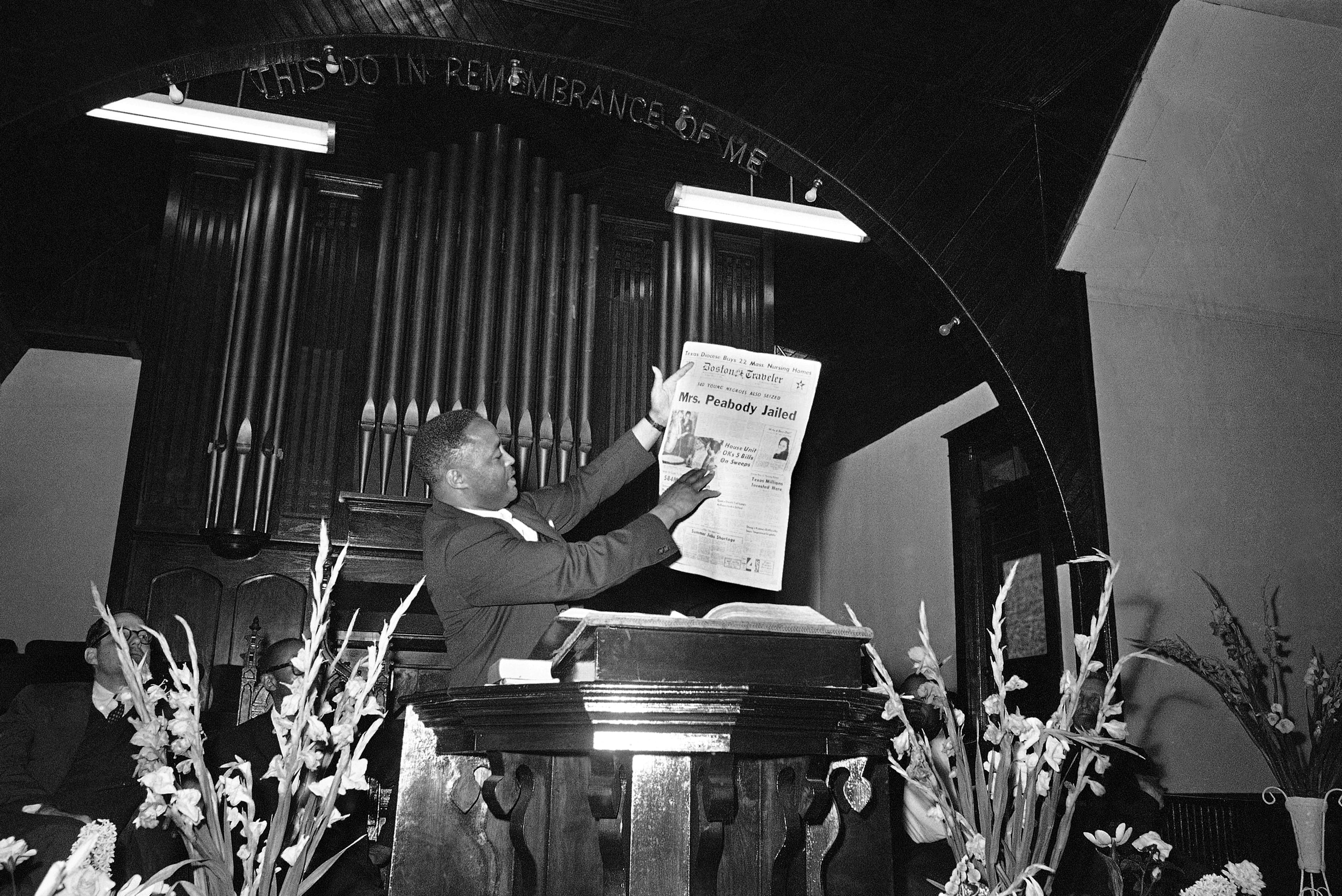

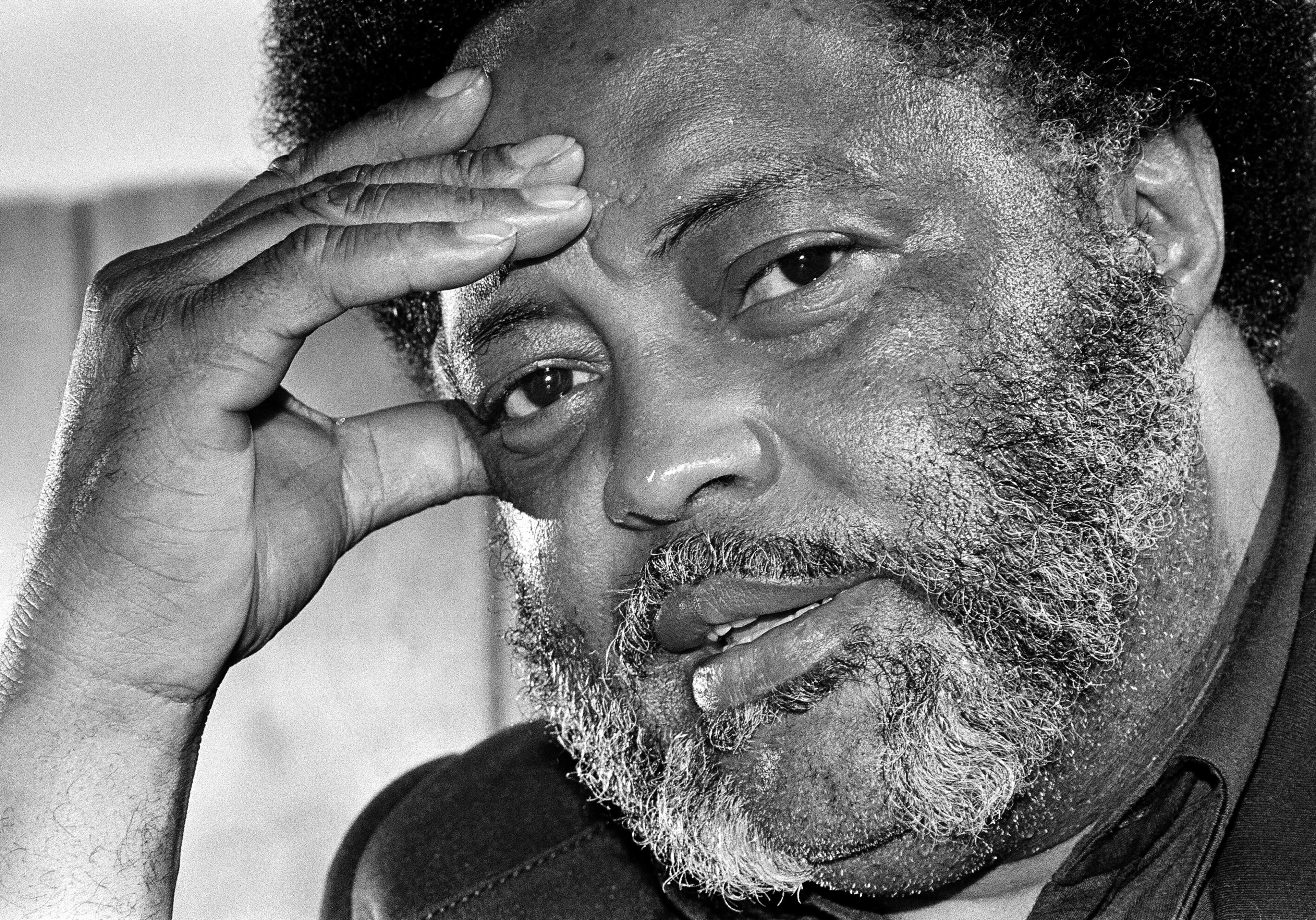

Hosea Williams: 1926-2000 — A lieutenant of the civil rights movement

Hosea Williams marched alongside the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., fed thousands of poor people every year and vowed he was “unbossed and unbought!”

Known for his denim overalls, red shirts and penchant for speaking his mind, Williams was a key figure in Atlanta, becoming a force in local politics, civil rights and the fight against poverty.

Charismatic and controversial, Williams led hundreds of marches as a street-savvy lieutenant in the civil rights movement headed by King. His defining moment was in 1965, when he led the Selma to Montgomery March, which gave momentum to passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

“Hosea made a mark in helping to change America for everybody,” said U.S. Rep. John Lewis of Atlanta. “Hosea is more than one of the foot soldiers. He was brave, courageous and a daring individual, who had little or no fear.” Williams died Thursday, Nov. 16, 2000 at age 74.

Some of the fearlessness may have grown out of difficult family circumstances that molded his self-sufficiency.

In 1925, his mother ran away from a school for the blind in Macon when she became pregnant with Williams, who was born Jan. 5, 1926. His mother died giving birth to another child, Teresa, leaving the two children in the care of their grandparents, Turner and Lela Williams in Attapulgus.

The young Williams stayed with his grandparents until he was 13, before turning into a self-described “thug and gangster,” and working as a dishwasher, janitor, farmer and, according to his own biographical sketch, a gambler.

In 1942, at the age of 16, he lied about his age to get into the Army. He served four years in Gen. George Patton’s 3rd Army as a weapons carrier during World War II and suffered extensive leg injuries in Germany when a Nazi bomb went off in his foxhole, killing everybody except him. Williams lay in the foxhole overnight, clinging to life. When help did arrive, Williams narrowly escaped death when the truck transporting him to a hospital was ambushed and everyone else in it was killed. He spent 13 months in a British hospital and was released as a disabled veteran. He would walk with a cane for the rest of his life.

Upon returning to the United States, Williams, wearing his Purple Heart, quickly learned that the freedom slogans driving the U.S. war effort weren’t being heard in the same way in the South. When the Greyhound bus to Attapulgus stopped at a segregated bus station in Americus, Williams tried to drink from the only water fountain in the station.

A group of white men beat him so badly that they left him for dead and called the black undertaker. The undertaker took him to the Veterans Administration hospital, where he stayed for eight weeks “crying, cause I had fought on the wrong side,” he would say later.

It was a defining moment.

“You can get scared and run, want to get up and kill somebody, or come up with a better way to overcome things, which is what he did,” said civil rights veteran C.T. Vivian. “His courage was amazing, and he never let things get in his way.”

When Williams finally got to Attapulgus, he finished high school at the age 21 in 1947 and enrolled in Morris Brown College, where he received his degree in chemistry, before getting a master’s at Atlanta University.

After graduating, Williams worked for the post office, then as a chemist with the U.S. Department of Agriculture in Savannah in 1952. He described himself at that time as an “upper-middle-class Negro,” whose wife, Juanita Terry Williams, wore furs. She died in August.

Although he was working for the government, in Williams’ eyes it was an unjust government --- especially in its treatment of black people.

But it would take another defining moment to turn Hosea Williams the chemist into Hosea Williams the civil rights activist.

It happened in Savannah the day he found himself explaining to his children why they couldn’t spin on the stools at a drugstore lunch counter.

“I started crying because I realized I couldn’t tell them the truth,” Williams recounted in the Howell Raines book “My Soul Is Rested.” “The truth was, they were black, and they didn’t allow black people to use those lunch counters. So I picked the two kids up and went back to the car, and I guess I made them a promise I’d bring them back someday.”

The moment foreshadowed what would become decades of leading people, at first involving sit-ins and marches in Savannah. He once was jailed for 35 days and lived only on bread and water.

In 1963, his efforts in Savannah caught the attention of King and other leaders of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and they convinced Williams to join them in Atlanta.

“In the 1964-1965 time frame, Hosea was as valuable as anyone in SCLC to Dr. King because of his courage and willingness to lead dangerous demonstrations,” said David Garrow, an Emory University historian and author of “Bearing the Cross,” a history of King and the SCLC. “People may remember Andy Young and John Lewis, but . . . Hosea was just as important to the movement.”

As one of King’s top lieutenants, Williams served as the Ying to Andrew Young’s Yang. “Dr. King would send Hosea Williams to a town to organize it, to mobilize it, to pack the jails, if necessary,” said state Rep. Tyrone Brooks (D-Atlanta), who was recruited by Williams to join the SCLC in 1967. “Then he (King) would pull Hosea out after a while and send Andy to negotiate.”

As one of SCLC’s chief organizers, Williams planned and led several voter registration drives and key marches, including the touchstone march of the movement, the Selma to Montgomery March. He and John Lewis were the first to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge outside Selma, Ala., on March 7, 1965, a day that became known as “Bloody Sunday.”

“In 1965, Hosea was the masterful organizer,” said Lewis, about the 54-mile march. “He was the genius. He was steadfast and determined.”

Lewis said that as he and Williams reached the apex of the Edmond Pettus Bridge, all they could see was a sea of blue --- the Alabama State Police.

“Hosea looked over to me and asked me if I could swim,” remembers Lewis. “I told him no.”

Once they crossed the bridge, the marchers were given three minutes to leave. Williams asked if they had time to pray and within a minute, they were beaten. The beatings, televised across America, galvanized the nation and pressured Congress that summer to pass the Voting Rights Act, which guaranteed the right to vote regardless of race.

Three years later, on April 4, 1968, Williams was with King when King was assassinated on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis. They had traveled to Memphis with several other civil rights leaders to support striking sanitation workers.

Williams remained with the SCLC after King’s death, working with the Rev. Ralph Abernathy and the Rev. Joseph Lowery, and was the national mobilizer for the SCLC’s Poor People Campaign in 1968.

Williams was the executive director of the SCLC when Lowery was president. Williams has said Lowery wanted him to fire the field crew, which Williams refused to do, so Lowery fired him in 1977.

By his own account, Williams was arrested more than 135 times for civil rights in the ‘50s, ‘60s and ‘70s. But over the last 20 years, Williams was jailed about a half dozen times for a number of offenses, including several drunk driving charges. He had more than 30 traffic violations over the years.

A 1981 misdemeanor conviction for leaving the scene of an accident resulted in a six-month stay at the DeKalb County Jail, during which he was re-elected to the Georgia General Assembly. In 1988, he tried to board an airplane with a handgun in his briefcase. In 1992, Williams spent 30 days in jail and 30 days in an alcohol rehabilitation center following a 1991 hit-and-run accident.

“If we think back on the 1970s and 1980s, his driving problems hurt his credibility, especially around Atlanta,” said Garrow. “But all of that is small, considering his contribution in the 1960s.”

To his credit, Williams said while admitting his mistakes, he has never wavered in the quest for civil rights: “I’ve never done anything that would hurt the struggle of black folks to be free.”

In the 1970s, Williams turned his attention to Atlanta politics. He was state legislator for the 54th district from 1974 until 1985. In 1986, he represented Atlanta’s District 5 as a city councilman before becoming a DeKalb County commissioner from 1991 to 1994.

Despite his forays into politics, including a failed bid for Atlanta mayor in 1989, Williams remained an activist.

He led 30,000 people through Forsyth County in 1987 to protest harassment and intimidation of blacks in the county in what would be the largest civil rights demonstration in the South since the 1960s.

His activism went beyond civil rights.

In 1970, Rev. Williams started Hosea’s Feed the Hungry and Homeless Thanksgiving Day dinners at Wheat Street Baptist Church, where he, his wife and a handful of volunteers cooked for 200 poor people.

“In all the 30 years since Dr. King’s death, Hosea Williams remained spiritually and emotionally loyal to Dr. King’s teaching,” Garrow said. “He never went into corporate consulting or anything that has been personally remunerative.”

Now, more than 3,000 volunteers serve more than 30,000 meals annually at Turner Field. In 1999, the 30th year of the dinners, Williams wasn’t able to serve food to Atlanta’s hungry because he was still weak from an the removal of his cancerous kidney the month before the holiday event.

Instead, Gov. Roy Barnes and his wife, Marie Barnes, were among many on hand to serve them, and they have volunteered to so the same this year.

Before every holiday, Williams complained that he didn’t have enough money to feed people and in 1999, he reported that the program was $80,000 in debt. In 1989, 1992 and 1999, Williams reported that thieves broke into storage facilities and stole food and cash.

In 1992, Williams went to the wire looking for a place to hold his annual Thanksgiving dinner, and in 1993 he fought with Atlanta school board officials over using school facilities to dish out a feast on Martin Luther King Jr. Day.

Even in his illness, there were some events that Rev. Williams would not let pass.

He offered support to Ralph David Abernathy III, who was sentenced earlier this year to 10 years in prison for stealing $5,700 through false expense vouchers while a state senator. Williams spoke out against the Coca-Cola Co. when minority employees accused the Atlanta-based soft drink giant of discrimination.

It wasn’t until August, when doctors removed a cancerous kidney, that Williams stepped out of the spotlight.

Williams was founder and CEO of the Southeastern Chemical Manufacturing and Distribution Corp. He was a member of Phi Beta Sigma, National Order of Elks and Free Accepted Masons; Veterans of Foreign Wars; Disabled American Veterans and the American Legion.

Learn more

2019: Hosea Williams’ dream of helping homeless lives on

2020: The King Generation is nearly gone; who is stepping up?

Photos: The legacy of Hosea Williams

2016: Civil rights icon’s daughter makes sure his work to help poor lives on

2021: Now called Hosea Helps, the organization that Williams founded now has a home of its own