When voters pick their final nominees for the November elections on Tuesday, they’ll do so after being overwhelmed by TV and radio ads, social media messaging and mailings from groups they’ve probably never heard of.

Outfits such as Changing Georgia’s Future or PowerPAC or Black PAC or Conservatives for a Stronger Georgia or Higher Heights for Georgia or the Hometown Freedom Action Network or Insuring America’s Future.

In total, 18 such “independent” committees raised about $7.5 million for the primaries and runoffs, and they — and many others who recently filed paperwork — will likely play a major role in the fall elections as well.

The gubernatorial candidates have already raised a record $33 million for this year's campaign, but going forward, the sky's the limit for "independent" committees.

“Come September, you are not going to see any commercials around here unless they are paid for by an independent committee,” said Rick Thompson, a former executive director of the state ethics commission who has set up dozens of politically oriented nonprofits and funds.

Both of the Republican gubernatorial candidates in Tuesday’s runoffs — Lt. Gov. Casey Cagle and Secretary of State Brian Kemp — received help from “independent” committees.

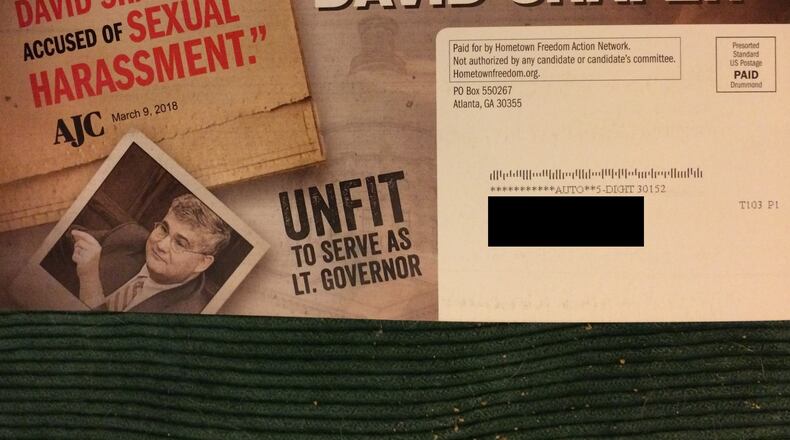

In the lieutenant governor's race, an out-of-state "independent" group put about $1.5 million into trashing state Sen. David Shafer, only to be countered by $1 million from another "independent" committee supporting Shafer.

At least seven such committees — raising about $2.8 million — have backed former state House Minority Leader Stacey Abrams, the Democratic nominee for governor. Other committees that have filed paperwork to raise money are also likely to throw in for Abrams this fall.

While “independent” committees have been around for years, election watchers say there has been a proliferation of them in 2018 as both parties faced heated primaries to fill open seats in several key races. Gov. Nathan Deal is being term-limited into retirement, and the lieutenant governor, secretary of state and insurance commissioner are either running for other offices or calling it quits, so those jobs are open, too.

Donors can give a limited amount to candidates — about $17,000 for the primary, runoff and general election races combined — but there are no limits on how much they can give to “independent” committees or to the groups that fund them.

One group supporting Cagle, for instance, received donations of up to $100,000 a pop from nursing home owners, oil companies, lobbying groups, car dealers and others interested in state legislation and funding. It's unclear whether any of that money made its way to the "independent" committee backing his candidacy.

One of the committees supporting Abrams received a $1 million contribution from San Francisco mega-donor Susan Sandler.

Legally, the committees can’t coordinate directly with campaigns, but they can and do support candidates. Depending on how they are set up and where the money comes from, some committees disclose their donors. Others shield donors by taking money from other organizations that, by law, don’t have to disclose where they got the money.

For instance, PowerPAC, which supported Abrams, reported that $1 million contribution from Sandler, the bulk of what it collected. Black PAC, another fund helping Abrams, reported $1.1 million in contributions for its Georgia committee, disclosed $400,000 from another mega-donor, New Yorker George Soros, and about $330,000 from Emily’s List’s Women Vote! campaign.

By contrast, a committee running ads for Cagle in the Republican runoff has reported raising about $1.5 million, but about $900,000 of that came from Citizens for Georgia's Future, an entity headed by two top statehouse lobbyists that doesn't disclose its donors to the state.

Kemp's campaign has received help from a committee that has reported only one contribution: $200,000 from Virginia-based Citizens for a Working America, which discloses almost nothing about itself, including donors.

The Washington-based Hometown Freedom Action Network reported about $1.5 million in contributions to spend on advertising attacking Shafer. Almost all the money also came from Citizens for a Working America.

In response, another group, Conservatives for a Stronger Georgia, put $1.1 million into backing Shafer against his runoff opponent, former state Rep. Geoff Duncan. Most of the money came from the Republican Leadership Fund of Georgia, a lobbyist-run organization that got most of its money from a $1 million contribution Shafer's state Senate campaign made last year.

If that’s all confusing, that’s the way some politicians, donors and the people who set up funds like it. More and more candidates, lawmakers and political organizations set up political funds — sometimes called “social welfare” organizations — that are allowed to hide the identity of donors.

Some say allowing anonymity permits donors to give without fear of retribution if they wind up on the wrong side of an election. Good-government types say the public has a right to know who is trying to influence their vote.

William Perry of Georgia Ethics Watchdogs filed ethics complaints over the Hometown Freedom Action Network's spending against Shafer because Citizens for a Working America didn't disclose where its money came from. His complaints also accuse a former state senator who was once a Shafer rival of funding the organization but not disclosing it, a charge the ex-lawmaker denied.

“This is the future,” Perry said. “People are taking full advantage of the law to hide the money they are funneling into campaigns. At the end of the day, it’s more people finding ways to hide money.”

The state ethics commission made it clear last fall that it would take a closer look at such groups to make sure they are following Georgia law.

“It’s going to be interesting to see if Georgia laws were crafted in a way that allows this,” Perry said, “because it almost doesn’t seem like (the groups) are covering their tracks well enough.”

Any review probably wouldn’t produce anything until after the 2018 elections, meaning it won’t have any effect on the fall races.

Chip Lake, a Republican consultant working for Duncan, called the proliferation of “independent” groups “an evolution of how races will be run.”

“The reality is state campaign finance laws seem to give more flexibility to the outside committee concept than federal law allows,” Lake said. “I think what we are seeing in the primary (and runoff) campaigns is going to be a reflection of what we are going to see in the general elections.

“Is it good for voters? To be determined. There will be plenty of information in the public domain that voters can absorb to become informed about which candidates they want to go vote for. I think the more information out there, the better.”

2018 campaign

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution is covering the issues and candidates in a busy election year. Gun rights, immigration and tax policy were all issues that factored in the results of the Georgia primary, and they were all stories the AJC covered in the run-up to the vote. Look for more at PoliticallyGeorgia.com as the state approaches the next political milepost, the July 24 runoff.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured