Judge Willam Bootle, judge who ordered desgregation of UGA, dies at 102

Published Jan. 26, 2005

Federal Judge William Augustus Bootle of Macon made history when he ended 160 years of segregation at the University of Georgia by ordering the admission of two black Atlanta students in 1961.

Bootle, 102, died at his Macon residence Tuesday. He suffered from heart problems.

During the 1960s, Bootle made a string of historic civil rights decisions, from desegregating the state’s college system to integrating buses and school systems to ensuring blacks’ place on voter rolls.

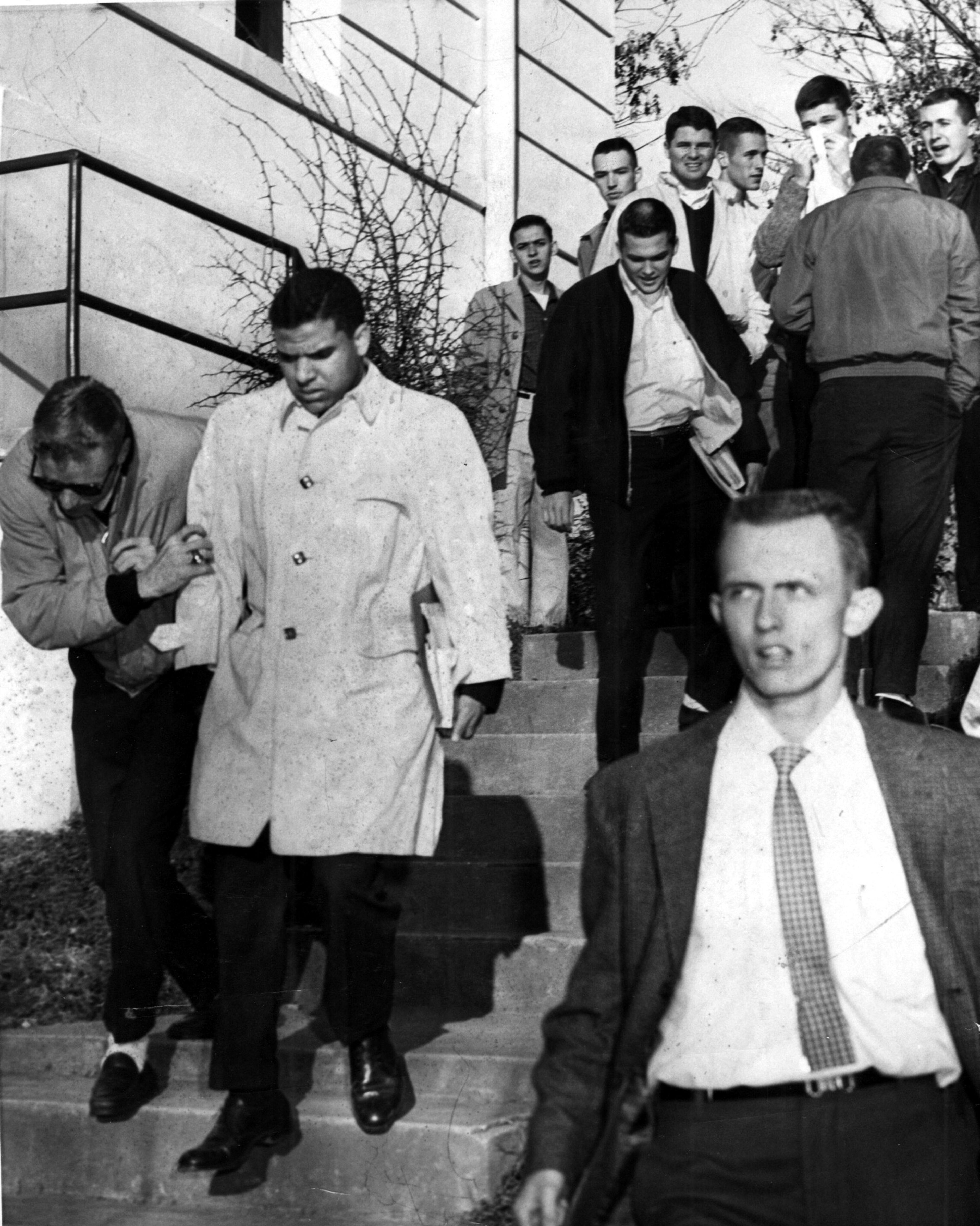

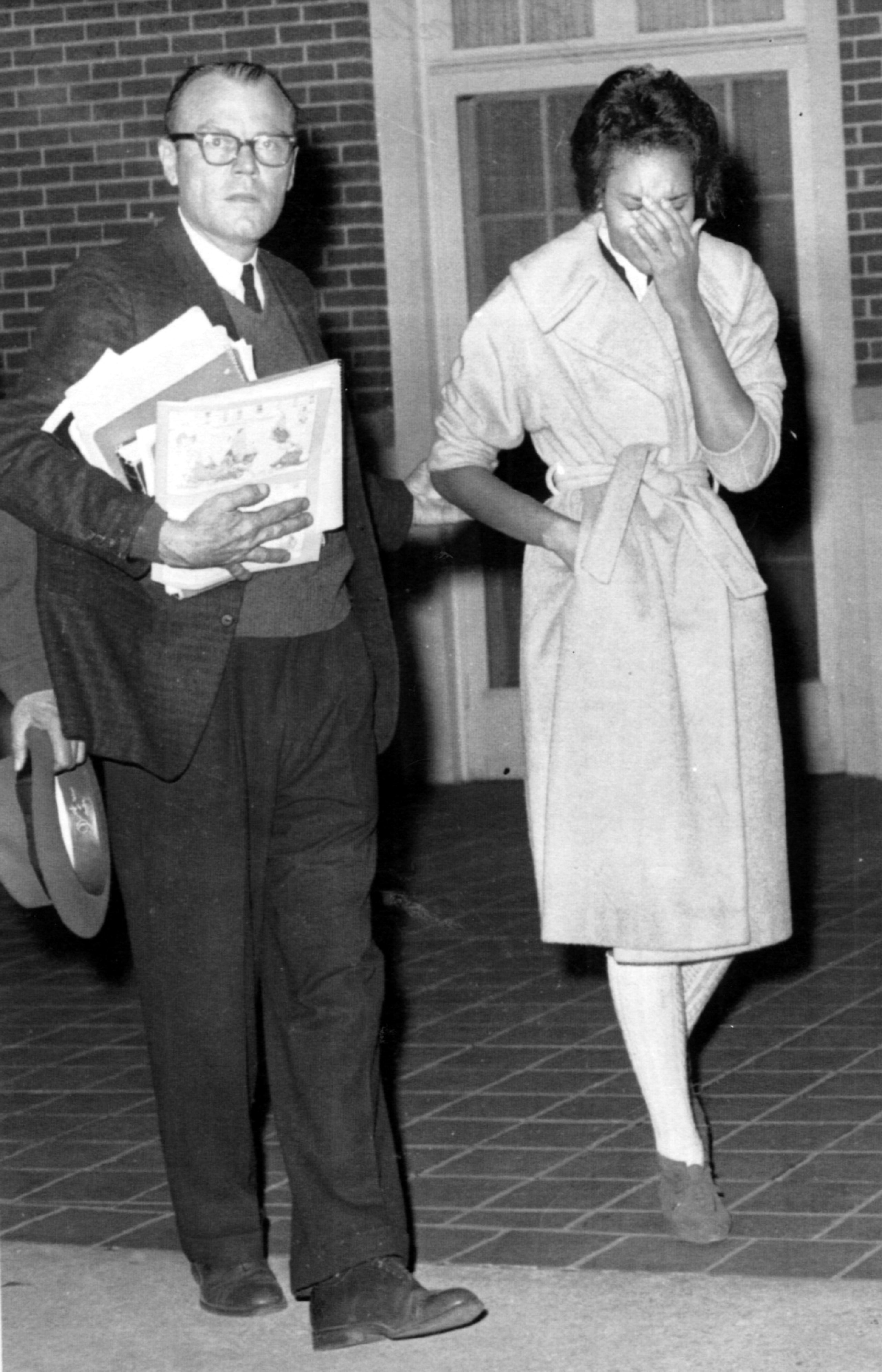

On Jan. 6, 1961, he ordered students Hamilton Holmes Jr. and Charlayne Hunter (now Hunter-Gault) admitted to the University of Georgia, the nation’s oldest state-chartered university. He signed the University of Georgia order following a weeklong trial that pitted the two students against the school’s top ranks.

“Judge Bootle has always been a hero for me, and heroes don’t come every day,” said Hunter-Gault, now bureau chief for CNN in Johannesburg, South Africa. “He was a courageous man who went against his culture, his tradition --- he went against his race --- to do what was right. Somewhere deep inside of him he had a moral core that helped him choose to be on the side of justice. In the process, I think he walked alongside people like Martin Luther King Jr. and stands with the giants of American and Southern history.”

Two years ago, at the time he turned 100, Bootle said: ’'Someone asked me the other day, ‘Wasn’t it hard to make the decision to let blacks in?’ I said it wasn’t hard at all. Once you decide what’s right, the making of it is easy. Right is right.’'

The landmark decision shook Georgia’s segregated establishment. Some people in Macon burned an effigy of the judge. Gov. Ernest Vandiver threatened to cut the university’s budget, though he refused to defy the ruling and soon went along with desegregation.

Controversy never deterred Bootle. He ordered the Bibb Transit Co. to integrate seating on its buses, and ordered several Middle Georgia counties to restore the names of black people removed from voter rolls.

“He’s one of the great judges of our time, in my opinion,” said Frank C. Jones of Macon, a retired partner at King & Spalding who worked with Bootle for 50 years. “He truly believed in equal justice for all. He treated everyone with courtesy and was completely fair and impartial, but didn’t hesitate to issue an opinion that wasn’t popular if he felt it was the right think to do.”

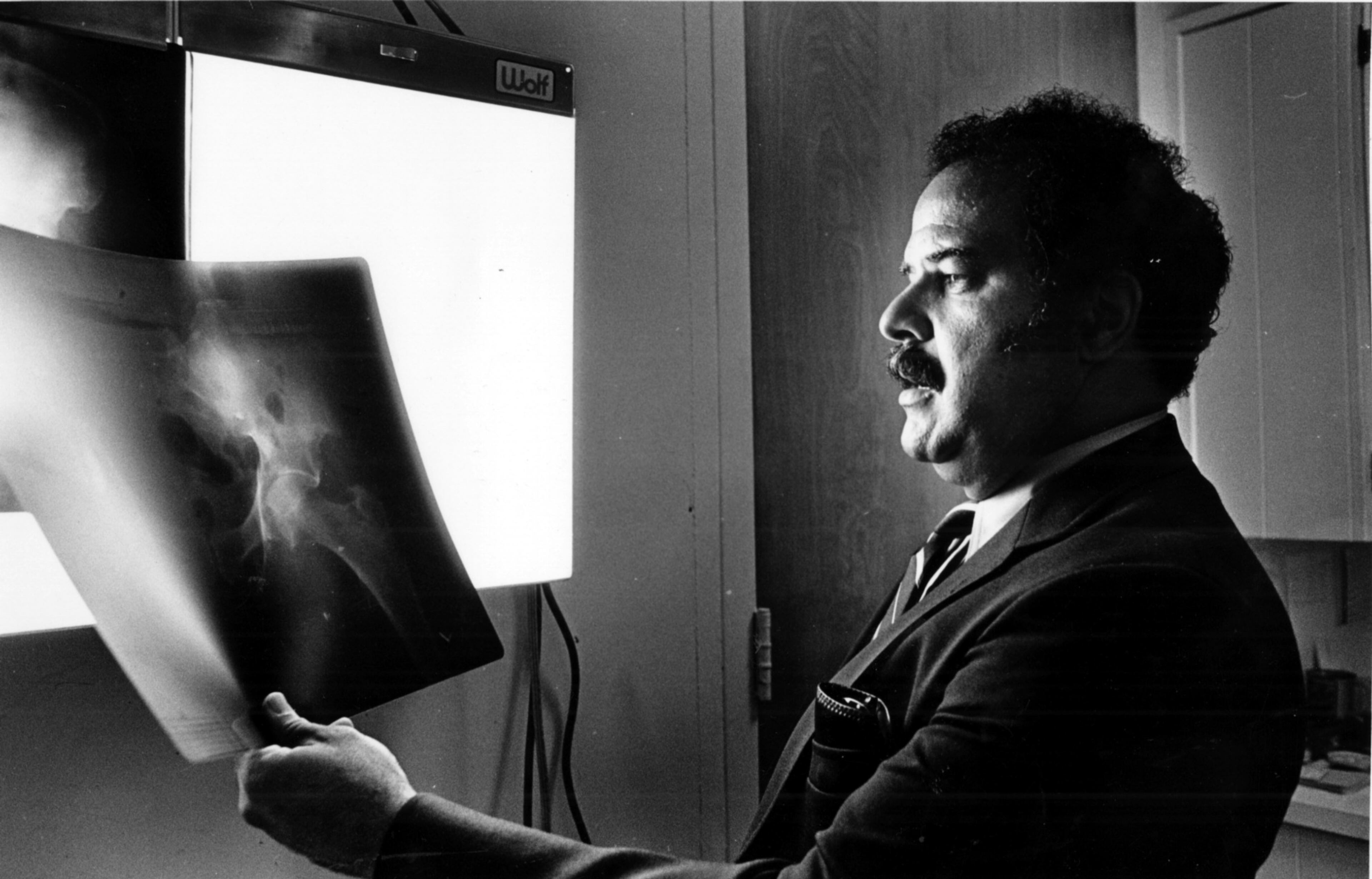

“He was a judicial pioneer,” said Horace T. Ward, a senior judge on the U.S. District Court in Atlanta. Ward, who is black, had unsuccessfully tried to gain admission to the University of Georgia Law School in the 1950s, earned his law degree elsewhere and became a member of the team representing Holmes and Hunter. “Holmes v. Danner was a major decision that set a precedent for what was going to happen in Georgia.”

“Gus” Bootle, as his friends called him, was born in 1902. A Republican and a Baptist deacon, he was a virtual institution in Macon and one of the state’s most respected and experienced jurists. Republican President Calvin Coolidge appointed him a U.S. attorney in 1929.

When the Democrats returned to power with President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933, Bootle lost his job, returned to a Macon law practice and later became interim dean of Mercer Law School --- keeping it afloat for four years during the Depression.

President Dwight Eisenhower named Bootle a judge of the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Georgia in 1954.

Bootle ruled in groundbreaking Georgia voter registration suits. In 1955, he ordered Randolph County officials to reinstate 22 blacks they had arbitrarily struck from the voting rolls.

He integrated Georgia public transportation in 1962. Ending a three-week boycott of Macon city buses, he struck down all state laws, and a Public Service Commission rule, requiring bus segregation.

Bootle retired as senior judge in 1970, but continued presiding over federal cases on a part-time basis until 1981. Macon’s federal courthouse was named for him in 1998.

He made the news again in 2000 when Preston King, a black Albany man he had sentenced in 1961 for evading the draft, was granted a presidential pardon. King had returned from England, where he had lived for 39 years. He and Bootle shook hands in the retired judge’s driveway. “Mr. Preston King,” said Bootle, “welcome to America and to my home.”

The funeral will be 11 a.m. Saturday at First Baptist Church in Macon. Visitation is 6 p.m. Friday at Snow’s Memorial Chapel, Cherry Street.

Survivors include two sons, William Augustus Bootle Jr. of Warner Robins and James C. Bootle of Atlanta; a daughter, Ann Hall of Macon; and eight grandchildren. His wife of more than 70 years, Virginia Childs Bootle, died June 24.

--- The Associated Press contributed to this article.