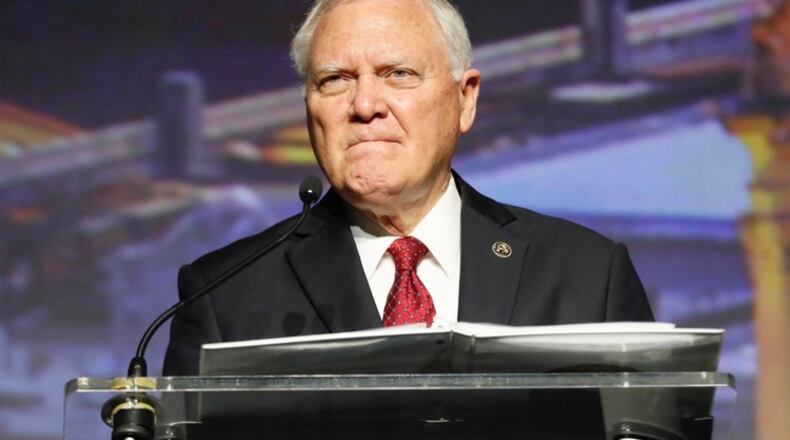

Nathan Deal has embarked on his final year as governor, so he is undertaking some rituals of the office for the final time. Such was the case this past week when he delivered one last State of the State address to legislators.

For Deal, who warns he’s no lame duck but has a modest legislative agenda for this eighth and final year, it was largely a trip down memory lane. Or to adopt his metaphor, a stroll through the “orchards” that bear the fruit of his labors these past seven years.

The crop is bountiful, judging by a new statewide opinion poll conducted for the AJC: Deal’s approval rating hits 53 percent. That handily beats the approval ratings for the Legislature (46 percent), the GOP (39 percent), the president (37 percent) or the Democratic Party (34 percent). Georgians’ satisfaction with their state’s direction is, at 64 percent, far greater than their satisfaction with the nation’s trajectory (41 percent).

We can place his governorship on the scales for a final measurement once it’s over. For now, I asked during a post-speech interview, which issue does Deal think will require the most continued attention after he leaves office?

He didn’t hesitate: “K-12 education always has to be where we still need the most effort exerted, and in some cases the most reforms made.

“And that is very difficult. I found it out the hard way. Sometimes those who are within the institutions that you’re trying to help are the ones who resist that help the most.”

Indeed, education is a perennial worry for Georgians — it’s their largest concern today, again per the AJC poll — and has been the subject of some of Deal’s most bruising political battles. Voters’ resounding rejection of his Opportunity Schools District constitutional amendment in 2016 undermined much of the rest of his second-term agenda for education.

Deal expressed optimism about a Plan B legislators approved last year to address chronically failing schools, but it’s clear he knows those schools — and the students trapped in them — remain Georgia’s biggest obstacle to realizing its potential.

“If we really want to do anything about poverty,” Deal said, “if we really want to do anything about crime, if we really want to do anything about a skilled work force that will continue to attract high-paying jobs, we have to start with basic k-12 education.

“And we cannot allow even those within the education community to offer excuses for why they cannot achieve excellence. We know they can. We have examples of those, in the worst economic circumstances, who have been able with the right approach, with the right leadership, to achieve great things.”

When I asked him to give Georgia’s public schools a grade for progress over his seven years so far, he was blunt about their shortcomings: “Probably a C. We have made progress. But we’ve had to fight many people along the way.”

Deal acknowledged some schools, even some low-performing ones, have made greater strides. But he insisted there remains much work to do — and indicated it may not be within the power of a governor to accomplish it all.

“Until such time as the education community itself comes to the realization that they need to improve the quality of their educational offerings and the quality of the students that they are graduating, only then will you be able to address these bigger and broader issues (such as poverty). And what that requires is … the community as a whole, the parents, those who support our local schools, to demand that they do better.”

About the Author