongest against Trump in a hypothetical matchup, leading the president 51% to 43%, though other contests involving U.S. Sens. Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren were also tight.

The race for prominent supporters in Georgia, another important gauge of public support, also paints an unclear picture.

Biden has amassed the largest group of endorsements from elected Georgia officials, including support this week from U.S. Rep. Sanford Bishop, who said he was impressed with the candidate's "legislative shrewdness" and record as Barack Obama's vice president.

But Bishop’s endorsement also served up a reminder that many of the state’s most prominent Democrats are still on the sidelines. That group includes the rest of Georgia’s Democratic U.S. House delegation — U.S. Reps. Hank Johnson, John Lewis, Lucy McBath and David Scott — as well as Stacey Abrams.

It was Abrams, the runner-up in the 2018 race for governor, who penned a memo that ricocheted around Washington last year declaring that it would be "strategic malpractice" if national Democrats and 2020 candidates failed to pour resources into Georgia.

So far, though, Warren is the only candidate to build a sizable campaign apparatus in the state. Her campaign has hired about a half-dozen operatives and said it plans to place staffers in metro Atlanta, Augusta, Columbus and Savannah in the next two months.

Former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg, a billionaire who is self-financing his campaign, also intends to scatter a half-dozen offices throughout the state before the March vote. He plans to take a stand in more populous places, such as Georgia, that cast ballots after the early-voting states of Iowa, New Hampshire, Nevada and South Carolina.

And the quest for campaign cash also suggests Democratic donors remain divided. A recent AJC analysis found about one-sixth of small-dollar contributors in Georgia have hedged their bets by giving to multiple contenders.

Nicole Baxby is among those who have donated to several candidates and has yet to decide whom to support. She’s worried about a replay of the bitter nomination fight in 2016 between Hillary Clinton and Sanders that exposed deep ideological fault lines within the Democratic Party.

“I believe the internal divisions will weaken the party and give the Republicans more ammunition. I also wish candidates would stop joining the race,” said Baxby, the outgoing head of the Democratic coalition in rural Harris County. “The field is overcrowded as it is.”

‘Wish list’

The momentum in Georgia could shift quickly, particularly after the first-in-the-region primary on Feb. 29 in South Carolina.

More than half of South Carolina's Democratic electorate is black, similar to the voter blocs in Georgia and other Southern states that cast ballots in March, and far more reflective of Georgia's diverse population than the overwhelmingly white states of Iowa and New Hampshire.

Georgia Democrats typically vote for the same nominee as their counterparts in South Carolina, where Biden holds a solid advantage in most polls. That's what happened in 2008, when Georgia followed South Carolina's lead in abandoning Clinton for Obama.

And four years ago, Democrats in both states powered Clinton to an overwhelming victory over Sanders, who has emerged as the dominant liberal force in the 2020 race. The simmering tension between Sanders' backers and supporters of more mainstream candidates still haunt local activists wary of the 2016 fallout.

“I personally am concerned if voters anywhere on our spectrum don’t get their candidate, they may not vote or vote third party,” said Sid Chapman, a former statewide candidate for school superintendent who heads the Spalding County Democratic apparatus.

“They all say they will vote for the nominee, but we know that didn’t happen in 2016,” said Chapman, who recalls the internal turmoil in 2016 when he was a delegate for Clinton’s campaign. “I’m afraid this affected the general election outcome. I pray we get over that and elect our nominee.”

Jacquelyn Bettadapur, the chairwoman of the Cobb County Democratic Committee, tells fellow activists that the contest should "not be about a progressive policy wish list." She'd rather hear about how to build a sustainable economy and narrow the income gap than free college tuition.

“This election is existential. Our democratic institutions and constitutional government are under threat and may have already suffered irreparable damage,” she said. “First, we must right the ship. First, we have to beat Trump. Then we have the luxury to debate the merits of progressive policy.”

Still, those promises of Medicare for All and free tuition for higher education have captured the energy and enthusiasm of many on-the-ground activists. Randy Goss of Peach County initially backed U.S. Sen. Kamala Harris, who dropped out of the race, but he is now drawn toward Warren.

“Iron sharpens iron and I don’t think (any of the candidates) truly hate each other,” Goss, a Democratic official in the Middle Georgia county, said of the ongoing intraparty clash. “Factions exist in all circles — politics or nonpolitical.”

‘Circular firing squad’

The rhetoric is so polarizing that some shift their focus elsewhere.

In Upson County, one of only a handful of rural Georgia counties that have trended Democratic from 2016 to 2018, party committee Chairman Chris Benton is spending his time recruiting candidates to run for local office rather than focusing on national politics.

“I like the odds of every single Democrat versus Trump,” he said. “Some internal division is to be expected. We’re not always going to agree on policy, but we should agree on our vision.”

Count Dutton Morehouse, too, among the fretful. He doesn’t yet have a favorite candidate but is in search of a “moderate in the Bill Clinton model” who could rise above the din.

“I am concerned that the Democrats are giving the appearance of a circular firing squad,” he said. “We don’t have a lot of time to sort it all out.”

Melissa Hopkinson, a leading Democratic activist in Oconee County and co-chairwoman of the local party, also said she worries the nominating contest is not as “clarifying” as she hoped it would be. But she prefers to see the bright side of a drawn-out battle.

“The one good thing about this long lead-up to the primaries,” Hopkinson said, “is that it has forced the Democratic Party to have a discussion about its internal differences.”

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured