Politicians deem video gambling industry ‘respectable’ again

The tale of video gambling in Georgia could be that of Lazarus, the Biblical story of the man raised for the dead. It could be the parable of the Prodigal Son, an outcast welcomed back with open arms.

Or maybe it’s just that old adage “money talks.”

A small group of Georgians spent handsomely on Gov. Nathan Deal and state lawmakers in the months leading up to new laws regulating coin-operated amusement machines — essentially, slot machines. In return, the industry was allowed to come out of the shadows with legislation placing its regulation with the Georgia Lottery Corp.

These machines, once nearly outlawed in Georgia, now represent a fully regulated industry and one even deemed “respectable” by political leaders. And the small group of industry insiders that helped forge the rules — machines owners, known as “master” licensees — got favorable guarantees. Among them, lawmakers capped new competition and required convenience store owners and other locations that lease machines to arbitrate disputes with master licensees, rather than going to court.

State Sen. Butch Miller believes that regulators have made great progress in cleaning up a shady industry. The Gainesville Republican, who is Gov. Deal’s Senate floor leader, sponsored Senate Bill 190, the regulatory bill favored by some industry insiders that passed the Legislature this spring.

“The coin-operated amusement industry is an industry that is deserving of regulation and management by the state,” he said. “This industry has proven over the last couple of years to be very responsible and very productive for the Lottery.”

But some say the state gave a gift to a small group of people who stand to make millions. State officials estimate the industry brings in anywhere from $200 million to more than $600 million a year in revenue.

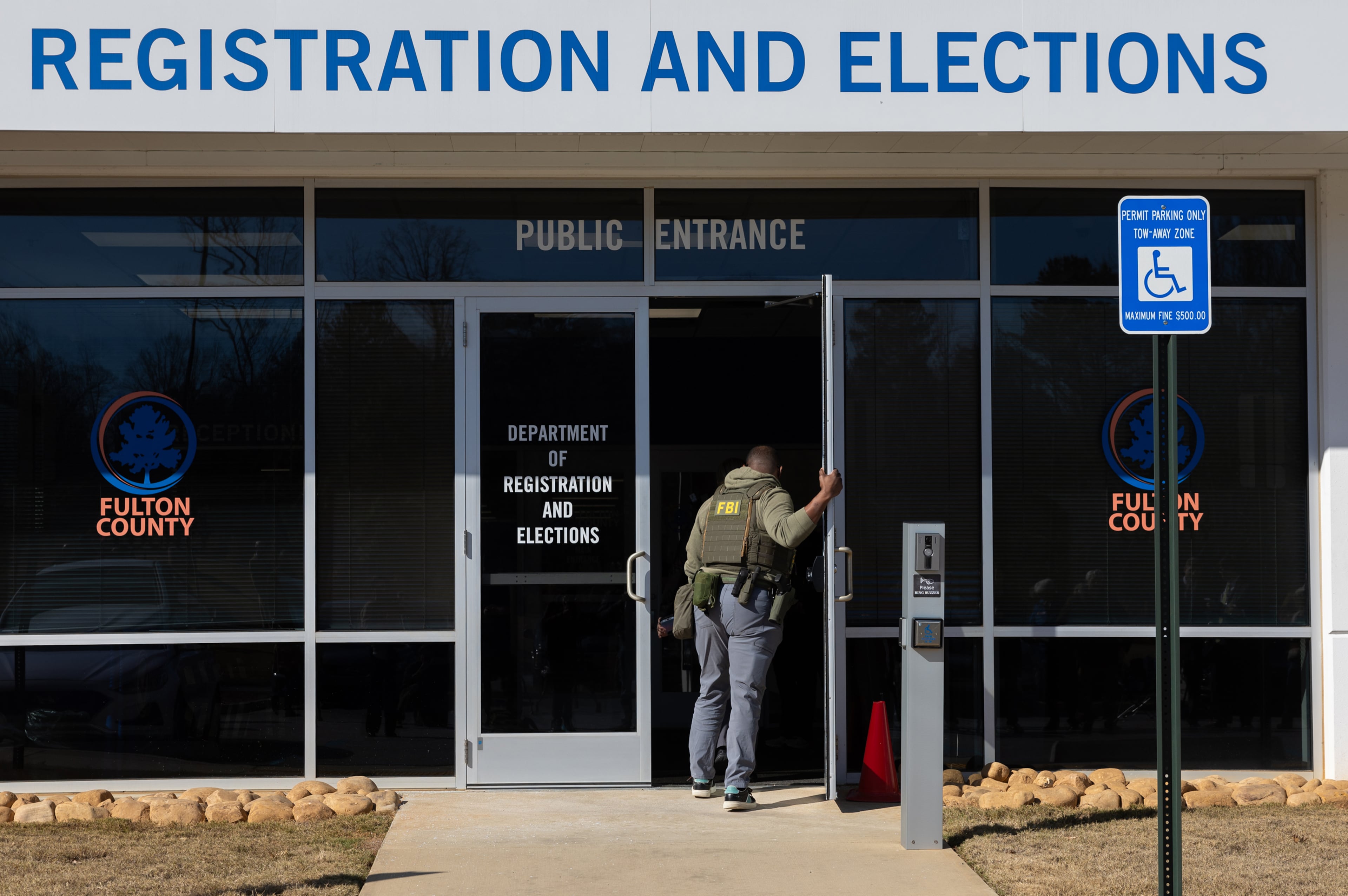

And while Lottery officials believe the industry can be regulated into being law-abiding, law enforcement raids are common, like the one last month in Thomaston that resulted in a dozen arrests for allegedly paying out cash jackpots, instead of store credit.

Once nearly outlawed

The decision to more deeply regulate, rather than outlaw, video gambling is a head-shaking development to one of the business’s greatest foes, former Gov. Roy Barnes.

In 2001, Barnes, a Democrat, attempted to personally usher video gambling out of the state, orchestrating a forceful, populist campaign against the machines that he called a “cancer” on the state.

Barnes was reacting to a ban passed the prior year in South Carolina that pushed thousands of the machines across the border into Georgia. A GBI report at the time said of the approximately 20,000 of the machines in Georgia at the time, an estimated one in five were involved in making illegal cash payouts to winners while raking in more than $1 billion a year in profits.

Barnes said video gambling industry has crawled back from the brink with the help of state lawmakers. Now, the state has about 25,000 of the machines.

“Moving it over (to the Lottery) and regulating it is exactly what (gambling interests) wanted to do because it legitimizes it rather than making it contraband,” he said. “It’s shocking to me that a Capitol dominated by or calling themselves social conservatives have legalized over a few years the widest spread gambling in this state – and it’s growing.”

Given the willingness by state leaders to legitimize video gambling, Barnes said it unsurprising that casino interests like MGM are now targeting Georgia for possible larger-scale development.

Many lawmakers in this political generation, however, do not consider playing the machines to be “gambling.”

“In my view, no,” Miller said. “It’s no more gambling than the Lottery is gambling.”

While Miller understands the coin-operated amusement industry has its “bad actors,” he said efforts to outlaw the machines did nothing more than to push them deeper into the shadows.

“I knew people in the industry and knew them to be respectable and I knew they wanted nothing but to be respectable,” he said.

Welcoming (and influencing) regulation

Lee Hunter, owner of a Mableton-based business that has one of the largest stables of machines in the state, said the industry welcomes regulation “with open arms,” in part because it has taken 15 years for video gambling to recover from its near-death experience.

Barnes’ ban was “a miserable failure,” Hunter said.

“We’ve all lived through the draconian policies of past administrations when the answer was let’s just ban all the machines,” said Hunter, who also leads an advisory board working with the Lottery to help with the transition. “It drives them underground.”

Not only have industry leaders welcomed regulation, they have helped shape it. In a statement, trade group The Georgia Amusement and Music Operators Association said industry figures “proactively reach out to stakeholders in an effort to further clean up the industry.”

Increasingly,that outreach has meant money to key politicians.

In the 2014 campaign, a handful of the state’s top “master” licensees — the state’s required license for owners of the video gambling machines — showered Georgia politicians with at least $83,000 in campaign donations. Hunter and his wife, for instance, chipped in $31,850 for the 2014 election campaign, including giving the maximum contribution to Gov. Nathan Deal and a $10,000 gift to the state GOP.

The industry put at least $141,000 into the 2014 campaign – more than the prior five election cycles combined. GAMOA also formed its own political action committee in 2014 and in short order the PAC had contributed nearly $60,000 to politicians, including $7,300 to Deal’s reelection.

In their statement GAMOA said little about their giving except that it was non-partisan and “in compliance with Georgia law.”

Gifts targeted members of the House and Senate Regulated Industries committees, the leaders of each chamber and SB 190 sponsor Miller. In fact, Miller’s single largest contributors are industry leader Lonnie Pope and his wife, who live in Gainesville.

Miller said he was unaware the Popes were his largest individual contributor but said he was not surprised.

“The Pope family and my family have known each other for 30 years,” he said. Regardless, he said the combined contributions from the Popes is a small fraction of his overall fund raising.

Dissension in the ranks

But there are contentious relationships among many in the industry, and the new regulations don’t sit well with all.

Those who were not a part of the select group who gave so generously to Deal and other top leaders say they have been frozen out of the discussion about the rules.

Many are among a growing Indian community within the industry who first saw the new regulations as both an opportunity to go into business and to expand it with updated machines and technology. They saw room for improvement with “better electronics, better service, better graphics,” said attorney Mark Spix, who helped some break into the industry.

But those who have controlled the industry for decades have shut them out, he said.

“They were not the reigning monopolists of the industry,” Spix said.

Lawmakers in 2013 for the first time mandated that revenue be split evenly between machine owners leasing game machines to business locations and owners of the locations themselves (with a small percentage of that total kept by the state).

The immediate effect for some was competition between machines owners for new locations. That competition led to an ongoing industry lawsuit over how to handle legal contracts made before the new rules were in place, with industry leaders suing newcomers they accused of undercutting them.

Lawmakers picked sides this year when, in SB 190, they said the law was not intended to void existing contracts that previously allocated revenue other than a 50/50 split. That favored the old guard. The Legislature also mandated arbitration in industry disputes. Lottery officials have so far decided to sole-source that business to only one arbitration company.

Ricky Virani — who in 2013 formed a company to supply gaming machines to convenience stores and was one of the master licenses sued over the contracts — said the Lottery needs to work with a broader group within the industry as it moves ahead, something “that has a voice for everybody and not a voice for just 5 or 10 people,” Virani said.

GAMOA said the organization has more than 150 master licensee members, making it one of the largest gaming trade organizations in the nation.

But the Lottery is keeping the number of master licensees small. SB 190 capped the number of master licenses at 220 statewide.

Currently, the Lottery has issued 209 master licensees, with some people holding more than one license. The recently passed legislation will allow the state to auction off the remaining licensees.

Joseph Kim, senior vice president and general counsel for the Lottery, said keeping a limit on number of master licensees will assist the Lottery in regulating the industry. However, much of the regulatory trouble happens at convenience stores and other locations where the machines are placed, and there are more than 5,000 licensed locations and no cap on more.

Cap or no cap, Barnes said he believes the state created an opportunity for corruption and organized crime by allowing video gambling to expand in the state.

“You’ve opened this door. You’ve opened it very wide,” he said. “You might as well have sent an engraved invitation to some very unsavory parts of our society that are looking for places where there is a lot of cash.”

Online exclusive:

A small group of Georgians dominates what the state calls the coin-operated amusement machine industry. At myAJC.com, we tell you who they are. Also online, find out where the games are located and read our Sunday story on the Georgia Lottery’s struggle to bring integrity to rein in the industry’s rogue operators.