On April 12 last year, an investigator for the insurance giant Blue Cross Blue Shield sent a bombshell letter to the owner of a small North Georgia hospital, Chestatee Regional. The investigator laid out evidence of systemic overcharging for urine drug tests, tests that he suggested the Dahlonega facility never should have done in the first place — and maybe never did, at all.

The letter touched off a drama that has endangered the hospital and landed it in federal court. It has also cast shadows on another Georgia hospital 200 miles away that is owned by the same man.

And it has served up lessons for many more Georgia hospitals, facilities that increasingly struggle to make ends meet in rural areas and sometimes turn desperate for cash.

The hospital’s owner, a Florida lawyer named Aaron Durall, through his company Durall Capital Holdings, denies impropriety but is now on track to sell Chestatee Regional and shut it down. Its 200 employees will receive no severance and no guarantee of rehire should new owners reopen. Unless it’s replaced, the county will have no hospital or emergency room. To top it off, a national news network has just aired accusations from a 2016 whistleblower lawsuit alleging its drug screen business was a scam; the whistleblower’s lawyers later dropped it without a resolution, saying she couldn’t afford to proceed.

The issue landed like a bomb on the desk of newly elected Dahlonega Mayor Sam Norton.

“Rural communities are at a huge disadvantage compared to metro communities in general,” he said. “The hospital was one of our largest employers.”

The Blue Cross lawsuit was filed March 28 against Durall and two of his Florida business associates, and Durall companies including Reliance Laboratory Testing and Chestatee Regional Hospital. In the suit, lawyers for Blue Cross parent company Anthem Inc. and 18 Blue Cross affiliates from as far away as California accuse them of using Chestatee to reap more than $110 million in improper testing fees.

They want it all back.

A statewide struggle

In statements to The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, Durall denied wrongdoing. No court has yet ruled on the Blue Cross suit. And Durall says the whistleblower's allegations, aired on CBS, were "flatly wrong," as is "any allegation that the labs were not processed at Chestatee Regional Hospital."

Instead, Durall says, he’s motivated not just by profit but by a desire to maintain care for the people in the community.

When Durall bought Chestatee from the SunLink Co. in August 2016, it was already struggling. That's no surprise. Seven rural Georgia hospitals have closed since 2010. A legislative committee last year found that 10 out of 50 rural Georgia hospitals were financially viable.

Consultants, lobbyists, politicians and hospital managers have looked for business ideas to save them. Some have tried beefing up obstetrics services, but like Emanuel Medical Center, they eventually had to cut the service for lack of population growth and rural obstetricians. The Legislature has passed a bill allowing "micro-hospitals," but it is not expected to have wide impact. Hospitals such as those in Dodge County and Berrien County see hope from geriatric psychiatric programs.

Hospitals just need the money.

Experts often cite the Affordable Care Act and the state's response as one of the reasons. Georgia's reluctance to expand Medicaid after the ACA assumed states would has left hundreds of thousands of poor adults without medical coverage. But that doesn't stop them from showing up in emergency rooms.

Furthermore, reimbursement levels for both Medicaid and Medicare (the federal health care programs for the poor and the elderly) often don’t meet costs. Rural hospitals treat large numbers of those patients. But they often don’t draw the higher-income, privately insured patients that metropolitan hospitals can to balance out those losses.

In the end the problem affects metro residents, too. A state’s overall health care adequacy matters to big companies that are thinking of relocating to a capital. And rural hospital failures will mean pressure on metro facilities to care for some of those people who find themselves without care and, eventually, pressure on state taxpayers to step in.

Durall was not only a lawyer but a medical lab president, and he brought his own idea to rural Georgia: fund hospital operations with lab tests.

Hospitals typically charge more for everything, since they’re trying to spread the costs from enormously expensive services such as emergency rooms across the entire operation. Insurance companies understand that if a patient shows up overdosed in the ER and is tested for drugs in the hospital lab, that test will be much more expensive than if the test were mailed from, say, an employment office to a stand-alone lab company.

And they pay it. Durall’s private lab company would typically receive $100 to $300 from Blue Cross for a specimen test, the suit says. Chestatee got more than $1,400.

What Blue Cross seems not to have contemplated is what it says Durall did, turning a hospital with a lab into a lab supporting a hospital.

Scam or smart strategy?

Almost as soon as Durall bought Chestatee, Blue Cross says, bills started rolling in from the hospital’s lab for patients of pain clinics and rehab centers, who require frequent drug testing.

According to the lawsuit, before Durall bought it, Chestatee billed Blue Cross for about 30 urine drug tests per month. After, that rose to 4,800 urine drug tests per month. Blue Cross called the increase “staggering.”

That’s not all. The company says it saw misrepresentations such as admission type marked as “urgent” when no patient was admitted at all. The lawsuit made the case that not only were the patients not from Chestatee, but many of the lab tests weren’t done there either.

The suit suggested that the lab doing the testing was often Durall’s own Florida-based lab company, Reliance. Some of those specimens may have gone on to Chestatee for additional testing, the suit added, but not necessary testing. Cases often showed retesting ordered before the patient’s doctor received results from the first test, according to the suit.

The suit alleged a sweetener for the clinics and other treatment providers to come to Durall et al.: the promise of “kickbacks” — for example, a share of the generous insurance reimbursement.

When Blue Cross’ investigator called Chestatee, he got an earful from a suspicious employee there. Then Durall’s associates in Florida, who handled the Georgia hospital’s billing and records, allegedly told the employees to stop talking.

The initial lawsuit is not airtight. Some of its accusations rest on documented evidence, but others are sprinkled with the caveat “upon information and belief.”

Durall wrote to the AJC that his attorneys would “vigorously” defend him and his co-defendants against the lawsuit, and would answer its claims in detail in court.

Chestatee “expects to be successful in any dispute related to the (laboratory billing) issue,” he said.

“The Hospital billed only for any services performed by Hospital staff at the Hospital,” he wrote, “and the payers correctly paid the Hospital for those services.”

But that won’t save the hospital, at least in its current form.

Durall is now selling Chestatee. The terms of the deal mandate its closure, at least for a time. The potential buyer wants to ensure that any liabilities of Durall’s are not passed on to it.

The planned closure, announced two weeks ago, dominated the front page of The Dahlonega Nugget.

Onward

And yet, Durall is not done. His ambitions stayed in Georgia but moved 200 miles south.

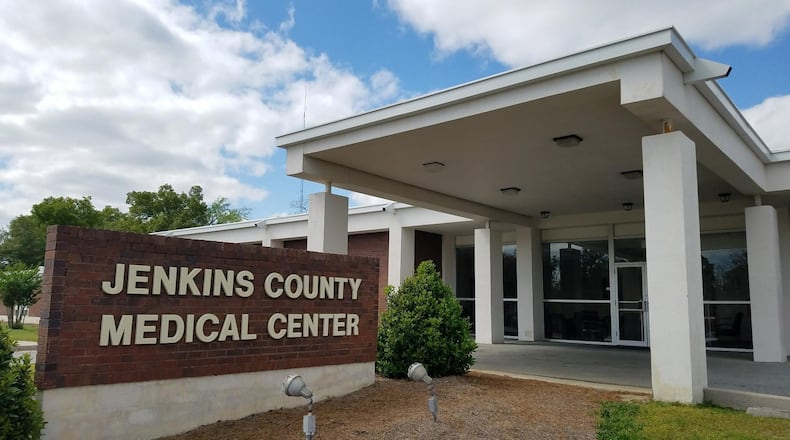

Within weeks of the investigator's letter last year, Durall formed a new company and bought Jenkins County Medical Center in Millen, population 3,120: also distressed, also small. And also saved by the money from his business plan to profit from drug tests.

“This is no secret, it’s exactly what he told us he was doing,” said Jeff Brantley, the Millen city manager. Brantley and other community leaders are periodically briefed by an administrator Durall hired for the hospital.

They said the patients may not come from the hospital, but the tests are done there. Brantley has seen from his office window the new equipment unloaded in the hospital lot below.

“What they’re doing is not illegal,” he said. “The hospital here actually has bought a lot of new lab equipment and they’re running labs here, probably 1,500 or more a month.” Durall also is setting up a geriatric psychiatry service.

But when their hospital owner showed up on national TV dodging news cameras this spring, the folks in Jenkins County noticed.

"You couldn't help but be concerned," said King Rocker, the mayor of Millen. "But we've been assured … that they were OK."

Brantley has been briefed on the newscast allegations and Durall’s response. But when a reporter for the AJC contacted Brantley the week after the Blue Cross lawsuit was filed, Brantley said he didn’t know about that.

‘It’s so important’

The stakes for the county are high. A rural community’s hospital is often its economic anchor, a rare locus of skilled employment. One analysis local leaders cite found that when Jenkins County funded the hospital with $4 million per year, $11 million was pumped back into the county economy.

“If you look around the country, you see how many rural hospitals are closing or struggling,” Brantley said. “This community needs the emergency room. Emergency rooms alone are not profitable. So the hospital has to, of course, make money other ways to stay open.”

The hospital now feels on an upswing. The outside has been refurbished. The parking lot is to be repaved. Equipment and registration for the geriatric psychiatric care program are a done deal.

Beth Rocker is glad. Before her father died, he was a patient at Jenkins County Medical Center. She remembers visiting him while she was also helping her daughter plan her wedding. It was overwhelming enough without having him hospitalized in another city such as Augusta.

“I was able to do things at home and be with him several times a day; and he got good care,” said Rocker, who co-owns an insurance agency and is married to the mayor. “There are people who don’t have access to get to Augusta, especially the elderly.”

Mandy Underwood agrees. Her job as executive director of Jenkins County’s development authority and chamber of commerce is to try to lure jobs and build economic development. Business prospects always want to hear about the hospital, she said. They need the care for their workers. And especially in manufacturing, they need to know they can get their personnel’s drug test specimens drawn nearby (though they’re then sent on to cheaper labs for analysis). One prospective employer even toured the hospital.

When the hospital's private owner announced on April 25 last year that it would close the facility, she despaired. "How can I recruit without a hospital?" she thought.

But Durall appeared and despair turned to hope.

“It was like a savior,” Underwood said. “That’s how we looked at it. Our knight in shining armor came in and saved our hospital. It was great for us. It was all about the services.”

When Jenkins County Medical Center became available last year, Durall had just received the Blue Cross letter about Chestatee up north.

That fall, after what he describes as months searching for buyers, Durall approached Northeast Georgia Health System to ask whether it was interested in buying Chestatee. It was; it has land a few miles away along Ga. 400 and might use Chestatee’s hospital certificate to move some kind of health care facility over there. Meanwhile, the Chestatee property might be used by the local university. Durall told the AJC his move was “with the needs of the community in mind … to protect the future of health care for Lumpkin County.”

If the due diligence period goes as currently planned, Chestatee Regional Hospital will close its doors July 31. Then the new buyer will analyze the market to see whether and what to rebuild.

Stay on top of what’s happening in Georgia government and politics at PoliticallyGeorgia.com.

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured