Nearly a decade ago the Great Recession and concerns about sparse attendance ended the state’s financial support for money-losing Georgia halls of fame.

But the General Assembly this year — in a small way — put itself back into a business that used to cost millions of dollars a year.

The lone survivor of the hall-of-fame purge, the Georgia Sports Hall of Fame, remained open largely through local government funding and private donations. It is budgeted to receive marketing funding from the state as part of the spending plan lawmakers approved for fiscal 2020, which begins July 1.

Hall officials hope the relatively small allocation — $50,000 — is the start of longer-term state backing. And it could ignite a move for the state to back other similar facilities.

The grant comes at a time when the General Assembly, which is largely led by politicians from small towns, has been pumping up funding for programs outside metro Atlanta in hopes of improving the region’s economy

"I think the Sports Hall of Fame funding is important for tourism, especially for Middle Georgia and all of Georgia to promote the state as a place where great athletes come from," said Senate Rules Chairman Jeff Mulls, R-Chickamauga, who co-sponsored legislation promoting the site this session. "Tourism is economic development, and tourism creates jobs."

But some of the dynamics that led the state to stop funding in the first place — such as low attendance and a location not likely to draw destination visitors — remain.

“They are not going to draw people to that destination unless you have a major national or international hall,” said Ben Harbin, the former chairman of the House Appropriations Committee who saw his own area, Augusta, lose state funding for the Golf Hall of Fame when he was in office. “It has a very limited pool of visitors to draw from.”

The state went into the hall of fame and museum business in a big way during the 1990s, approving more than $20 million in bonds to build Sports, Golf and Music halls, and spending millions more to run those facilities and the state’s agricultural history museum — which is still open, but sees scanty attendance, in Tifton.

It approved money for a racing hall and for museums outside metro Atlanta. And in the late 2000s, the state agreed to a $30 million fishing tourism and education program called Go Fish Georgia that was a top priority of Gov. Sonny Perdue.

The agriculture museum, which opened as the Agrirama more than 40 years ago, survived after being taken over by Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College. The move meant it was no longer a line item in the state budget, disappearing from the view of lawmakers. School officials said the state last year spent about $700,000 to help run the facility, which had 11,000 general admission visitors (45,000 when including conference and workshop attendees).

The Go Fish Education Center, which opened at a time when legislators were cutting deeply into the budget, has also remained open off a quiet highway near the state fairgrounds in Perdue's home county. The state spent about $960,000 to run it last year.

Perdue vetoed continued funding in 2007 for Augusta's Golf Hall of Fame, which The Atlanta Journal-Constitution reported never actually included a hall building despite about $7 million in state funding over the years, including money to construct one. While the Augusta facility closed, the Marietta-based Georgia State Golf Association still inducts members into the Georgia Golf Hall of Fame.

By the time the Great Recession started hammering state budgets, lawmakers said they had trouble justifying funding for the remaining halls and museums.

“They were costing us too much money,” Harbin said. “In order to keep them open we were having to take from someone else, whether it was education, public safety or public health.”

The 43,000-square-foot Music Hall of Fame in Macon closed in 2011, and Mercer University bought the property the next year.

While the hall continued to hand out awards, the bulk of its collection was packed off to the University of Georgia. A few paintings hang at the Georgia Sports Hall of Fame.

The 42,000-square-foot Sports Hall sits across from the Tubman Museum in Macon.

Jim McLendon, the executive director of the facility, said the loss of state funding during the recession amounted to a $1 million annual hit to the facility’s bottom line.

“Had it not been for a group of local business people getting together, this place would have closed in short order,” McLendon said.

He said students — often middle schoolers — are bused in for tours of the hall and Tubman Museum some days. The hall had just under 20,000 visitors last year. The space was also rented out about 160 times for events such as small birthday parties, continuing education classes and seminars.

“We are very affordable because we want to drive the revenue and we need to remind people we are still open,” he said.

The hall inducts new members every year — the 2019 class features high school football coach Thomas S. “T” McFerrin, Georgia Tech and NFL wide receiver Calvin Johnson, former Tech and Atlanta Braves slugger Mark Teixeira, track star Brenda Cliette Thomas and announcer Ernie Johnson Jr.

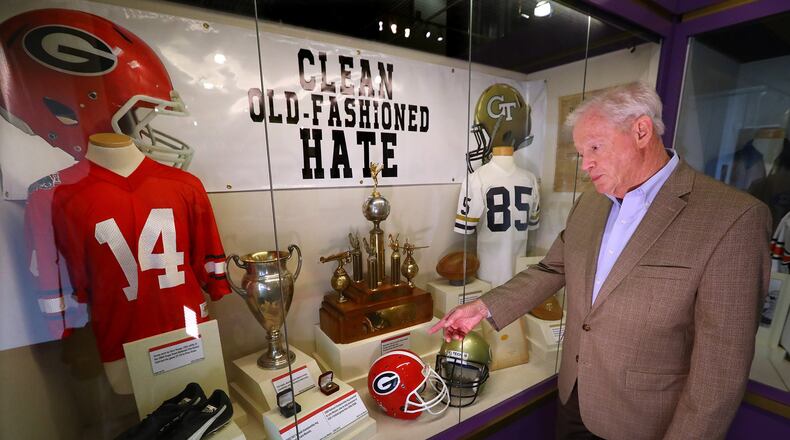

It includes displays — uniforms, gloves, shoes, medals — that tell the stories of the inductees, and of many others, such as boxing legend Sugar Ray Robinson, who was born in Georgia, and Falcons and Atlanta United owner Arthur Blank. There are areas for Georgia college and pro teams, the Olympics, and several sports, including racing and golf. The displays are changed out periodically.

The hall has a mini-basketball court and a NASCAR car display where kids can test their driving skills.

What the hall doesn’t have, McLendon said, is a lot of money to fix what breaks in the building or to update things.

“Most of the technology is 20 years old,” he said.

The hall put together a $597,000 budget for the upcoming fiscal year — which begins July 1 — and about half of it comes from local hotel-motel taxes and a grant from the Macon-Bibb County government. McLendon expects to lose the $85,000 grant for the upcoming year. Only $9,000 is expected to come from ticket sales.

“We are in the black,” he said, “but only barely.”

It is run by two full-time employees, some part-timers and college students.

Steve Anthony, the head of the Sports Hall of Fame's foundation, was an aide to then-House Speaker Tom Murphy when a lot of the hall funding was approved in the 1990s. He said supporters sold the idea of state aid this year as a way to support economic development outside metro Atlanta. Macon isn't rural, but it isn't Atlanta, and the General Assembly has been on a run of backing anything described as helping the economies of rural Georgia ever since current House Speaker David Ralston, R-Blue Ridge, made it his top priority a few years ago.

Anthony described the state grant as “a little money to keep us going.”

Harbin, the former lawmaker, says that without a major influx of taxpayer money, he doesn’t see a bright future for a hall that operates outside a major metropolitan area and sells few tickets. He said legislators during the Great Recession came to the conclusion that “no business would make a decision to stay in business the way this operates.”

But McLendon said the hall is an anchor for a downtown that has seen a resurgence of late. “It’s been proven many times over that the success of a downtown really dictates the success of a community,” he said, and locals aren’t ready to give up on the hall.

“Georgia has a very rich spots history,” he said. “We think it’s important to keep that legacy alive.”

Stay on top of what’s happening in Georgia government and politics at www.ajc.com/politics.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured