As the coronavirus ravaged nursing homes across the country this spring, federal regulators directed Georgia and other states to conduct targeted infection-control inspections of every facility by July 31.

But Georgia is one of the slowest to respond to the directive from The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). The latest CMS data shows that as of July 3, Georgia had completed 41 percent of the on-site inspections, even as more than 1,300 residents of long-term care facilities have died from COVID-19.

Only two other states having a lower completion rate. Many states have already completed all infection-control inspections, with the national average at 88 percent.

The Georgia Department of Community Health, which oversees the state’s nursing home inspection program, insists it will meet the deadline, saying the agency had completed 235 focused infection-control surveys through Wednesday.

“Based on current projections, the surveys should be completed timely,” according to a statement by the agency.

But Georgia’s lagging inspection rate is part of a broader problem with its oversight of nursing homes that has plagued the state for years. DCH’s nursing home inspection unit has suffered from chronic understaffing that has slowed its ability to conduct regular oversight and inspections of nursing homes that care for more than 30,000 sick or frail Georgians.

Currently the unit, which has 33 surveyors on staff, has 23 additional positions that are vacant. This vacancy rate has taken a crippling toll on the Healthcare Facility Regulation Division’s ability to conduct routine surveys, which are the backbone of the oversight program.

Before the coronavirus, Georgia ranked low among its peer states in the southeast region for conducting inspections on time. Federal records show that more than 63 percent of the state’s 358 nursing homes have not received an annual survey in the past 12 months. Some have gone much longer. Roughly a third of the homes — a 119 total — had not received a re-certification survey in the past 18 months, federal data show.

South Carolina is the next closest state in the region, with only 3.2 percent of homes going that long without a re-certification survey.

Tony Marshall, president of the Georgia Health Care Association, which represents most nursing homes across Georgia, said he doesn’t see inspection frequency determing the quality of care. He said annual surveys are unannounced and thus his members must be ready and on their toes to face an inspector’s scrutiny at anytime.

“It’s unfortunate that the default position of people is that if you’re not being regulated you’re not providing good care,” Marshall said. “The satisfaction surveys of our residents and family members indicate otherwise.”

He added that DCH has been very active with his members during the pandemic, checking in on a daily basis by phone to keep tabs on what was happening in their facilities.

The agency switched to remote reviews of infection control early in the pandemic because of a shortage of personal protective equipment. It began more aggressively scheduling the on-site inspections in June, after CMS —which pays states to survey the homes — ordered them them to be completed by July 31 or risk of losing funding.

Persistent problem

Infection-control violations at nursing homes have been a widespread problem well before the coronavirus took hold. A GAO report issued in May found that infection-control deficiencies are consistently among the top violations that inspectors find when they go into nursing homes, but it also found that states undercite the violations. The report found that 64 of Georgia's nursing homes had been cited for infection prevention and control deficiencies in 2017. For a five-year period, from 2013 to 2017, there were 30 homes in Georgia with multiple citations for this problem.

Yet, the recent spate of inspections across the country during the coronavirus hasn’t yielded many violations, according to Toby Edelman, senior policy attorney with the Center for Medicare Advocacy, a non-profit group.

Her group analyzed the inspection data from across the country since the coronavirus shifted oversight efforts this spring to focus on infection control. That analysis found approximately 3 percent of the targeted inspections identified violations during a crisis that has led to some 50,000 deaths in nursing homes and other long-term care facilities.

That’s not plausible, especially when infection control deficiencies were common before the coronavirus outbreak, the group reported. Even when violations are cited they are usually rated as causing no harm.

“We know there are real problems in nursing homes,” she said. “People aren’t getting the care. Really terrible things are going on, and yet the deficiencies that’s been the number one deficiency is all of a sudden not there. It doesn’t make sense to me.”

Too many of the surveys have been short and cursory without enough time to actually uncover violations, said Richard Mollott, executive director of The Long Term Care Community Coalition. He said advocates are concerned because since March, general oversight in nursing homes has been on hold because of the virus. He said infection prevention rules themselves are good, but it’s the enforcement that’s lacking.

“We clearly need vigorous enforcement,” he said. “This whole pandemic and the way it’s played out shows we need to do better…The stories are horrifying.”

DCH said it has increased on-site survey volume since CMS issued its guidance. So far, 10 Georgia nursing homes have had violations during the infection control survey process.

“The Department is working diligently to meet the federal requirements,” the agency said in a statement. “The process is going well.”

Rep. Sharon Cooper, R-Marietta, who chairs the House Health and Human Services Committee, said some on her committee have suggested a review of DCH’s performance during the pandemic.

“Not to be punitive but to make any positive changes that we can to make sure the patients that live in these facilities have the best care during this crisis and any future crisis,” she said.

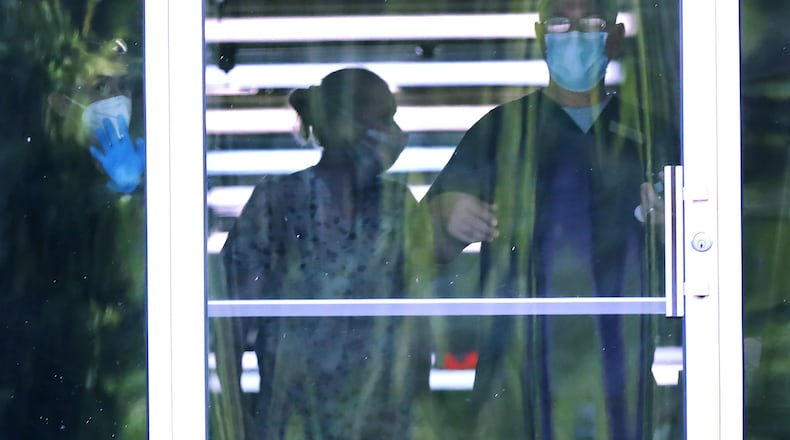

Meanwhile, many families have still been unable to visit their loved ones in nursing homes and see how they’re being cared for and protected. The state’s long term care ombudsman representatives have not been able to access the homes, either. They serve as consumer advocates for residents and hope to resume in-person visits sometime later this summer or early fall, said Melanie McNeil, the state’s lead ombudsman.

“I do suspect once we go back in we’re going to be flooded with complaints,” she said. “I expect when we go back into facilities we’re going to find facilities in worse shape.”

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured