Two months before Election Day, a judge asked state officials a deceptively straightforward question: How had they repaired a data breach in Georgia’s voter-registration system?

They didn’t know.

This exchange, cited in court filings last week, underscored the ambiguities surrounding Georgia's unusually close Nov. 6 election. A series of lawsuits exposed significant failings in how the state managed this year's voting, while also casting doubt on the integrity of future elections.

One judge found that “repeated inaccuracies” in registration data kept qualified voters from casting ballots. Witnesses described chaotic scenes at polling places, where voting supervisors inconsistently applied rules on provisional balloting and other matters. And the plaintiffs in one case claimed that election officials did nothing to protect against “known vulnerabilities,” such as the data breach discovered in 2017, that left their computer system open to manipulation and attack.

The Georgia secretary of state’s office, which oversees elections, did not respond to a request for comment. Attorneys for state and county election officials declined to discuss the lawsuits. In court documents, they disputed the severity and pervasiveness of problems that had emerged since Election Day.

MORE: Abrams preps lawsuit alleging systemic election problems

MORE: ‘We’re moving on’ — Kemp vows to unite Georgia

Elections have never been flawless enterprises. Eighteen years ago, hanging chads – scraps of paper clinging to punch cards – threw a presidential race into turmoil. Every election generates complaints of computer malfunctions, balky voting machines, or human error.

But this year Georgia experienced its tightest race for governor in 52 years, and lawsuits concerning the election fueled questions about whether widespread irregularities tainted the results.

Democrat Stacey Abrams, who ended her campaign Friday but pointedly refused to concede to Republican Brian Kemp, did little to dispel the doubts. “Democracy failed Georgia,” she said in a televised address, accusing Kemp of engaging in misconduct by simultaneously running for governor and supervising the election as secretary of state.

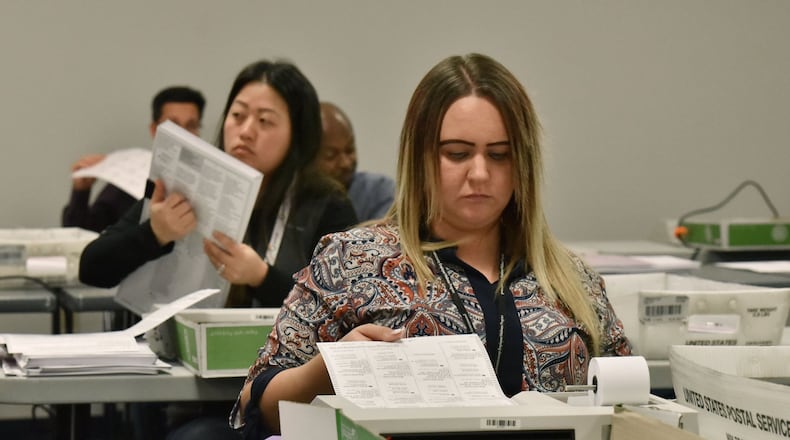

Credit: Alyssa Pointer

Credit: Alyssa Pointer

Abrams spoke of “truly appalling” efforts to suppress voting, of “incompetence and mismanagement” by Kemp’s office, even of “good and evil” forces that tilted the election’s outcome.

She announced that she created an organization called Fair Fight Georgia, which will file a federal lawsuit alleging “gross mismanagement of this election,” in an attempt to de-legitimize Kemp’s win.

Minutes later, Kemp tweeted that “the election is over.”

“We can no longer dwell on the divisive politics of the past,” he wrote.

Not since 1946, when three men laid claim to the governor's office following Gov.-elect Eugene Talmadge's death, has a Georgia gubernatorial election ended so acrimoniously.

“It may well be that there have been problems like this in Georgia’s election system for years and years,” said Laughlin McDonald, special counsel in Atlanta for the ACLU’s Voting Rights Project. “But when you have such a close election like this governor’s race, the issues become much more important and, as we’ve seen, magnified.”

The disputed results also bring to mind the 2000 presidential campaign, which remained unsettled for more than a month after Election Day as Florida officials recounted disputed ballots. The U.S. Supreme Court finally put a stop to the recount, effectively selecting George W. Bush as president over Al Gore.

“It feels like the same level of intensity of Bush v. Gore, although the stakes aren’t as high and that was a Florida battle,” Lee Parks, an Atlanta lawyer and voting rights expert, said Wednesday. “Still, it’s an eerie parallel. I’ve never seen anything quite like this in Georgia.”

It could be just a prologue, though. With the winning Republican barely cracking 50 percent of 3.9 million votes cast, Georgia seems all but certain to become a battleground state in the 2020 presidential race. Another hard-fought campaign will present yet another test for the state’s election infrastructure.

‘Heads in the sand’

The lawsuits began even before the voting ended.

Some cases challenged the grounds for which absentee ballots were disallowed. One sought more lenient standards for determining the validity of provisional ballots, used when questions arise over a voter’s eligibility. Another, filed on Election Day, took direct aim at Kemp, seeking to disqualify him from certifying the results of his own race. That case became moot two days after the election, however, when Kemp claimed victory and resigned as secretary of state.

Lawyers have used statistical analyses, sworn statements and other evidence to document what they say are far-reaching problems and inconsistencies before and after Election Day. What was unusual about their approach was the timing: in past elections, legal challenges typically came only after final results were certified. But the recent cases, brought while votes were still being counted, essentially turned federal judges into quasi-election administrators who took local and state officials to task for not following proper procedures.

In one case, U.S. District Judge Leigh May found that Gwinnett County violated the Civil Rights Act by rejecting absentee ballots from more than 300 voters. May said Gwinnett should not have invalidated ballots only because voters had omitted or incorrectly noted their date of birth. She pointed out that at least three Georgia counties don't require that information at all on absentee ballots.

“This current statewide discrepancy regarding absentee ballots could not only lead to future voter confusion, but also to inconsistency in how such ballots are counted,” U.S. District Judge Steve C. Jones wrote in a separate ruling. Jones expanded on May’s order by directing a statewide count of invalidated absentee ballots.

In another case, the advocacy group Common Cause of Georgia presented evidence that many voters went to the polls on Election Day – some to locations where they had voted for years – only to be told they were not even registered. In at least one instance, according to court filings, poll workers told a dedicated, long-time voter they had no record of his having ever cast a ballot in any election.

“Repeated inaccuracies were identified in the voter registration system,” U.S. District Judge Amy Totenberg wrote as she ordered the reconsideration of provisional ballots.

In September, in a separate case, Totenberg grilled state officials over a breach of voter registration information housed on computers at Kennesaw State University. The officials could not tell the judge what they had done to address the exposure of "data, software, passwords or other critical information," as Totenberg later wrote.

In that case, Totenberg declined to prohibit the use of Georgia's outdated electronic voting machines, which run off the hacked election system. Switching to paper ballots so late in the campaign would create chaos, she said. But she wrote that state officials had "buried their heads in the sand" about the system's vulnerabilities and said she would decide the larger question after the election.

Then, last week, Totenberg detailed instances of mismanagement by county election officers.

In Lowndes County, for instance, poll workers closed the doors to one precinct even though 30 to 40 voters were still in line. They should have been allowed to cast provisional ballots.

A DeKalb County poll supervisor told a woman she would have to vote in Cobb County, where she had previously lived. The woman had neither a car nor a ride to her old precinct. So the supervisor said she could vote “the old-fashioned way” – by provisional ballot. But state law doesn’t allow such ballots to be cast outside a voter’s county of registration. The woman’s vote did not count.

Fulton County, according to Totenberg’s order, gave each precinct only 50 provisional ballots on Election Day. Poll workers weren’t allowed to print extras; additional ballots had to be hand-delivered from the county election office downtown. But the county office sent out just five to 10 ballots at a time. At least two precincts ran out of provisional ballots altogether.

‘Turmoil’

Many Georgians anticipated problems with this year’s election.

More than two-fifths of likely voters surveyed in late October by The Atlanta Journal-Constitution and Channel 2 Action News said it was likely or very likely that someone would tamper with Georgia's voting system. Similar numbers of respondents expected ineligible people to cast ballots, eligible voters to be improperly turned away from the polls or that not all votes would be counted.

But what is still unknown, and may be unknowable, is how much difference any irregularities made.

Not much, according to lawyers for the state and county election boards. They said in court filings that the legal challenges had merely tried to delay the inevitable: certification of the vote totals. And political operatives pointed out that the judges who found problems in the voting were all appointees of former President Barack Obama, a Democrat.

In one filing, the lawyers said the Democratic Party of Georgia “systematically manufactured the provisional and absentee ballot ‘crisis’ … in an attempt to circumvent the election contest procedure in Georgia.”

Abrams gave no details on the federal lawsuit her new organization plans to file over her lost election. But any further challenges, lawyers for the state and counties contended, would create “unnecessary turmoil.”

In a ruling before Abrams bowed out, Judge May said election officials missed the point.

“The harm alleged (by the plaintiffs) is disenfranchisement, regardless of the outcome of the election,” she wrote. “It is of no consequence to this court who wins the elections; what matters is who is entitled to exercise their constitutional right to vote and have that vote counted.”

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured