Coronavirus to test Georgia’s chronic health gaps

Earlier this week, Public Health Commissioner Kathleen Toomey stood with Gov. Brian Kemp to announce that COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus, had come to Georgia.

Two patients, diagnosed and isolated quickly, were marking time in home recovery. The virus, they said, was being faced down exactly as planned.

» THE LATEST: Complete coverage of coronavirus in Georgia

“Everything about this situation demonstrates how well the system is working,” Toomey told assembled cameras and thousands of Georgians watching live.

In the days since that announcement, Georgia’s health officials and state leaders have been laser focused on messaging calm to the public: There is no widespread infection here, and most people who do get the illness are not likely to suffer serious harm.

CORONAVIRUS TIPS

CDC recommends preventive actions to help prevent the spread of respiratory diseases:

• Avoid close contact with people who are sick.

• Avoid touching your eyes, nose, and mouth.

• Stay home when you are sick.

• Cover your cough or sneeze with a tissue, then throw the tissue in the trash.

• Clean and disinfect frequently touched objects and surfaces using a regular household cleaning spray or wipe.

• CDC does not recommend that people who are well wear a facemask to protect themselves from respiratory diseases, including COVID-19. Facemasks should be used by people who show symptoms of COVID-19 to help prevent the spread of the disease to others. The use of facemasks is also crucial for health workers and people who are taking care of someone in close settings (at home or in a health care facility).

• Wash your hands often with soap and water for at least 20 seconds, especially after going to the bathroom; before eating; and after blowing your nose, coughing, or sneezing. If soap and water are not readily available, use an alcohol-based hand sanitizer with at least 60% alcohol. Always wash hands with soap and water if hands are visibly dirty.

• If you are concerned you might have the coronavirus, call your healthcare provider before going to a hospital or clinic. In mild cases, your doctor might give you advice on how to treat symptoms at home without seeing you in person, which would reduce the number of people you expose. But in more severe cases an urgent care center or hospital would benefit from advance warning because they can prepare for your arrival. For example, they may want you to enter a special entrance, so you don’t expose others.

Source: CDC

But beneath the surface, Georgia’s health infrastructure has longstanding weaknesses. The best defense against the coronavirus is the good underlying health of the patient, and the best way to contain an outbreak is a quick response, but Georgians face unusual challenges in these regards. They are less likely to have health insurance than most other Americans, and some areas of the state have sparse medical care. Seven rural Georgia hospitals have closed in the last decade.

At times, even in areas where there is an abundance of medical care, there is also an abundance of patients, straining the system beyond its capacity. Atlanta’s main safety net hospital regularly rents an extra ER trailer for the flu.

Dr. Tom Frieden, CEO of Resolve to Save Lives, resided in Georgia for eight years as he headed the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In an interview with The Atlanta Journal-Constitution about the coronavirus, he acknowledged the state’s shortcomings as well as its strengths: a capital packed with some of the world’s best disease fighters. He also pushed back at immediate worry for Georgia counties without doctors.

“The current risk of this infection to the overwhelming majority of Americans is minuscule; it’s currently not spreading widely,” Frieden said.

However, he added, lack of access to health care in parts of Georgia has a domino effect that heightens the risk of the coronavirus here. It impedes treatment of underlying diseases, like diabetes, and diabetes worsens the impact of infections like the coronavirus. If people show symptoms, he said, they are less likely to seek care promptly if they don’t have insurance. Therefore, they may be more likely to spread the disease before getting tested.

“I think both the lack of access to primary health care and the lack of primary health care capacity is a big problem,” Frieden said.

Unknowns

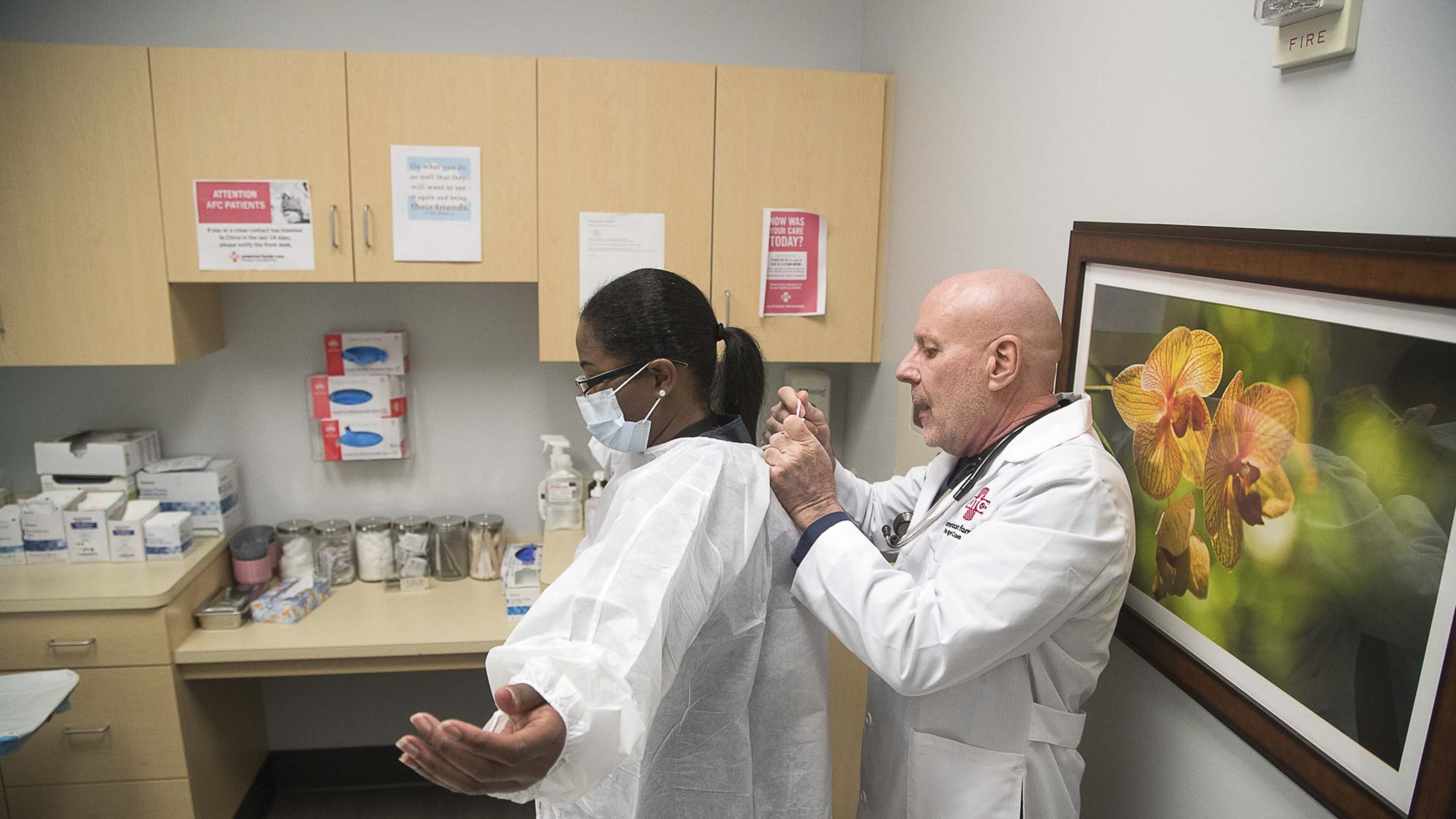

Dr. John Destito, regional medical director for American Family Care, oversees five clinics in metro Atlanta. He went through the ebola threat in 2014 and knows the drill for epidemics. Within the last couple weeks, the company’s computer intake system has been programmed to ask each patient questions related to the coronavirus: Have you traveled recently? Where? Is the patient coughing?

» RELATED: Georgia to ramp up testing, screening after first cases of coronavirus

» MORE: Metro Atlanta jails ramp up precautions as coronavirus fears grow

With maybe a half-dozen patients, he said, it got to the point where they called public health officials to see if a coronavirus test was necessary. They were told none of the patients needed one, he said.

State employees who answer those phones and help make that determination cost money. So do the state epidemiology staffers who spent this week tracking down those who were in contact with the father and teenage son diagnosed in Georgia.

The governor has proposed cuts to the state public health budget.

Toomey said any cuts wouldn’t affect those services and that the state public health department can still meet current demands. And, if demands were to increase because of a potential epidemic here, Kemp said, “That’s what we have emergency funds for.”

The pathogen is new, and no one really knows exactly how widely it will spread, how long it will last, or how much — or how little — damage it will do.

That makes planning tough.

It also feeds into public fear that makes planning tougher.

In her Conyers clinic, Dr. Theresa Jacobs has been seeing patients who believe they’re infected although they have not traveled anywhere near the affected countries and have no risk factors.

A mother came in with her daughter, who was wearing a mask. When Jacobs asked why, “The mom said, ‘She doesn’t want to get coronavirus.’”

The girl was 12 or 13. Experts say children are at lower risk of harm from the disease, and some who get infected don’t even get symptoms. “It was the perfect time to do education,” Jacobs said. “Number one, the mask she had on would not protect from coronavirus.”

» CONTINUING COVERAGE: How to protect yourself from coronavirus

» THE LATEST: Map tracks spread of coronavirus in real time

That hasn’t stopped people from buying those standard medical masks and other supplies, making them scarce.

Jimmy Lewis — whose business, Hometown Health, helps small hospitals lobby the Legislature and navigate state finances — sent out a letter to his members warning of emerging supply shortages. He’s heard from clients trying to ramp up that they are simply unable to find regular supplies from their usual suppliers, including Amazon.

“This is going to be an actual supply and demand issue,” Lewis said. “They’re going to have to figure it out as it comes down the supply chain — and sooner rather than later.”

Lewis has been in the business for decades and says this is the first time he’s seen this.

In metro Atlanta, home of some of the world’s best health care, there are supply and demand issues but of a different kind.

The specter of a system strained to its limit, with emergency rooms so full they turn away ambulances, isn’t movie fantasy here. It’s already happening when there are big emergencies like the Grady Memorial Hospital water main break.

“Most places are always almost full,” said Adrianne Feinberg, director of emergency preparedness for the Georgia Hospital Association.

However, Feinberg said, those big hospitals do what it takes in an emergency. She recalled the 2009 H1N1 pandemic, when some metro Atlanta hospitals had ER patients with flu symptoms wait in their cars for their appointments. Other hospitals set up additional screening locations outside the main building.

“People did creative things,” Feinberg said. “It’s important to know we would do what it takes.”

Best-case scenario

The health care deserts in rural Georgia have worried lawmakers for years. Nine Georgia counties have no doctor at all.

Georgia has a high rate of diabetes, one of the conditions that make it more difficult to fight the coronavirus. Older people are more at risk generally. And, in Georgia, more than one-quarter of adults over 65 have diabetes, according to the CDC.

State leaders note that every county has a public health office that can ramp up for cases like this.

They also are trying to create incentives, such as paying school loans, for doctors and nurses to go to rural locations. They’ve funded training programs. To get more chronic disease patients under care, they’ve suggested telemedicine.

The money isn’t there to blanket the state in a game-changing way with doctors, or high-speed internet and devices to stream doctors.

This year, a proposed increase in funding to repay school loans was eliminated amid larger state budget cuts.

In contrast, Georgia’s first coronavirus patients live in Fulton County, where there are more than 4,600 doctors actively practicing medicine.

The father flew in from virus-struck Italy and watched for symptoms. When he felt sick, he quickly called his doctor, who arranged for a weekend test. The man was ushered through a special entrance so as not to endanger other patients. The doctor then called health officials, who zipped the test over to the CDC. The result was confirmed, and he and his son — who also tested positive — are properly quarantined at home.

The state’s public health preparedness deserves some credit for that, said Curt Harris, director of the Institute for Disaster Management at the University of Georgia. And he agreed with Frieden that most people, at this point, should not be afraid. They should take measures like covering their cough and washing hands.

But, he and others concede, there is a long way to go.

“We think it’s going to be very difficult if not impossible to try to contain it, to put it back in the bag,” said Frieden. “But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try.”