From kidnapper to doctor

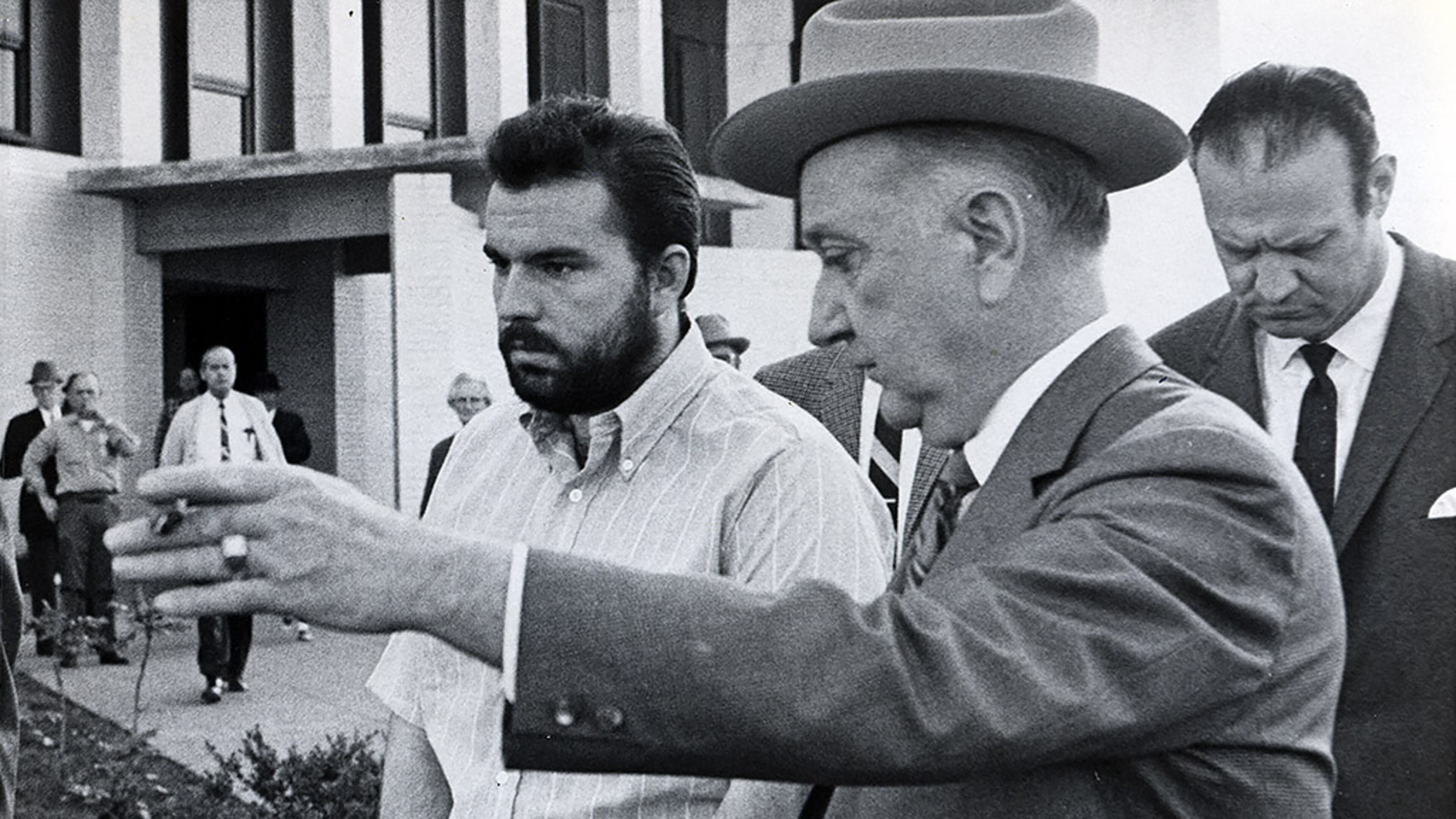

Gary S. Krist got a half-million dollars’ ransom, federal prison time and national infamy when he kidnapped Emory University student Barbara Jane Mackle and buried her alive in a box.

Then he got something else: a medical license.

Nearly 50 years after the infamous crime, many still recall it, especially in Georgia. The case still pops up in news reports, including one in the New York Post this year. Krist’s accomplice was the first woman ever added to the FBI’s 10 Most Wanted list. Two TV movies were made about the case.

Krist's case was examined as part of The Atlanta Journal-Constitution's review of medical board orders for doctors across the country accused of sexual misconduct. While many cases are kept secret, the AJC identified more than 2,400 doctors disciplined since 1999 after allegations of sexual misconduct involving patients.

Most were able to return to practice, the investigation found. That’s because regulators have come to view doctors who sexually abuse patients as “impaired” and now allow even doctors with egregious violations to redeem themselves through treatment programs.

Yet the doctors avoid public condemnation or professional damage because of a glaring lack of information available to patients from the agencies tasked with protecting them.

In Krist's case, the information gap allowed vulnerable patients to see him in a hospital or enter his office, unaware of his criminal history or complaints that he had crossed sexual boundaries with patients.

“When he wants to turn it on, he can charm the birds right out of the trees,” his wife once told a UPI reporter.

From prison to medical degree

Krist, now 71 and residing in Auburn, Ga., was 23 at the time of the kidnapping. He was also a prison escapee with a record of car thefts dating back to his teenage years.

Mackle was an heiress to a Florida real estate developer. Krist spent months researching Mackle’s family and stalking her, working with his girlfriend. He meticulously planned the crime, installing air tubes and a fan in the burial box to pump air from the surface, and including water and food.

Upon burying Mackle, Krist called her father and told him how to dig up a ransom note Krist had buried in the millionaire’s garden. The note said the fan battery would die in seven days. And so would Mackle if the family didn’t pay.

She was trapped underground for 83 hours.

Mackle’s father paid the ransom, and FBI agents swarmed the Gwinnett County woods seeking the location Krist described in a phone call. They eventually unearthed her, physically unharmed.

Krist was caught trying to flee the country. He was tried and sentenced to life in prison, but paroled after just 10 years, in 1979.

Krist wasn’t just any ex-con. He had a plan.

Less than a decade after his release he got a pardon, and he was accepted at Ross University School of Medicine, in the Caribbean. As part of his school work he trained in a Connecticut hospital that didn’t know about his criminal history. But after a fellow worker there recognized him, he left the hospital and set local news media abuzz.

He graduated from Ross in 1993 and headed to the West Virginia School of Medicine in 1994 for a four-year residency in psychiatry at its hospital.

It didn’t last four years. He racked up a disciplinary file for conduct with patients that worsened from rude comments to sexual ones, then sexual contact, according to information disclosed years later in medical board documents.

He told a 13-year-old girl with an eating disorder, “You have a big butt.” To a patient who tested positive for HIV, he said, “Your boyfriend must be thrilled.”

He questioned a patient intrusively about her sex life when she came in for dermatitis, made another uncomfortable with an unchaperoned breast exam when he mentioned her “big boobs,” and gave a third a back rub and massage when she came in for a sore throat. He denied any problems.

Then a patient in 1996 accused him of sexual assault at the motel where she lived, notifying the hospital and the local sheriff’s department as well. Investigations commenced. Gary Krist denied touching her. And then he disappeared.

Another chance, new offenses

He turned up in Georgia. The sheriff’s office in West Virginia never obtained an arrest warrant, so Georgia officers said they couldn’t get a warrant for them for Krist’s DNA and fingerprints. That investigation went away.

Krist took a medical leave from his residency, then abandoned it.

Krist was not a quitter, though. By 1998, he was applying for medical licenses. Alabama said no.

But Indiana considered the Mackle conviction and decided to give Krist another chance. It granted him a license, with probationary restrictions, in 2001.

Its public order, though, mentioned only “his past conviction and denial of licensure in Alabama.” It didn’t reveal details of his criminal past.

The medical board itself was in the dark about the allegations against him in West Virginia. On his license application, Krist denied ever being admonished, censured or reprimanded or being requested to withdraw or resign from any hospital where he trained.

In any case, the conditions Indiana set were too much for Krist. Instead of submitting reports by his practice monitor, he submitted reports he wrote, signed by the monitor. He refused to submit the monitor’s written agreement with him, as required.

In 2003, the Indiana board issued four separate public orders, suspending Krist and initiating procedures that would lead to taking his license back.

Only in the final order of revocation, in October 2003, did it make the long West Virginia disciplinary history public in Indiana, accusing him of lying on his license application.

Back to prison

Krist was arrested again in 2006, charged in Alabama with trying to import 38 pounds of cocaine and four illegal immigrants into the U.S. from Colombia. He went to prison from 2007 to 2010, then was ordered back to prison in 2012 after violating probation by leaving the country without permission. He was last released on July 2, 2015.

Mackle has not given interviews since a Miami Herald reporter wrote a book about her ordeal.

Krist refused to speak with a reporter at his secluded Barrow County home.

At one point around 2005, according to an AJC article, a friend tried to get Doctors Without Borders to take him. They didn’t.

There is no public record of Krist ever practicing medicine again.