The Atlanta Zoo was in terrible shape.

Solitary animals paced or sagged glumly in concrete and tile-lined cages. The deaths of several of them in the 1980s brought allegations of animal cruelty, inadequate care and incompetent management. The facility was showing its age and was underfunded.

A Parade magazine article in 1984 blasted the zoo as one of the ten worst in the U.S. and helped bring matters to a head. Then-mayor Andrew Young recruited Georgia Tech professor Terry Maple — an expert in animal behavior and psychology who was internationally known for his expertise in great apes — to take over. The appointment turned around the failing trajectory of the zoo.

Maple created a capable core team, raised money, instituted an expansive rebuild and rebranding program — including the birth of the moniker Zoo Atlanta — established corporate partnerships that helped foot the bills and transformed the zoo into a top-drawer educational and research facility. All that in the space of just a few years.

“He was a dynamic man,” said Gail Eaton, who once served the zoo as vice president of marketing and communications under Maple. “He knew what he wanted and he kept going until he got it.”

Mollie Bloomsmith, a noted animal researcher and a former Georgia Tech psychology student mentored by Maple, echoed that.

“He was a brilliant guy and extremely ambitious, and he had a vision of what was needed to improve animal welfare,” Bloomsmith said.

Credit: AJC

Credit: AJC

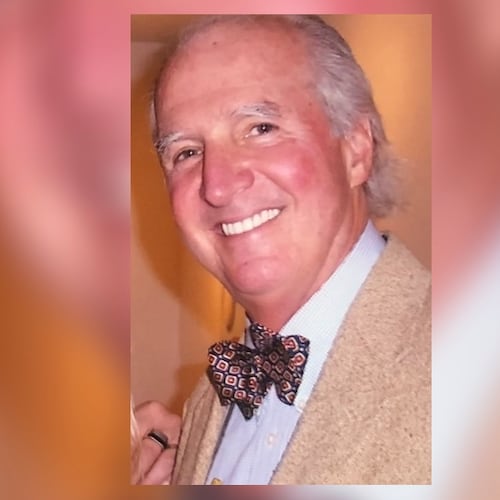

After touching a tremendous number of lives both two- and four-legged, the 77-year-old Maple died Dec. 3 after suffering complications from an infection.

Maple had a winning smile and ready laugh, along with a robust physique that friends would point out reminded them of his sliverback charges. He also had a propensity for sharing a drink and a story, and his charisma could light up a room.

Combining his relentless optimism with canny marketing, he used tools such as the zoo’s best-known resident, gorilla Willie B., and local media to get the community behind his plans.

Maple’s signature projects drew widespread acclaim.

He replaced the empty, barred cages with naturalistic outdoor habitats including trees, grass and natural structures. Animals were brought out of solitary confinement into social groups. They sired more offspring. A heightened emphasis on education captivated visiting school children and their parents.

“I think the best day of my career was everybody who worked together — and Terry crying with happiness — because Willie B. stepped onto grass for the first time since he was three years old,” said Rita McManamon‚ recruited as the zoo’s chief veterinarian. It marked the debut of the Ford African Rain Forest, another public-private partnership with Maple’s stamp on it.

Long and painstaking negotiations with the Chinese culminated with giant pandas Lun Lun and Yang Yang being loaned by the Chinese to the zoo in 1999, a buzzy event across all of Atlanta. At the time it was one of only three zoos in the country exhibiting them.

Friends and family say a bond with animals infused Maple’s childhood, igniting a passion that led to a to a Ph.D in psychobiology at the University of California-Davis and an eventual professorship at Tech.

Maple kept a part-time position with the university while running Zoo Atlanta. He brought Georgia Tech graduate psychology students to Grant Park to study all animals great and small.

“The projects were focused mainly what I’d call animal welfare,” said Bloomsmith, who now heads behavior management programs at the Emory National Primate Research Center. “How can we better take care of animals in a zoo setting?”

The studies ranged from trying to determine whether animals in the petting zoo needed a “retreat space” to how well orangutans could solve problems with a joystick-equipped computer. Maple spread the resulting knowledge far and wide, through a journal he founded. He penned many books.

Exhibiting his passion could take some unusual forms and showed his humor. The veteran scientist was known to show up at scientific conferences wearing a gorilla suit.

“And he made up these — he called them psongs,” said daughter Molly. He would rewrite popular songs into scientific ditties. “Sixteen Candles” became “Sixteen Mandrills.” “I Believe I Can Fly” morphed into “I Believe I’m a Fly.” And he was not shy about bursting into song, or psong, at any moment.

The veteran zoo administrator departed in 2002, returning to Georgia Tech and later helming the Palm Beach Zoo. He left vivid memories behind for those who knew him.

“I’m having trouble imaging a world without Terry Maple,” Eaton said.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured