Opinion: How contact tracing fights coronavirus’ spread

Before the coronavirus, Bethany Zimpelman was an elementary school nurse, tending to her students’ playground injuries and primary care.

Now she is a public health detective of sorts, following an invisible web of coronavirus infections.

Every time an Alaskan tests positive for the coronavirus, a small army of nurses like Zimpelman leaps into action, launching the virus investigations known as “contact tracing.”

In Alaska, each person with a confirmed positive coronavirus case — about 375 as of early last week – has gone through the contact-tracing process.

Contact tracing involves deciphering the close human contact an infected person has had during their infectious period, creating a detailed timeline of their daily life and identifying and advising the people exposed that they need to self-quarantine or isolate.

It is low-tech, detail-heavy work that involves asking strangers probing questions by phone for hours at a time, and methodically checking back with exposed people to ask about their symptoms.

Alaska public health officials say it’s one of the best weapons they have in corralling the coronavirus.

“Every single person who has tested positive for coronavirus has had this tracing process done,” said Tim Struna, head of the Division of Public Health’s statewide public nursing section. “It is part of what’s keeping the curve down in Alaska.”

As a result, the projected exponential growth in coronavirus cases in Alaska has not materialized, Struna said.

Contact tracing is a core tool in epidemiology, used for everything from identifying tuberculosis clusters to measles outbreaks. Even before the coronavirus pandemic, Alaska’s public health nurses already did a lot of it, perhaps spending a quarter of their time tracking exposures, said Struna.

Now they are spending 70 percent of their time on it.

Here’s how the process works: When an Alaskan tests positive for COVID-19, nurses, including those drafted to help after their schools shut down, pick up the phone.

Usually, a person who tested positive has already been informed of the test result by their medical provider. The next phone call they might receive is from a contact tracer.

Nurses ask questions to build a timeline of the person’s sickness, determining their period of infectiousness – when they are most likely to be shedding the virus in respiratory droplets or other secretions.

Then comes the part that makes contact tracing more like a detective’s investigation: “We ask them to try to recall each and every person they came into contact with during that infectious window, and the nature of the contact, and the duration of the contact,” said Joe McLaughlin, Alaska’s state epidemiologist.

It’s a tall order, said Zimpelman.

“Fourteen days is a long time to remember,” she said, and many people are initially foggy when asked to recount every detail of their day on the spot.

So, nurses are trained in the painstaking process of asking probing questions: On Monday, did you leave your house? Where did you go? How did you get there? Did you travel with anyone there? Did you talk to anyone when you got there? How did you travel home?

Repeat that for every single day, and you’re starting to catalog a comprehensive list of close contacts.

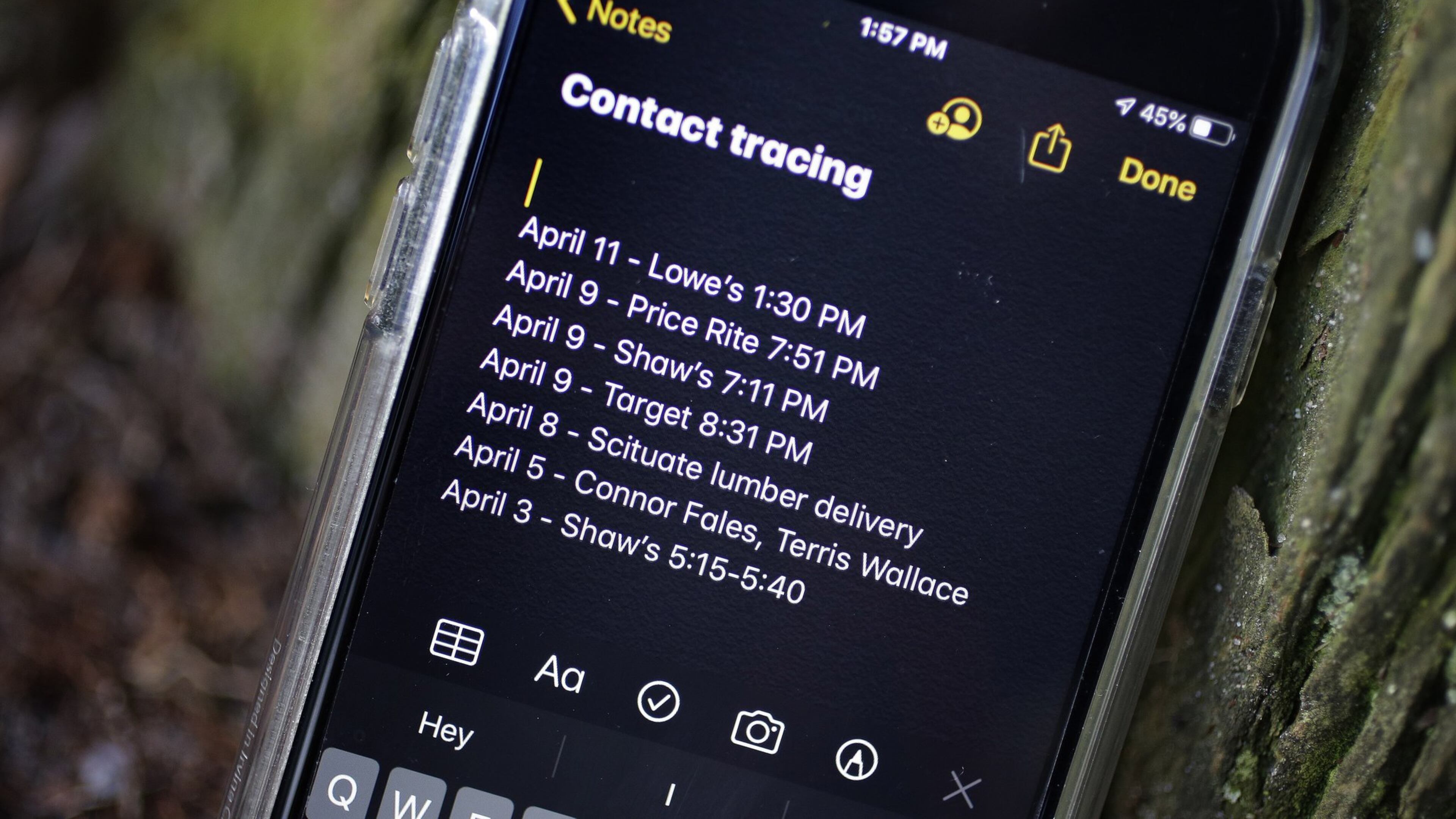

Sometimes nurses ask people to use their phones or calendars to jog their memories about what they’ve been doing — who they’ve been texting, where they’ve been spending money.

“We have people re-track their bank statements, their credit cards. Sometimes moms, especially, will be taking pictures — they have like a little journal on their phone,” Zimpelman said.

With every phone call Zimpelman makes, she learns where the virus may have wandered: to a grocery store, a workplace, a park.

In some cases where exposure within a public place or institution is suspected, other data can be used. Medical offices, for instance, can provide chart information; businesses can share transaction records; airlines could offer passenger manifests.

The conversations can take an hour or more, said Art Tovar, head of the community health nursing program for the Anchorage Health Department.

In general, the quality of the contact tracing information relies on the person’s willingness to volunteer it to a nurse.

Getting an accurate and complete timeline of the infected person’s contacts is crucial to the next step of contact tracing: Letting all of the “close contacts” know they have been exposed to the coronavirus.

If you’re identified as a close contact of a person with coronavirus, your name goes on a list of people being monitored, according to McLaughlin.

Then a nurse calls you, lets you know you’ve been exposed, and tells you to self-quarantine for 14 days and closely watch for virus symptoms, he said.

So far, Zimpelman and the other nurses have made many hundreds of calls to untangle the threads of interaction that could have led to infection — or that could lead the new ones.

And with each call, Alaska comes a little closer to understanding the scope of the coronavirus.

Michelle Theriault Boots writes for The Anchorage Daily News. These three stories are part of the SoJo Exchange of COVID-19 stories from the Solutions Journalism Network, a nonprofit organization dedicated to rigorous reporting about responses to social problems. Today, we examine some steps being taken around the country, which could provide some answers in our fight against the coronavirus.