A lawsuit alleging widespread voting problems in Georgia is pursuing an ambitious solution: restoration of the Voting Rights Act and federal oversight of elections.

After notching an initial court victory last month, allies of Stacey Abrams will now attempt to prove through their lawsuit that Georgia's election was so flawed that it prevented thousands of voters from being counted, especially African Americans.

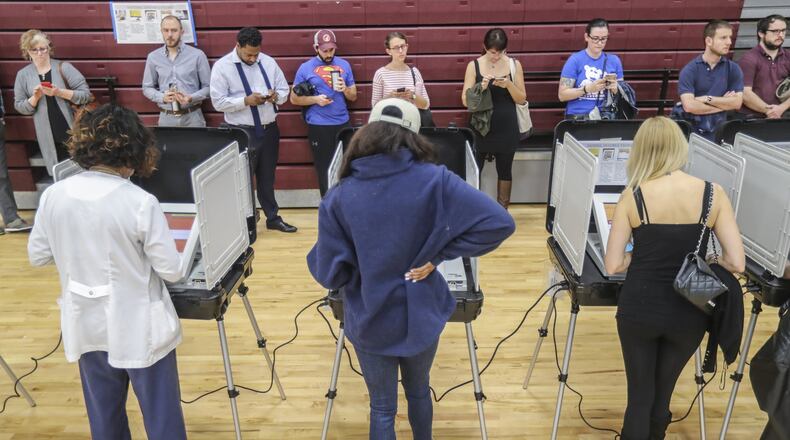

The lawsuit links civil rights and voting rights with the aim of showing that elections are unfair in Georgia because racial minorities suffered most from voter registration cancellations, precinct closures, long lines, malfunctioning voting equipment and disqualified ballots. More than 50,000 phone calls poured into a hotline set up by the Democratic Party of Georgia to report hurdles voters faced at the polls.

If successful, the case has the potential to regain voting protections that were lost because of the U.S. Supreme Court's 2013 ruling in a case involving the Voting Rights Act, the landmark legislation approved in 1965. The court decided that several states with a history of discriminatory practices, including Georgia, no longer had to obtain federal clearance before making changes to elections.

Bringing Georgia back under the Voting Rights Act will be tough because the lawsuit would have to prove intentional discrimination in the state’s election laws and practices. But the plaintiffs see an opportunity to try to make that case.

Free from federal supervision, voter suppression has been on the rise in Georgia, said Allegra Lawrence-Hardy, an attorney for the plaintiffs, which include Fair Fight Action, an advocacy group founded by Abrams, along with Ebenezer Baptist Church and other churches.

“This is modern-day Jim Crow,” Lawrence-Hardy said. “Minority voters simply have a harder time voting and having their vote counted in the state of Georgia than other voters. That’s just factual, and that’s part of the information we’ll be submitting to the court.”

Georgia election officials say that’s not, in fact, “factual.”

They reject the idea that election laws and policies target minorities or infringe on voting rights, according to their filings in federal court.

Many of the alleged voting obstacles in November’s election resulted from decisions made by local election officials — not by any statewide effort to disenfranchise voters — wrote defense attorneys for Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger. His office and his attorneys declined to comment.

The lawsuit “attempts to string together a variety of isolated incidents to weave a new theory: that a variety of independent and unrelated actions by mostly local officials somehow resulted in constitutional violations that require massive judicial intervention,” a March 5 defense brief states. “Indeed, plaintiffs claim that Georgia’s election system is so flawed that the only solution is to place the entire state in federal receivership.”

U.S. District Judge Steve Jones ruled against the state government's motion to dismiss the lawsuit May 30, allowing the case to move forward.

Already, the plaintiffs have collected testimony from more than 200 people who reported difficulties voting. They reported that voter registration records disappeared, provisional ballots were incorrectly issued to legitimate voters, hours-long lines discouraged turnout and voting machines flipped votes from Abrams to Brian Kemp, who won the governor's race by nearly 55,000 votes, a 1.4 percentage point margin of victory.

To try to show voting rights were violated, the plaintiffs will seek emails, documents and depositions from Georgia election officials.

No states are currently subject to federal review of elections under the Voting Rights Act, and only one city falls under that provision of the law: Pasadena, Texas, which settled a lawsuit filed by Hispanic voters alleging that their voting strength was diluted by redrawn voting districts.

Before the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2013 Voting Rights Act decision in Shelby v. Holder, nine states were subject to federal oversight, including Georgia. Most of the states covered by the Voting Rights Act were in the South and West.

“This could turn out to be a case of national legal importance, but it’s too early to say,” said Rick Hasen, a law professor at the University of California, Irvine, who specializes in election law. “The complaint presents a general picture about the kinds of hurdles African American voters and other voters faced. It’s trying to show how all these things accumulate to a voting rights violation, even if any one in isolation might not.”

A judge could also order incremental changes to Georgia elections instead of making the state subject to federal clearance under the Voting Rights Act, said Lori Ringhand, a constitutional law professor at the University of Georgia.

“Depending on what the evidence shows, the judge would have a fair amount of discretion to decide how wide of a remedial system he would want to put in place,” Ringhand said.

Though the election for governor is over, the lawsuit continues the fight for voting rights that invigorated last year’s election, said the Rev. Raphael Warnock, the senior pastor for Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, where the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. preached during the civil rights movement.

Georgia’s election laws continue to harm African Americans, just as they did decades ago, Warnock said.

For example, a Georgia election policy called "exact match" prevented more than 53,000 people from being added to the state's list of active voters last year because of discrepancies in their registration information, such as a missing hyphen in their name. About 80% of those potential voters were African Americans, Latinos or Asian Americans.

In addition, Georgia's "use it or lose it" law allows election officials to cancel voters' registrations if they don't participate in elections for several years, a practice that critics say disproportionately affects minorities. More than 1.4 million registrations were canceled from 2012 to 2018 when Kemp was secretary of state because they stopped participating in elections, died, moved away or were convicted of felonies.

Warnock said these kinds of voting hurdles are more sophisticated versions of “tricks they played in the darkest era of the South” to prevent African Americans from voting, such as literacy tests and poll taxes.

“The efforts to keep ordinary people from voting find ways to reinvent themselves at every junction,” Warnock said. “All of these tactics really hearken back to the very era that the civil rights movement emerged to address.”

Some of the obstacles voters faced in November were caused by one-time problems rather than broad deficiencies in the voting system, said Deidre Holden, the elections supervisor for Paulding County, located west of Atlanta.

Record turnout led to long lines. Voter registrations were canceled when Georgians moved to a new county and forgot to re-register. Old voting equipment broke down.

“There were some good complaints, and some were blown out of proportion,” Holden said. “Complaints needed to be heard. I don’t think anyone should be disenfranchised from voting. No one should ever be turned away.”

Without the protections of the Voting Rights Act, Georgia and other states have increasingly passed laws to remove voters from the rolls and limit new registrations, said Leigh Chapman, the director of the voting rights program for The Leadership Conference Education Fund, which focuses on elections, education and criminal justice issues.

“Georgia has been at the epicenter of the problem — a full-on assault on the right to vote,” Chapman said. “Until Congress restores the Voting Rights Act, it’s critical that organizations bring these lawsuits to protect individuals’ rights to vote.”

A bill introduced in the U.S. House of Representatives in February would create a process to determine which states with a history of voting rights violations must receive approval from the U.S. Department of Justice before making changes to election laws. The bill is pending in a subcommittee.

Georgia elected officials, including Kemp, have said voting has never been easier.

A record 7 million Georgians were registered to vote for November's election, when turnout reached an all-time high for a midterm.

In addition, the General Assembly passed a bill this year that changes many of the election laws criticized by the lawsuit. The new law replaces the state's voting machines, requires printed-out paper ballots, delays registration cancellations and prevents precinct closures within 60 days of an election.

The lawsuit contends that the legislation doesn’t go far enough or address many of the difficulties voters reported on Election Day.

Jones ruled that the bill didn’t address poll worker training of ballot handling, inappropriate cancellations of voter registrations and allegations that the state’s “exact match” policy disproportionately impacts minority voters.

BALANCED COVERAGE

The debate over Georgia’s voting system is divisive, and these types of stories receive special treatment. We always try to present as much information as possible so that readers can use those facts to reach their own conclusions. To do that, we rely on a variety of sources that represent multiple points of view. Today’s story includes comments from the attorney for the plaintiffs suing the state and a constitution law professor from the University of Georgia.

BEHIND THE NUMBERS

1.4

Percentage margin of victory for Bian Kemp in the race for governor

1.4

Million registrations that were canceled from 2012 to 2018 in Georgia

7

Million Georgians who were registered to vote for November’s election, when turnout reached an all-time high for a midterm.

200

Testimony plaintiffs collected from people who reported difficulties voting

55,000

Brian Kemp’s edge in votes to win the governor’s race

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured