Scientists sent people to the moon. Can they reinvent the toilet?

When people ask Georgia Tech engineering professor Ilan Stern about his latest high-tech project, he talks about developing systems for combustion engines, viscous heaters and automatic high-pressure steam valve systems.

“They say, `what are you building, a rocket?’” Stern said.

He’s actually part of a world-wide team of Georgia Tech-led engineers, chemists and biologists trying to design a cheap, self-contained toilet not dependent on a sewer connection.

It is among the most-ambitious attempts yet to treat sewage from 2.5 billion people in developing nations that is currently piped into ditches or streams or left in fields. The excrement spreads parasites and diseases such as cholera, which kill half a million children a year. Millions more adults and children are sickened from waterborne diseases spread by untreated sewage.

Billionaire Microsoft founder Bill Gates challenged top universities and businesses in 2011 to solve the problem - and offered $200 million in funding. Since then engineers from Caltech to the University of KwaZulu Natal in South Africa, along with appliance makers such as Kohler, have developed dozens of prototypes. They include sewage treatment stations on trucks to stand-alone toilets that pack a treatment system in the tank, turning human waste into sanitary material that can be burned, thrown away or used for fertilizer.

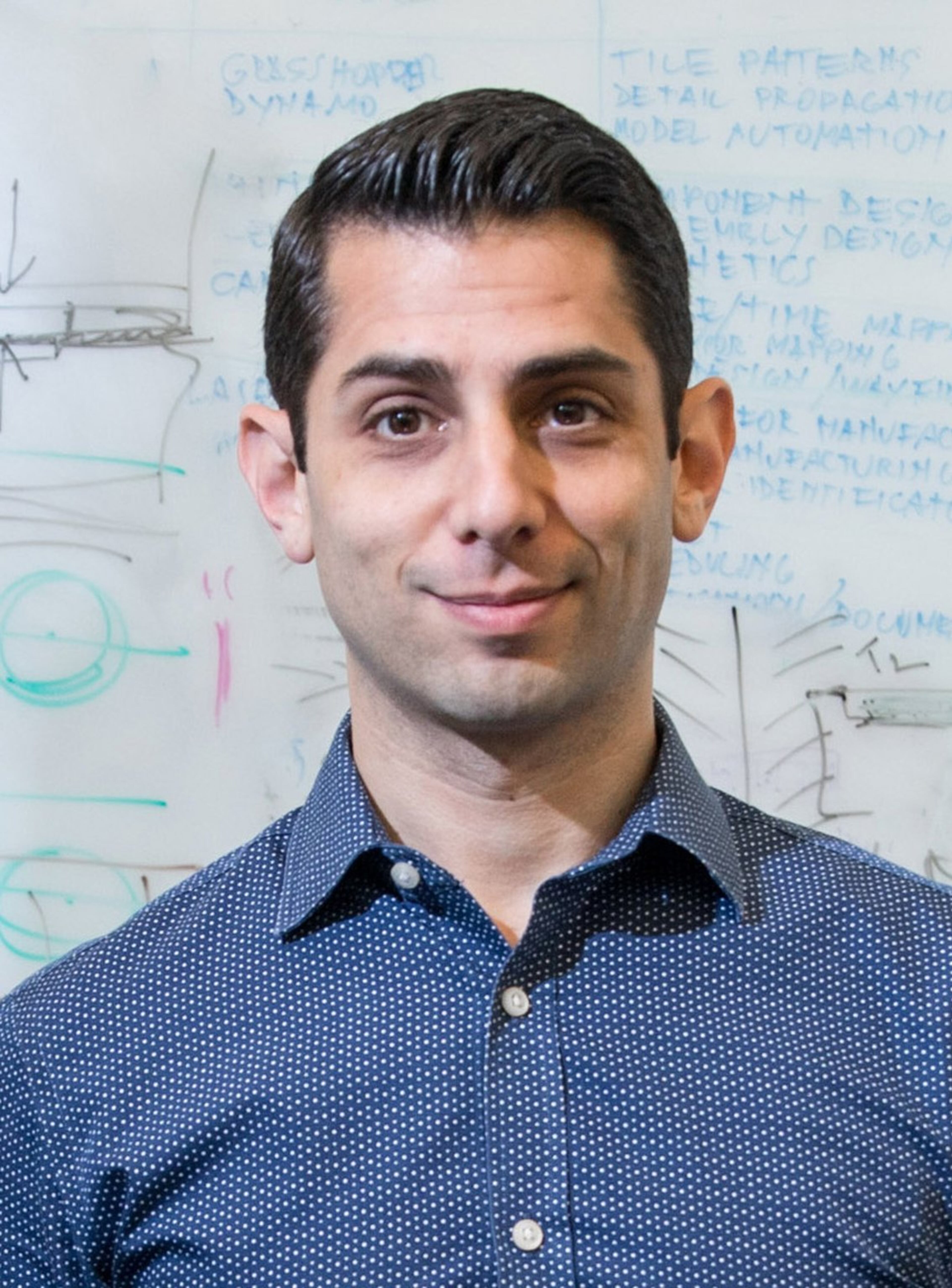

In May, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation selected Shannon Yee, an associate professor at Georgia Tech, to lead the final push. Yee and his globe-trotting team have been given a $13.5 million budget and 39 months to sort through the prototypes and remaining challenges.

“When people started working on this, there was a realization that wow, this is a lot harder than we thought,” said the 34-year-old Yee, who has graduate degrees in mechanical and nuclear engineering.

Think of any U.S. sewage treatment plant. It is spread across multiple acres with hundreds of millions of dollars of equipment. Bill Gates’s john must do what a plant does in a three-foot-by-three-foot space, operate for five cents per user per day using little or no water, not be smelly, and cost a family no more than $450 to purchase.

“To reduce something to that scale is an incredible engineering challenge,” said Brian Stoner, a Duke University engineer also working on the project.

A billionaire’s interest

The modern loo has worked on the same principal since its 1775 patent in England, which required using water to flush waste through pipes into a nearby stream or cesspool. It used an S-shaped water trap to seal the pipe so noxious sewer gases wouldn’t rise into the home.

The next big step in sanitation came when cities connected home systems to community water and sewer systems. Cities between 1900 and 1940 began treating drinking water going into homes and the sewage exiting it, killing most pathogens. That innovation created the most rapid health improvements in U.S. history, according to a 2005 Harvard University study. Typhoid and other diseases disappeared, lowering infant mortality by three-quarters, child mortality by two-thirds and all urban deaths by about 15%, the study estimates.

But Western-standard sanitary water and sewer systems cost billions of dollars, which developing countries can’t afford. They are also impractical because of the disruption it would cause in cities that have grown helter-skelter, and many cities in developing countries have constrained water supplies.

Enter the Gateses. The family began adopting world health issues into their philanthropic portfolio in 1998, from expanding the delivery of vaccinations to promoting family planning. It floated the Reinvent the Toilet Challenge eight years ago to create an off-the-grid solution.

“It was seen as a poor country’s problem, so there was no market driver,” said Brian Arbogast, who oversees sanitation projects at the Gates Foundation.

Gates is proud of what his money has produced so far.

“I even drank water made from human feces a couple years ago,” he chirped in his blog last November.

Arbogast said there are two key challenges still unsolved. One is for Yee’s team to perfect the many ideas into one that will work so well and look so good that people will want them in their homes. The second is doing that at the prescribed cost of $450 or less.

Turning sewage into dollars

Yee’s team — at 54 members and growing — comes from universities and businesses spread from here to England, Switzerland and South Africa. It is made up of some of the original members who participated as well as some he selected, and others may be added to bring in new expertise.

They’re not starting empty-handed, thanks to the work of previous teams. One prototype uses solar power to generate complex electro-chemical reactions to sterilize waste. Another creates a virtuous cycle from feces. Raising and lowering the lid mechanically powers a process inside the unit that turns solids into dried pellets, which are burned in a combustion chamber. The heat dries recently added sludge and helps power the distillation system that turns liquids into water that can be used in the garden. Another toilet model used sewer gases to create energy to charge cell phones, which are more ubiquitous than toilets in some developing countries.

But there also have been plenty of glitches over the years. One model cleaned and recycled urine and water to be used for other flushes or hand washing. Though the graywater, as the recycled water is called, was clean enough for washing, it was not crystal clear and the people using the prototype balked.

“You can build this amazing piece of technology that does everything you want it to do, but if it’s not accepted by the community, you’ve failed,” said Georgia Tech’s Stern.

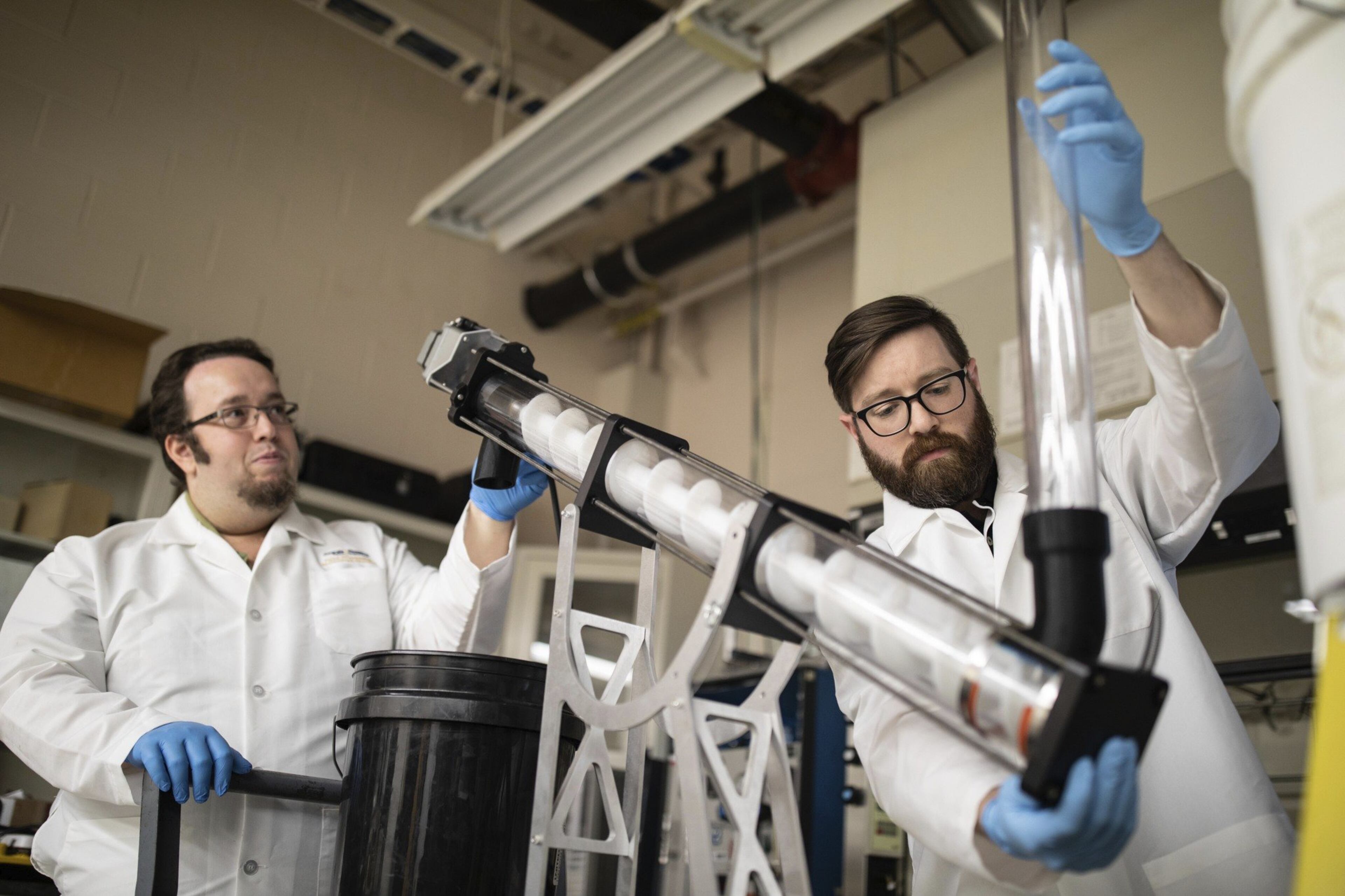

Another problem rose from researchers’ desire, for obvious reasons, to avoid using “the real stuff” when testing prototypes.

Simulated feces with names such as “Simulated Sludge Recipe Number 9” were the go-to poo for a while. But they lacked key properties of unsimulated sludge, also known as original recipe No. 2, that threw off the functioning of some prototypes in the field.

“The real stuff is a fairly complex material in its traditional form,” said Duke’s Stoner.

And while prototypes have shown remarkably creative engineering and chemistry, some of them cost $30,000 or $40,000 to make.

Then, there are as many cultural barriers to solve as physical ones. Societies have developed a multitude of taboos and expectations about bodily functions, from sitting or squatting to when and where it’s appropriate.

Many of those taboos fall on women. Many societies allow a man to relieve himself anytime and openly in fields, for instance, while women often must seek seclusion or wait until nightfall. Having an in-home toilet will solve many problems for them, Stoner said.

Four months into the project, Yee and his colleagues are in the early stages of sorting through the best ideas for processing the sludge. They have about eight months to select, redesign and perfect one or two of those “back-end” systems.

Then they have 18 months to build and field test prototypes, which will include cultural preferences such as installing a pedestal commode or a squat plate. Then they’ll have about another year to flush out any bugs and finish the final designs. It’s a difficult challenge on a tight deadline.

Arbogast said the rights of the designs will belong to those who created them, but there is an agreement to keep royalty payments low so manufacturers can make and sell them as cheaply as possible. The installation and use of the toilets need to be market-driven to succeed.

“The thing that keeps me up at night is will I be able to get commercial interest,” said Yee.

Still, he’s optimistic. Think, he said, of selling 20 million toilets a year. That would give some company a healthy bottom line.

Why it matters:

Untreated sewage dumped in waterways or ditches spreads diseases that kill half a million children a year and sicken millions of adults worldwide.

Completing the Bill Gates-funded project to create a toilet that can be marketed and treat waste without a sewer hookup would lessen human suffering.